This page was born 09/28/2021. Rickubis designed it. (such as it is.) Last update: 2/4/2025

Images and contents on this page copyright ©2021- 2025 Richard M. Dashnau

Go to Welcome to Rickubis.com for links to my other pages.

Go back to my RICKUBISCAM page

Today is 9/28/2021. I hadn't known anything about Apple Snails before July of this year. Since then, I've read a lot about them, found them, filmed them, and tried to help

control them. I quickly gathered a lot of imagery and information about them, so...here it is. For now, the newest material is at THE BOTTOM of the page. This shows

how my knowledge of these snails has changed over time.

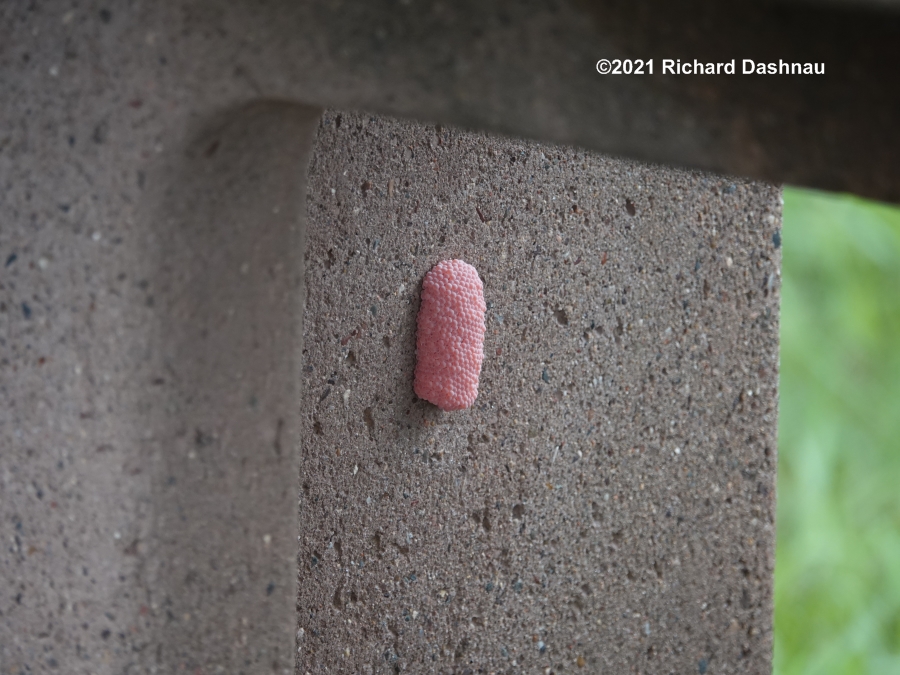

07/08/2021 - 07/10/2021 A friend of mine told me about seeing Apple Snail egg clusters along the Live Oak Trail at BBSP. He also mentioned that Limpkins had appeared in the area--

since they are known to eat adult apple snails. I'd only recently learned that the egg masses of Apple Snails look like wads of pink bubble gum stuck on surfaces near water, because I'd

seen one mass on a tree in Houston, at Fiorenza park. Just *one* mass, and at the time I didn't know what it was. I haven't seen any there since. But, about a week ago, I noticed a few egg

masses at Scobee field, but hadn't thought much about how they got there and what they meant. But then I started reading about them. And I went back to Scobee for another look, and took

the pictures here. At some time recently, most of that park must have been flooded. This makes sense because that entire area is *inside* the Barker Reservoir-a flood-control structure

which is designed to capture water. Anyway, I went there between bouts of rain, so didn't have a lot of time this trip. The pictures are all of the same area. Note where the eggs are. The

masses on the "bridges" over the ditch aren't a big surprise (there's water in the ditch) but then there are masses on the tree, and on the picnic table. Water must have been higher. I didn't

see any snails this trip. Also, I dealt with all the egg clusters I took pictures of (and more that I didn't get pictures of).

Egg Aftermath

Then I did more research. The source I liked best--which seemed relevant to Texas was this one: Identity, reproductive potential, distribution, ecology and management of invasive Pomacea

maculata in the southern United States (by Romi L. Burks et.al. 2017). This book was also very informative:

Biology and Management of Invasive Apple Snails ed. Ravindra C. Joshi, Robert H. Cowie, Leocadio S. Sebastian 2017. It also contains the prevous study. I found the book in many places

online. Here's one link: https://enaca.org/?id=931

This is what I've learned. The term "Apple Snail" is too general. Over time, it has led to some confusion while discussing these animals. In the Southern U.S., the species Pomacea maculata is

the most widespread. P. maculata were probably introduced here through mishandling of the snail by aquarium owners. The snails can keep enough air in their shell to allow them to float. Then,

if the body of water they are living in became flooded (like in a hurricane. Harvey, for instance.) the water can carry them everywhere and anywhere. Perhaps that's how they got to Scobee field.

