ICHNOLOGY-the

study of animal traces (tracks, burrows, etc.) Page 3

This page was born 06/12/2023. Rickubis designed

it. (split it off from an older page.) Last update: 02/21/2025

Images and contents on this

page copyright ©2001-2023 Richard M. Dashnau

Go to

Ichnology page 2

Go to

Ichnology page 1

Go to

Ichnology

page 4 (this has the most recent observations).

Go back to my home page, Welcome to rickubis.com

Go back to

the RICKUBISCAM

page.

----------------------------------

That's me on the 40-Acre Lake Trail at Brazos Bend

State Park (12/31/2007). I was waiting for an otter to show up.

It didn't.

Over the

years that I've been keeping these pages,

making new observations and learning new things, I have met

some interesting people.

Two

of them are Dr. Anthony Martin and Dr. Lisa Buckley.

They study ichnology--

animal traces. While the term is commonly used in

relation to fossils (such as dinosaur tracks), it also applies

to living creatures as well (sometimes called "neoichnology"

with "paleoichnology" for fossils). One major

aspect of this study is that such traces can show animal behavior. For

instance, a single footprint might not say much, except

what kind of animal made it; but a series them might tell

if the animal was running, or jumping etc. There are

three basic factors that help to interpret traces: A)

Substrate (the

material that holds the trace) ; B) Anatomy (the part of the

animal that affected the substrate) and C) Behavior (what the

animal was doing with the anatomy that affected the

substrate). (see "The Three Pillars of Ichnologic

Wisdom" page 9 in Life Traces of the Georgia Coast by

Anthony J. Martin) I admit that I am not very good at

finding and

interpreting such traces. But, it is still fun to look and try

to piece together the mystery of what transpired at that spot

before I got there. I usually capture images of animals

activity. But every now and then I've taken pictures of

traces. I'll begin collecting them here. I will

eventually arrange them in chronogical order of some kind.

Many, many

thanks to Dr. Martin and Dr. Buckley for many conversations

via email and online; and for being supportive of my

amateurish efforts.

One more

thing: Although alligator burrows (or dens) and nests would be

considered ichnological traces. I've only got one example of

an alligator den on this page. I have

many observations of alligator dens, and have already gathered

them onto other pages, starting here.

This

page is arranged with the newest entries at the top.