P. maculata lay eggs on surfaces above the water line, usually during dawn and dusk. A normal clutch of eggs is about 1500-2100 and takes about 30 minutes to deposit. The eggs hatch in

about 2 weeks, and can yield hundreds of hatchlings. The best hatching results if the eggs remain dry for 6 - 9 days. Any submergence during this time can affect the stability of the eggs. The

eggs are also toxic, possibly a by-product of the same chemistry that allows them to incubate in open air. Their bright pink color may also serve as a warning against being eaten.

P. maculata apparently eats almost everything. Like many snails, P. maculata eats periphyton (algae, detritus, etc. that cling to surfaces); but they also eat macrophytes (larger plants that are

visible all the time...duckweed, rice, lotus). In Louisiana, they are of major concern for rice farmers, as the snails will eat young plants. The snails will also eat crawfish eggs. Although the eggs

are toxic, the newly-hatched snails are fair game. It's possible the young snails could be eaten while they're growing by the predators that are usually around--crustaceans, insects, fish, turtles,

wading birds and some mammals. Some crawfish species seem to prefer P. maculata hatchlings to those of native snails. The birds called Limpkins don't normally live in Texas, but some have

recently been observed here eating Apple Snails!!

One more thing--P. maculata-like many snails-are inhabited by many parasites. Some of these are dangerous to humans. One worm in particular--Angiostrongylus cantonensis (aka Rat

Lungworm) is pretty nasty. It is generally spread to humans when they eat improperly-cooked snails. The book I mentioned above gives a very good view of how many countries are trying to

control the damage being done by the various species of "Apple Snails". The studies are good examples of what major incursions of the snails look like. They look BAD. A common method of

early control is to destroy egg masses whenever they are found, and capturing and disposing of adult snails. In both cases, care should be taken to avoid being contaminated by contact. Also, I

haven't found very much descripton in what do do with snails after they're collected. It is illegal to transport the snails in many places--to prevent further contamination. I suppose crushing them in

place is an option (but not very humane...which might be why it isn't suggested often). I've also seen references to freezing them....for a few days to be sure they're dead. It appears that

P. maculata can also survive short exposures to freezing temperatures.

Now, when I look at my pictures, it seems that there isn't really much at that park there for adult snails to eat. The hatchlings might be able to live off periphyton for a while, but there isn't much else.

And, once the rain stops, those ditches are normally dry over the summer. Between the wading birds coming in to clean out the wet ditches, and lack of water, perhaps the snails who have ended

up at Scobee will mostly die anyway. To be sure, I did make sure to smush all the egg masses I took pictures off--plus more that I didn't.

On 07/10/21, I returned to Scobee Field. I went early, hoping that I could catch a snail laying eggs. And, I did! I shot some pictures of the snail at work, and some video clips as well. If you

examine the pictures below, you'll see how much more water there is. It rained a lot Saturday. The model airplane group that runs Scobee Field were having an activity there, so I didn't stay in

their way (They were perfectly friendly. I just didn't want to be in the way.) There was one snail at work, so I filmed that one. The video is here. I was amazed when I saw how the eggs were

carried out of the snail, and up to the wall. There was a sort-sort of trench in the snail's flesh. But, it wasn't a defined structure. It changed shape, and other dimples formed to carry separate

clumps of eggs. Pictures in the bottom row below show this....trench. The video shows it working.