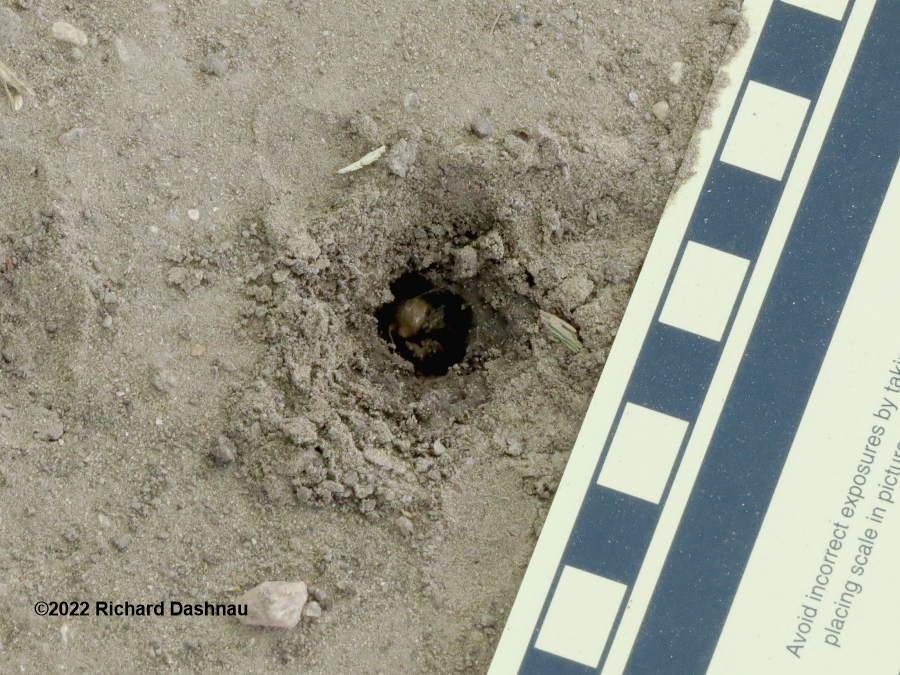

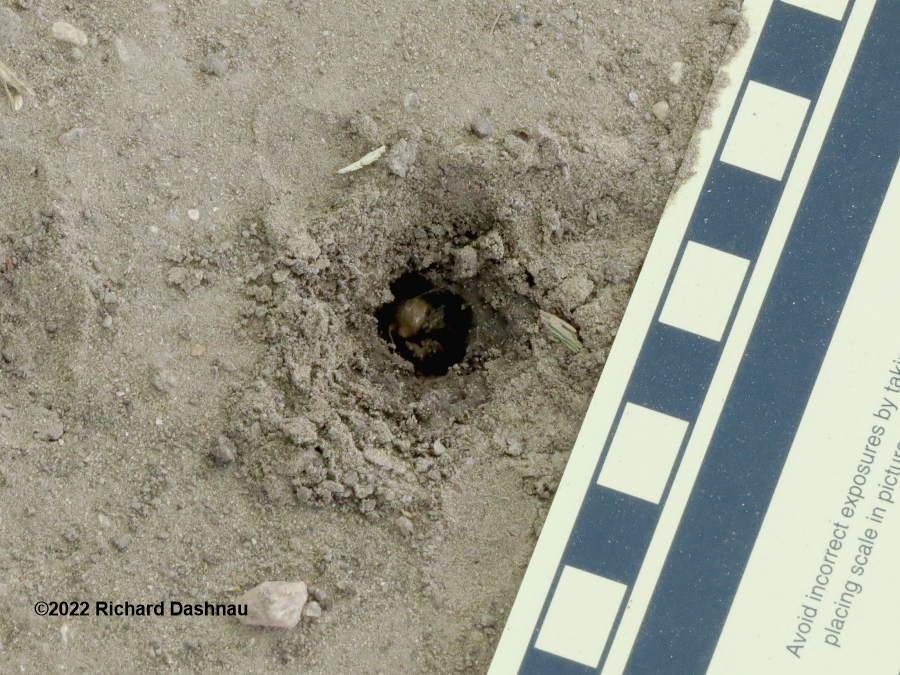

05/27/2023 I went to Scobee Field to

see what the rain a few weeks before might have affected. The area

was mostly dry, although there was a little bit of

water in the ditches near the road. I examined the dried ditches

to see what sort of burrows were left, and I found another example

of an Apple Snail in a burrow! Although

they live in water, Apple Snails can aestivate in mud during dry

periods for 10 months! For more about Apple Snails (Pomacea sp.)

you can visit my snail page here.

There were a few egg masses on the culvert near the restrooms even

though the ditch was dry. So I knew that adult snails had been

around. Then I saw this hole that

contained 2 snail shells.

I

used a metal rod I'd found in the area to measure the depth to the

top of the snail shell--about 5 centimeters. When worked the snail

out of the hole (it was a tight fit), I

found that the snail was alive. The operculum was sealed across

the shell opening and was being held tightly closed. I was

taking pictures with my phone, and in the

bright sunlight it was hard to focus into the hole. But I got a

few, that show the bottom was rounded across the width, and pretty

smooth. How does an Apple Snail dig,

anyway? Of course, the hole was dug while the bottom was still

soft, as the water was evaporating. The snail was about

5cm...long?

The hole was

about 5-1/2 cm across (of course, snail sized). I used the same

rod to measure the depth of the hole--about 9cm! I still can't

find any images of Apple Snail

burrows anywhere online (although I can find mention that they do

burrow to aestivate). This is my second direct observation of an

Apple Snail in a burrow. The first one

was also at Scobee Field, and is shown on my my snail

page here , as well as one of my ichnology

(animal

traces) pages here.

On

01/08/2023 I was at BBSP, and it was

an interesting day. It had been raining at the park. Many

of the trails are covered with a crushed-stone material.

When we get

the correct type of rain, water collects on the trails,

and the lighter materials in the trail-the tiniest

grains-work out and then settle on the low spots. This

leaves sections of fine-grained mud that

are good for collecting footprints. The best time to

see footprints on the trails in BBSP is early morning.

There are two reasons for this: 1) When the sun is

low, the light makes such traces

easier to see. 2) Most footprints on the trails are

obliterated by traffic by the end of the day. There were

two sets of alligator tracks that morning. The first set

was from a larger gator and shows

the big four-toed rear feet, the smaller front feet, and a

good crease made by dragging the tail.

Another

set was from a smaller gator and shows a fainter trail,

but with some scale impressions captured in the

footprints.

There were also these

mammal tracks. I always hope see Otter tracks, but I don't think an

Otter made these. No traces of claws or webbing, for one thing.

They are too big, and the wrong

shape for a Squirrels or Opossum. They aren't right for Nutria either.

Raccoons have a very clear "hand print" shape, so not that,

either. Armadillos might walk the trail, but I usually don't see

traces of them on the Spillway Trail. Also, Armadillos tend to bulldoze

through plant matter on the edges of the trails, and I didn't see any

evidence of that. Dog prints are more stretched

front-to-back, and usually show toenails, so I don't think they're

from a dog. The prints have a more "oval" shape, longer

side-to-side, with large middle pad. The front feet are slightly more

stretched. I believe these are cat prints...and a pretty large one,

since the prints are about 2 inches across. Maybe a bobcat made

them!

There were 2 sets

of prints at least 20 yards apart. This is the second set. The

prints are the same shape and size as in the first set. If they did come

from a Bobcat, then I might have just

missed seeing one walking along the Spillway Trail.

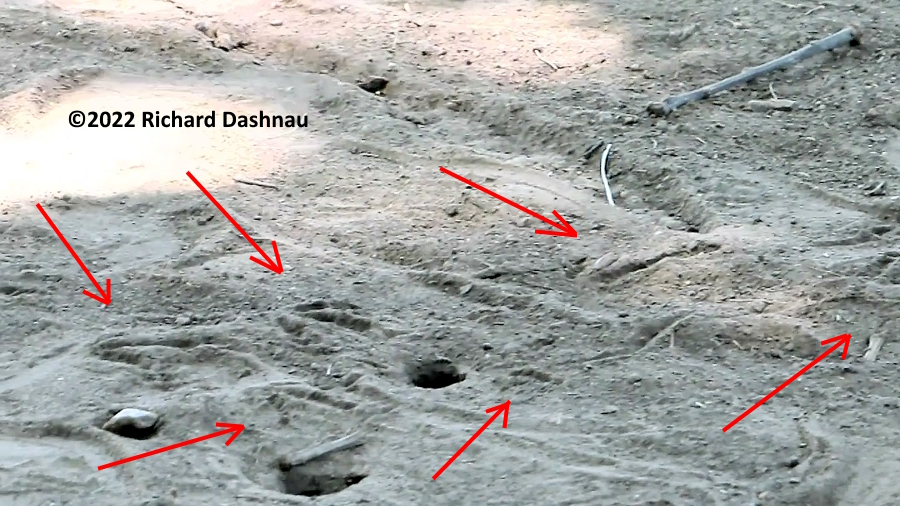

From BBSP on

07/03/2022

The water level drop in Pilant Lake has affected all kinds of

things. I've been curious about watching Gallinules using

their long toes to distribute their weight over

various substrates. On 7/03, I was able to get a close look at

Gallinule walking on the mud in Pilant Lake. The video

of this one walking, and the others chasing the Little Blue

Heron are in a video

and the video is here(mp4). The

images

below (and above) are frames from the video. The

video shows how resilient the mud surface was, as it flexed

and sprung back as the bird

walked on it. There were some footprints left, but only

faint ones, that probably would fade. Then, the Gallinule

stepped into softer mud, and it ran off, using the same

technique it would

use to run on water--flapping wings and running. That time it

left impressions, but the mud was too soft for them to last.

The arrows in the images point to the footprints.