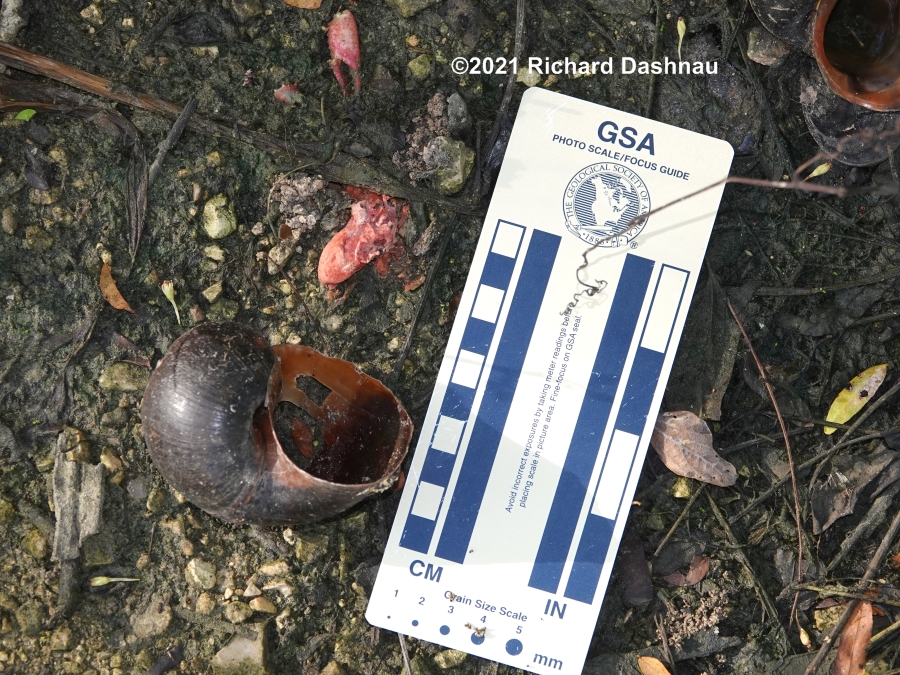

The final picture shows an empty shell that was there. Something had eaten most of the snail out of it. There were lots of wading birds around that morning. One of the folks walking around

suggested that raccoons might eat the snails. That's encouraging, but I have a question (at least one, anyway). Since the eggs are toxic-which prevents most animals from eating them (the bright

pink color might act as a warning (aposematic coloration)); then what happens to animals that eat a snail that has eggs inside? Also, the egg masses I saw, and the snails I found--were

removed carefully. They're gone. Since I always carry hand disninfectant, I used it after this.

Egg channels The shell is not smooth everywhere. Something ate most of this one.

07/25/2021 and 08/01/21- I've been doing more research on our apple snail invaders since July. When I saw the inside of an adult Pomacea, I noticed orange masses or organs. I figured that

those were eggs. Since the deposited egg masses are toxic, I wondered if the eggs inside the snail were also toxic. And, if the eggs are toxic--how can any animals --such as Limpkins--eat the

adult snails? After a lot of searching, I couldn't find any detailed description of how this situation is dealt with. The first picture below was taken on 7/24/21, but I'd seen inside other snails before

then. The other two pictures were taken 7/10/21, and show a snail that something had eaten. At the time, I hadn't realized that the toxic egg masses had been left inside the shell.

I found a number of references saying that animals that eat the snails discard the albumen glands. But the only predator I saw named doing this was Snail Kites. But no clear descriptions.

I started searching for proof that Limpkins might discard these organs. I found a video on youtube that shows a Limpkin doing this! After that, I started looking around BBSP for signs

of this behavior.

But let's pause a bit. Limpkins? Limpkins (Aramus guarauna) are long-necked wading birds with long, pointed beaks. They're about the size of Night Herons (maybe a bit larger).

According to Avibase, the World Bird Database, it is the only extant species in the genus Aramus and the family Aramidae. The "home range" of 4 subspecies of Limpkins is: Florida, Cuba,

Jamaica ; southern Mexico south to western Panama; Hispaniola and Puerto Rico; central and eastern Panama; South America, south west of the Andes to western Ecuador, and east of the

Andes south to northern Argentina. Like many wading birds, Limpkins can be generalist predators but according to many sources, the greatest component of their diet is: Apple Snails. If we

examine the list of regions in their "home range", we can see something missing-- TEXAS. That's right. In fact, their home range is far from Texas.

Texas is now being invaded by Apple Snails. If only Limpkins were in Texas! Well...they ARE in Texas. In fact, they have been hanging around in the lake next door to BBSP for some months now.

That lake is infested with snails. Unfortunately, the snails have made their way to the BBSP side of the fence, along Live Oak Trail. But the Limpkins have been picking them off there, also.

Discarded snail shells litter the trail. I went down Live Oak Trail on 7/18, and I saw something interesting among some discarded shells. I took a few pictures. Next to one

of the shells is a pink mass. I think that mass is one of the "albumen glands" that was discarded by the Limpkin that ate that snail. The trail was really wet, so I didn't go further.

First 3 images below show shells on the trail, and a pink mass neer them. The last image was taken there on 8/1/21, and shows pink material in the discarded shell.