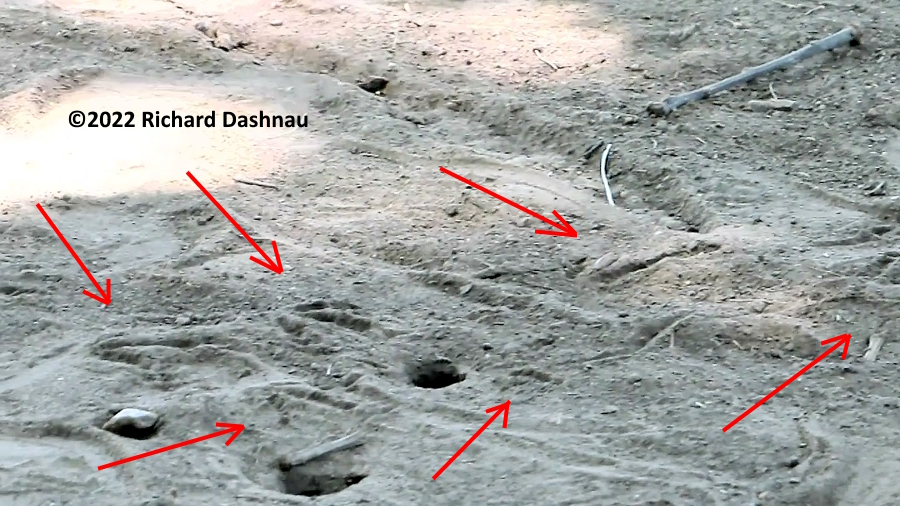

(added 2/21/2025) In

Houston on 05/18/2022

I'd seen Great-Tailed Grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus) hunting

cicada nymphs in this area, and had seen them digging into the

burrows by pulling up the caps. On this day, I shot some

video of a Grackle eating a nymph there, and that's shown on

this page. Afterwards, I shot very short video of a

Grackle

walking through the dirt. I tried to capture the formation of

footprints. The images below are frames from the video.

The arrows show the new footprints.

The Grackle walked past an old

burrow. Since the hole was intact, it showed the Nymph had

emerged a while ago, and had not been dug out by a predator.

The last image shows

more of the new traces, marked by arrows. The short video is here.

In Houston on 05/11/2022

At my exercise area, I noticed another mud "cast" on the dirt

trail. This time, I thought I knew what it was (because of

what I'd seen a week

ago), so I got the camera before investigating. I pulled

up on the "plug" and uncovered another cicada nymph burrow. Click

the

link for a short film that includes some of these photos

as well as some video clips.

About 5 minutes later, a cicada

nymph showed its face, and started

applying a paste to the edges of its hole. As with the

previous nymph, this one withdrew, then returned a few minutes

later to add more paste to the edge of the hole. I replaced

the plug

and left something near it so I wouldn't step on it, and

started my exercises.

This is the second time I've

seen a cicada nymph produce "paste". I figure that it's

partially-composed of dirt; but what is the moistening agent?

The ground was dry, and I don't think there

was "mud" just a few inches down. Do the nymphs secrete

liquid? If they do, what is it--water, mucus...something

else? How much can a nymph produce?

From

Houston on 05/02/2022.

I was checking my exercise area for stones and poop when I

noticed this lump. I didn't want to step on it for many

reasons. I could

already tell that it wasn't poop, but thought it was a

burrow casting of some kind. When I picked up the lump,

what I uncovered was so interesting that I put lump back, then

delayed my

exercise to run back to the car and get a camera. Then I

lifted the mud lump again. The hole looked like a cicada

burrow (I often see them here). But the fabricated mud cap had

confused me...

...until the owner of the

burrow appeared.

It was a cicada nymph! Then it returned to the depths.

By the way, the images of the nymph below are from video

I filmed then. You

can see the

short video here (mp4).

I waited a while, and it made

another trip. I've seen many cicada burrows-here, and at

other places. But this behavior was new to me, so I did

research after I got back home. Cicada

nymphs sometimes make a chimney, turret or a cap

over their burrow while waiting to emerge! I saw

pictures online of some turrets that resembled small versions

of crawfish chimneys.

Type "cicada chimneys" or "cicada turrets" into your favorite

image search and you'll see what I mean. This really

surprised me. I'd just assumed that the nymphs came out of the

ground

when they are ready to do their final molt, climbed up, and

did their final "pop". But apparently sometimes they "wake up

early", hit a snooze button and go back underground for a

while.