I returned to Live Oak Trail the next week (7/25). I'd been around the other trails, and entered Live Oak from the East end and walked West. I was doing snail egg removal. It was Noon,

and it was hot, so I didn't expect to see anything. A Limpkin appeared on the South side of the trail, near the fence, and hunted the area near the fence. I stayed back, and hardly moved.

It came to the trail, walked on it a bit, then went back under the fence and eventually up the levee and across. I got pictures and a bit of video! This is all edited into this video.

Next weekend (8/01). I'd been out on the other trails first. I met a couple park visitors I'd sent to Live Oak trail and they told me they'd hadn't seen any Limpkins, but had seen snail egg masses,

and even a few live snails. So I was on Live Oak Trail again, at about 12:30pm. I'd gotten almost to one of the "bridges" when I saw a Limpkin up in a tree between the trail and the

road--that is, North of the trail. I watched it for about 20 minutes, until thunder from approaching rain clouds convinced me to start back to my car. I got a brief look at another Limpkin

in a tree near the one I'd been watching. They both moved, and seemed to start hunting, but I didn't want to get caught in rain that seemed to be approaching. I got photos and video

clips. Again, this has all been edited into this video. More information about Limpkins is on my limpkins page.

And, I found another snail shell that seemed to have remnants of a discarded "albumen gland" in it. I also found another paper that seems to have been inspired by the habit of snail predators

discarding the "albumen gland": "Apple Snail Perivitellin Precursor Properties Help Explain Predators’ Feeding Behavior" 2016 by Cadierno, Dreon, Heras. While it discusses Pomacea

canaliculata and not our problem (P. maculata), I think it's still related. This study is where I got the term "albumen gland" for the organ which produces the snail eggs. Perivitellin serves as a

nutrition source for snail embryos (similar function to egg yolk ). While the paper is a bit technical for me to fully understand, for me it verified: a) that the organs are toxic, and therefore

consumption of the entire snail could be dangerous; b) that experienced predators do discard toxic parts of the snail, rendering it safe to eat. From the paper: " Therefore, as the noxious

perivitellin precursors are exclusively confined within the AG, this explains why it is the only usually discarded organ, even when this behavior implies a large loss of the total energy and

nutrients available from the soft-body biomass (Estoy et al. 2002). Finally, we propose that the reddish-pink gland color may contribute to this behavior, helping the visual-hunting predators of

adult snails to associate the bright AG color with the noxious compounds it carries."(page 466 "AG"=albumen gland)

This could be trouble for our local predators (such as alligators) that might consume entire snails. Raccoons might be able to identify and remove the glands, but they'd have to learn about the

danger first (that might be what ate the snail in the picture above). It's potentially good news that Limpkins are eating snails here. It will be better news if they establish a breeding population in

Texas. They can help control the spread of the Pomacea. But, regardless of predation, and it seems to me that the snails will remain. I think the most we can hope for is that the predators that

have followed the snails (and other local predators) and the snails will reach a "balance" where the snails will not overpower the environment. There must be reasons why Limpkins haven't made

the journey here before. If lack of snails was a factor...where they're here now. But, if there are other environmental reasons (such as temperature) the Limpkins may not stay. I hope they do.

My Big Apple Snail Followup, written 09/28/2021-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Update 09/28/21- I made repeat "snail expeditions" to Scobee afterwards. I scraped off egg masses, and on one visit removed 52 snails--and those were moving around in the drying ditches

and trenches. One might think that we could just leave them alone and the snails would eventually dry up and die. After all, they're only snails, right? But these are *really tough* snails. LOL

They have been observed feeding in water at 2deg C . In hot dry weather they can aestivate and can survive easily in 15 - 35 C ( 59 - 95 F) (from: "Identity, reproductive potential, distribution,

ecology and management of invasive Pomacea maculata in the southern United States" by Burks et. al. Page 305)

Oh...and this species has a gill and a LUNG. An actual, vascularized lung--which allows them to breathe while out of the water.

From: "Comparing apples with apples: clarifying the identities of two highly invasive Neotropical Ampullariidae (Caenogastropoda))" by KENNETH A. HAYES, ROBERT H. COWIE, SILVANA C.

THIENGO and ELLEN E. STRONG: "The results of the anatomical investigation confirm previous findings regarding anatomical organization of ampullariids generally, and Pomacea specifically.

Ampullariids are large to very large basal caenogastropods, and the only gastropods with both a monopectinate gill and a lung. Nuchal lobes are elaborated on both sides of the neck; the lobe on

the left elongated to a greater (e.g. Pomacea spp.) or lesser (e.g. Felipponea spp. and Lanistes spp.) extent to form a snorkel (referred to as a ‘siphon’ by many authors) that can be used to direct

air to the lung opening when the animal is submerged." p.745

From: "Physiology of the Apple Snail Pomacea maculata: Aestivation and Overland Dispersal" by KRISTY MUECK, LEWIS E. DEATON, ANDREA LEE, AND TREY GUILBEAUX

Biological Bulletin 235(Aug 2018):43-51":

1)In one experiment 80 snails were started to aestivate by putting them in air at 20C at 60% humidity. P44.

2)Experiment was stopped after half the snails died. That was 308 days. Half the snails survived 10 months out of water!!! P.46

3)Snails traveled 2 to 358 cm in 30minutes call it 180cm in .5 hours or 5'10" in 30minutes or 10' per hour (or about the width of the Live Oak Trail)--OVER LAND. P.47

4)Based on the present study, P. maculata can sustain travel over dry land for more than 3.5 h at an average of 2 meters per hr, sometimes covering up to 3.5 meters in less than an hour. p.49

5)This study has shown that the Louisiana invasive apple snail P. maculata is well adapted for survival in the absence of water. It can remain fully active under conditions of high RH, or it can

aestivate for long periods if the humidity is low. The ability of P. maculata to sustain travel over damp substrates and endure aerial exposure suggests that the reduction of water levels is less

likely to be as effective as has been reported for P. canaliculata. also p.49

Adult Apple Snails are very strong, and make a lot of toxic eggs. It seems like a grim situation, but there are allies already here in our environment that may be able to keep the snails from

overrunning everything. I've gathered images and video that I believe illustrate some of the descriptions I've read, and they're below. I have also put together an 8-minute long video that shows

some of the activities I describe here. Here's the video link. If anyone is curious about adult snails I've filmed--all of the adult snails that I filme were removed from wherever they were found and

were rendered unable to metabolize.

I had revisited Scobee Field on 7/17/2021--between the two visits described above. Although I shot the images shown below then (and some video) I decided to read more to try

to put some perspective on to what I had recorded. These are examples of the snails moving on land. Other snail species can do this, but this species-Pomacea maculata-is the destructive

invasive of concern. I found two separate examples showing how snails could push through thick vegetation and even leave a trail! The first two images below show one of these trails,

and also how long it was. The rake is 15 inches wide. Next is the snail, with scale to show size. The last image shows the shallow "ditch" and the remaining water in it.

Snail track in the grass. Rake =15 inches wide There's the snail. Snail is about 2.5 in (6cm) Water in shallow ditch.

The pictures below show other views of the same ditch. A snail was able to deposit eggs on a single twig (that must have been interesting). Then in that shallow puddle, I found 5 adult snails.

Two of them are shown in the 3rd picture below, with a closeup of one snail in the fourth picture. These pictures can be compared with others taken before and after this time (in sections above).

More of the ditch. Lone egg mass on a twig. Two snails in the shallow puddle. Snail moving in shallow water.

The first picture below shows egg masses on a tree surrounded by mud--many feet from the water. The last three pictures show a different track and the snail that made it.

There is water visible through the plants, but the snail is not submerged.

Egg masses on a tree, no water nearby. Snail track through the plants. The snail making the track. Snail moving over very shallow water.

At Scobee Field on 7/24/2021--The ditches dried, though the dirt was still damp. I noticed a snail shell in a hole in the mud. Since I'd read about these snails can aestivate, I took pictures of the

shell before I moved anything. I had already seen many snail shells lying out of the water in other locations, and they'd all been empty(dead). But just in case, I took many pictures of this one.

The depression, or hole, or whatever, was intriguing.

Snail in the dried ditch Shells of dead small snails litter the area Snail in the hole shot with flash Snail in the hole shot without flash

Then I turned the shell over. The snail was alive! I could tell by the sealed operculum. I took pictures of the snail and the depression. The hole wasn't elaborate, but it seems like the snail made

it. As of this date (9/29/2021) I haven't found any description of how Pomacea aestivate naturally. Do they dig burrows, or dig anything? I've read of one experiment shows that it's possible for

these snails to survive TEN MONTHS without water, as long as they can maintain a seal to conserve internal moisture. The snail had "backed into" the hole, so perhaps it could dig by

manipulation of its foot.

Snail flipped over. It's alive! Flipped snail next to the hole Closer view of the hole Snail near the hole, view shifted a bit.