I was also reminded by many references to how Copperheads like

to hunt for emerging cicadas--and possible increase in numbers

of Copperheads during Cicada emergent times.

This is the underside of the cap that I removed. It was hollow

on the bottom. I put the cap back over the hole. Note how

dry the dirt is--the cap had not been"glued" to the loose dirt

.

I put my tripod over the hole so I wouldn't disturb it

further when I resumed my exercises.

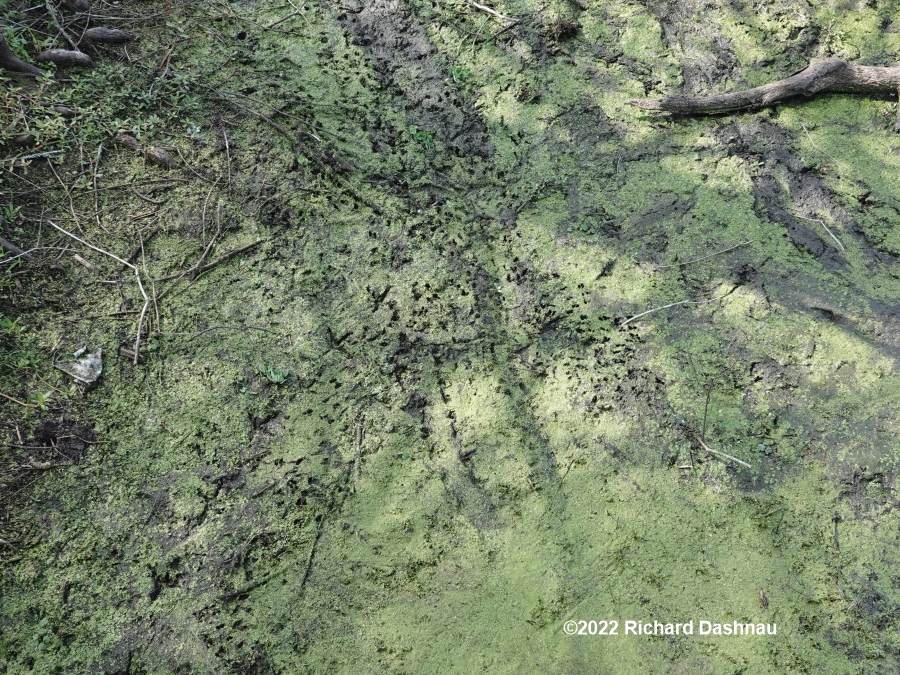

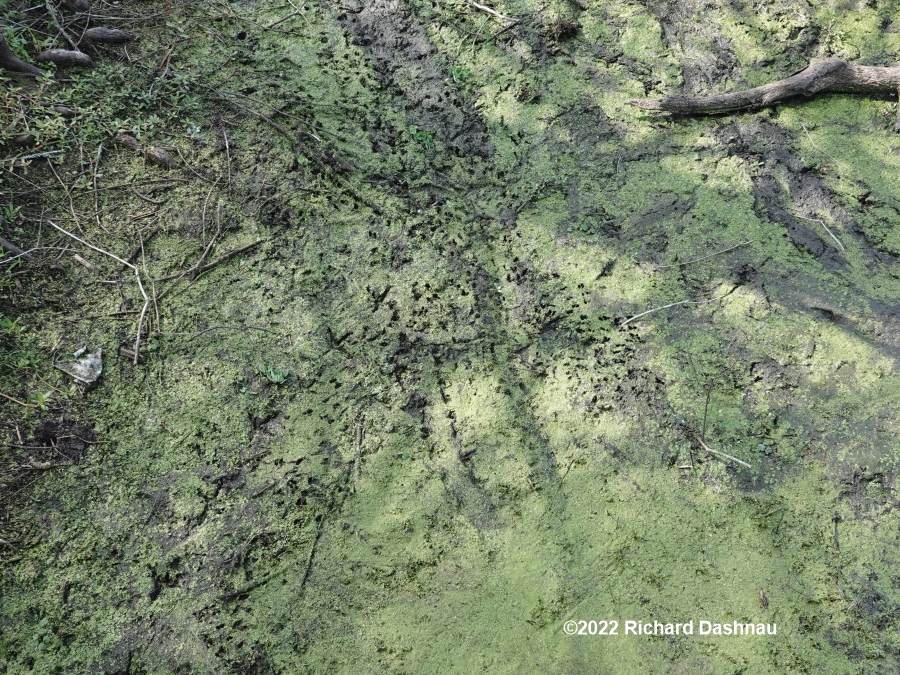

From BBSP on 04/10/2022.