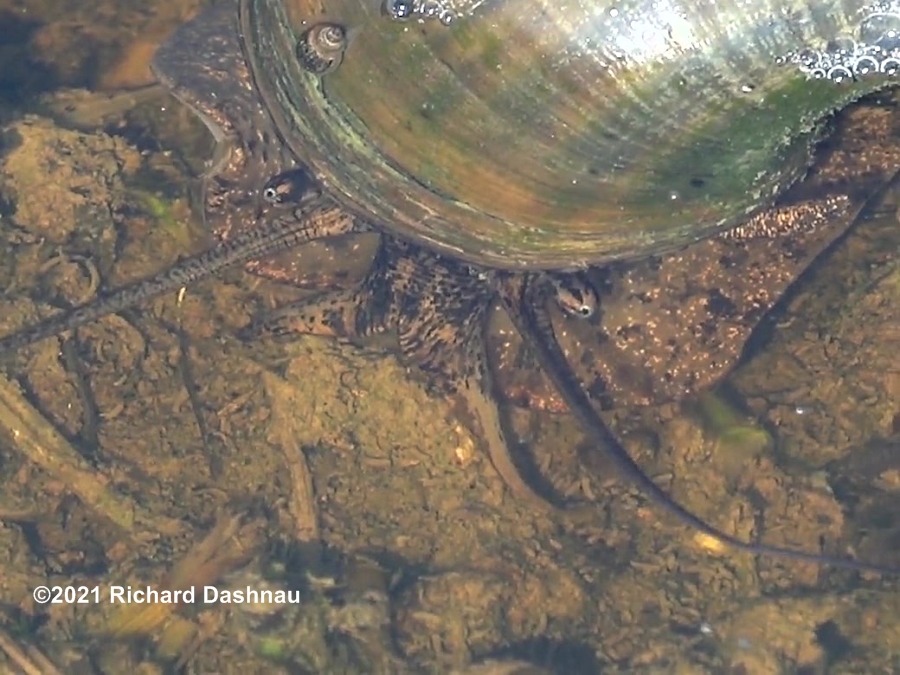

At Scobee Field on 8/17/2021--The ditches had some water again. I found an adult snail moving around in the water at one of the culverts. In this case, there were strings of amphibian

eggs in the water, too. I think they belonged to a species of toad. I've read that Pomacea will consume amphibian eggs as well as the various types of plants. So, I watched (and filmed) the

snail as it moved around the ditch and over the eggs many times. I didn't see any sign that this adult snail paid any attention to the eggs at all. The snail didn't pause, the eggs remained intact.

The video clips I captured are included in the edited video. Here's the video link.

Snail in the ditch with amphibian eggs. 1 Snail in the ditch with amphibian eggs. 2 Snail in the ditch with amphibian eggs. 3

At Scobee Field on 9/18/2021--A small bit of water appeared in the ditches. The pictures below show that the water hadn't been there long. But when I looked into that shallow puddle,

I found 5 adult snails. Where did they come from? How did they get there? I started filming, and this time I captured more interesting behavior.

Very shallow puddle in the same ditch. Live snails moving in the water! The water hasn't been there long. Two snails moving around mower tracks.

Apple Snails (and some other species of snails) have gills and a lung. This explains why the snails can go over land, or climb trees--etc. While I watched the snails moving around the

shallow puddle I noticed them probing with their "siphon". But the probe went straight up until it broke the surface of the water, where it opened. The siphon had become a snorkel!

Pinched-closed siphon reached up. Pinched-closed siphon breached the surface. Siphon begins to open. Siphon opening expands.

Siphon is now a snorkel. Siphon is now a snorkel. Breathing through the snorkel. Close the opening and submerge.

I noticed something else while the snorkel was being used. With the snorkel deployed, the head of the snail moved in and out; as if acting like a pump. The series of images below are frame

grabs from the video. They show how the head moved in and out. This is also shown in the same edited video clip. Here's the video link.

Snail's eyes, antennae, and face. "Air Pump" cycle, snorkel up, head is out. "Air Pump" cycle, snorkel up, head is in. "Air Pump" cycle, snorkel up, head is out.

Although these snails are pretty tough, there are already natural allies here that may help control them--that is, help stop them from taking over the environment. After all, they do have a natural

habitat (continent of South America), and are part of the ecosystem there. So, here are some of the animals on the Home Team:

1) Raccoons have been observed eating the adult snails--and they discard the toxic albumin glands. Here's a link to the article "Observations of Raccoon (Procyon lotor) Predation on the

Invasive Maculata Apple Snail (Pomacea maculata) in Southern Louisiana". And, here's a link to connected video showing raccoons with snails. The links were good when I used them.

Can't guarantee they still are.

2) Remains of Apple Snails have been found in stomach contents of alligators harvested in Louisiana. In article "ALLIGATOR MISSISSIPPIENSIS (American Alligator). NOVEL NON-NATIVE PREY".

Link to the article (in Herpetological Review, pages 627-628).

3) At least one native species of ant will attack snail egg masses. Surprise!! Not fire ants (although they might consider it). Article: "Observations of Acrobat Ants (Crematogaster sp.) Preying

on the Eggs of the Invasive Giant Applesnail (Pomacea maculata)" Link to the article is here. Link to a related video is here.

4) A native sunfish--Redear Sunfish (Lepomis microlophus) AKA "shellcracker" is known to eat small snails of many kinds, including young Pomacea. TPWD link here.

5) Limpkins! These birds are not native here, but have moved in to Texas, at least for the summer, and they are specialists in eating Apple Snails. As far as I know, Limpkins have not been

seen nesting here yet, so they might not have established a population here--so far.

6) Crawfish. Some crawfish are voracious. Native Red Swamp Crawfish (Procambarus clarkii) are for sure, and I've read that they will also eat young Pomacea. Which is good, since I've also

read that adult Pomacea snails can ravage crawfish habitat and also eat their young. So that's a few of the animals that can help control the growth of Apple Snail populations. Along with these...

are people. Scientists around the world have been trying create some kind of control but have not yet found one. In the meantime, collecting and destroying adult snails, and scraping snail eggs off

and into the water can help. I have done a bit of this at Scobee (removed about...70 snails total and maybe a hundred or so egg masses I think). And also at Brazos Bend State Park (only found

about 20 snails, but have removed about 400 egg masses off the trees along Live Oak Trail there.) This is not much compared to the efforts of some other groups of people at some other ponds

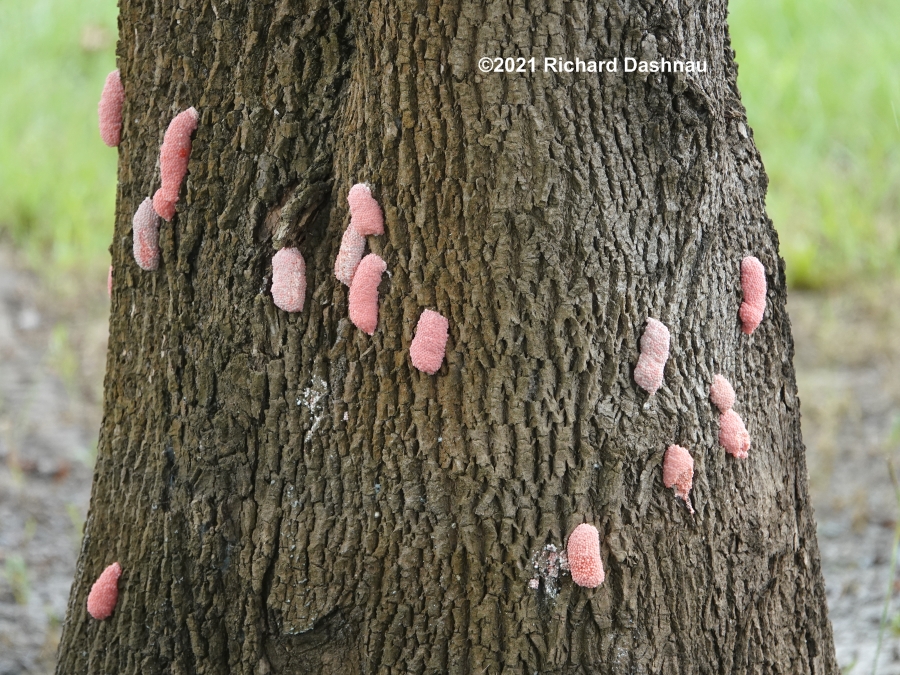

and lakes. The images below are from Brazos Bend State Park on 09/05/2021.

They will give some idea of the number of masses possible on the trail. I've found 180 masses along a 100-yard stretch in two hours. A short video demonstration of scraping technique is

in the same edited video.