I was leading the Creekfield Hike when we got to the small

bridge. The lake has been very, very shallow lately. When I

looked over the

bridge rail while interpreting for the hike, I was a bit

saddened by seeing the expanse of mud on the West side. But

then I noticed all of the footprints and marks in the mud near

the bridge,

and became very excited. I gave the hike members a brief

description of Ichnology--the study of animal traces. Then

we spent few minutes looking at the animal traces in the

mud, and

trying to figure out what had gone by. The Creekfield hike

isn't normally defined by strict time limit, but I had

signed up for another task in an hour, so I had to move

the hike along. But we

had some fun anyway...and we encountered more tracks by

the pier--and I forgot to take pictures of those. I now have a page dedicated to Ichnology, but

I'll summarize here: While observing

animals as they act, we can learn about their behavior.

But as animals move through the environment, they can

effect it--by leaving footprints, scrapes, burrows, poop,

etc. These traces can

also be clues to animal behavior. One footprint by

itself can give some hints about what made it; but a

series of footprints can show if the animal was running,

hopping, or where it went.

Following a track in either direction lead to a burrow, or

to remains of what it left, etc. So, here are a

couple sets of photos from the bridge.

The

first

set is actually 3 zoomed views of the same spot. In the

first, the big, curved track is obvious. Theres a set of

tracks crossing that one. But in the closest view, we

can see a lot of

traffic and activity. I can try and guess what made

some of the tracks. Although the thick track was pretty big

(maybe 5 inches across at least), I know it wasn't an

alligator, because the feet are

round (no prominant toes) and the steps are too close

together; and there's no tail drag mark. That looks

like a big turtle walked out and moved "up" in the picture.

Turtles take very short steps,

have short toes, and I think the bottom of its shell

dragged across the mud because its feet sunk into the mud.

The large bird that crossed from left to right was not

a duck (no webbing),

or a coot (narrow toes); but probably a heron or egret, or

ibis; because 1 long thin toe pointing backwards. I

think the "splattery" marks were just made by stones tossed

into the mud.

Then I took

these pictures just a bit too the left of the first one. The

left end of that stick show in them. I noticed all the small

holes around the tracks. And I think that those are marks

made by the birds

beaks as they probed the mud. I could not get closer to the

tracks to place anything for scale, and the lighting wasn't

good enough for better zoom shots. Still, the marks

seem to be arragned in pairs,

probably from upper and lower beak being pushed into the

mud. Also, this added observation may help identify at least

on of the trackmakers as an Ibis. Ibises spend most of

their foraging time

stabbing their downward-bent beaks into water and mud. Other

birds also probe, but I suspect this was an Ibis. There are

also at least 3 other "tractor-style" traces. One is large,

like the in the photos

above, but two are smaller (maybe 3 inches across).

The prints are also close together, and I suspect they

were smaller turtles. Look at the pictures, and

imagine how those traces came to be in

the mud. Birds walking (not hopping-by the way-another

clue), probing the mud; while turtles waddle through.

Figuring out such signs can be very interesting and

entertaining.

Here's

something that appeared on 40-Acre Lake trail on 10/10/2021.

Yes, it's feces, poop, scat, or stool. At first thought,

it is just evidence that an animal left a "sculpture" on the

trail.

But, this

sculpture was left by an alligator. Since most people

aren't lucky enough to move around in alligator habitat; most

people don't get to see this. Usually, I have to identify

the scat by size, color, texture, etc.. But this

sculpture was signed by the "artist"! That squiggle on the

trail leading to it(or from it) is a drag mark left by the

alligator's tail.

Go to

Ichnology page 2

Go to

Ichnology page 1

Go to

Ichnology

page 4 (this has the most recent observations).

Go

back to my home page, Welcome

to

rickubis.com

Go

back to the RICKUBISCAM

page.