7 egg masses, with old smears others. 4 egg masses, with old smears others. 4 egg masses, maybe different species 9 egg masses, with old smears from others

5 egg masses, from the picture of 9 13 egg masses, with old smears from others 12 egg masses, with old smears from others Scraping with paint roller handle step 1

Scraping with paint roller handle step 2 Scraping with paint roller handle step 3 Scraping with paint roller handle step 4 Rinsing toxic egg goo off of scraper.

04/24/2022. Springtime has brought new life and activity to the park. Over the last few weeks, people have starting seeing bright pink decorations on

some of the trees at BBSP. NO--I don't mean the Spoonbills (although they're here, too). I mean the egg masses of Apple Snails have appeared along the Live Oak Trail--mostly.

Unfortunately, the eggs are also appearing at other places now. I took a quick trip around the 40-Acre Lake trail to check on(the alligator mom--she and her pod seem to have moved away

from the den site where they wintered. I heard a couple alligator bellowing choruses, and some were close enough, or out of cover enough, for me to see them bellow. I went back to my car,

retrieved my "snail-egg removal tool" and went to Live Oak trail to look for Limpkins and pink eggs. At first Limpkins were around, but not very busy on our side of the fence.

Snail eggs were there, but most of them were on plants far away from the trail. I went to the second footbridge (going West to East), then turned around to scrape eggs on the way back. It

looked like area nearest the trail was too dry (or too shallow) for the snails to get close too the trees at shoreline. But, tree trunks that were accessible to snails were very "popular."

Snaileggs Image 04 (above) and 05(below) show a single trunk that had about 20 egg masses (some hidden by the tree) before and after the egg mashing. It wasn't the only one.

Snaileggs 06 (below) show an in-between Little Blue Heron being with some egg masses. When I was at the water's edge, I realized that there were hundreds of snail shells littering the mud!

Most of these were not full-sized shells, but mostly maybe 1.5 - 2.0 inch diameter shells, with some larger and some smaller mixed in. From what I've read of these snails, no weather-or other

natural event-happened at BBSP over the winter that would have killed that many--so were these all remnants of predator activity? WOW! While working back East-to-West I removed

113 egg masses. But there were many, many more eggs on plants out in the water where I couldn't reach them.

I think Egg masses stopped appearing near the trail a little West of the first footbridge (but I'm not sure exactly where). A single Limpkin foraged even further West, in an area that looked

drier to me. But, I'm not the snail-hunting expert. Some time later, I returned to 40 Acre Lake.

Update 05/19/2022 - From BBSP on 05/15/2022 Springtime at BBSP has been quite pink lately. Some of the pink is good news but, unfortunately, some of the pink is bad news. Bad pink

first: The apple snails are still at work on the Live Oak Trail. I walked down to the second footbridge, then turned around to scrap eggs off the nearer plants. As the first photo shows,

the snails use whatever they can use to lay their eggs out of the water. The water level in the swamp is low, and most of the plants near the trail have been knocked down. This limits

the climbing points available to the snails. But, as the pictures show, the remaining exposed climbing points are VERY popular--and they are covered by egg masses.

I removed about 140 egg masses (and my scraper broke); but they were concentrated along a relatively short stretch of the trail. The last three pictures below show the same tree with eggs

from two angles (the arrow points to a "3-lobed" clump that changes perspective). I count about 40 egg masses on that single tree! The last image shows the tree after scraping.

The Limpkins are still over there, I took a few pictures of them--just because I can. Limpkins...in Texas.

That was the "unwelcome" pink. The "good" pink was Spoonbills, on another page.

05/27/2023 I went to Scobee Field to see what the rain a few weeks before might have affected. The area was mostly dry, although there was a little bit of water in the

ditches near the road. I examined the dried ditches to see what sort of burrows were left, and I found another example of an Apple Snail in a burrow! Although they live in

water, Apple Snails can aestivate in mud during dry periods for 10 months! There were a few egg masses on the culvert near the restrooms even though the ditch was

dry. So I knew that adult snails had been around. Then I saw this hole that contained 2 snail shells.

I used a metal rod I'd found in the area to measure the depth to the top of the snail shell--about 5 centimeters. When worked the snail out of the hole (it was a tight fit), I

found that the snail was alive. The operculum was sealed across the shell opening and was being held tightly closed. I was taking pictures with my phone, and in the

bright sunlight it was hard to focus into the hole. But I got a few, that show the bottom was rounded across the width, and pretty smooth. How does an Apple Snail dig,

anyway? Of course, the hole was dug while the bottom was still soft, as the water was evaporating. The snail was about 5cm...long?

The hole was about 5-1/2 cm across (of course, "snail-sized"). I used the same rod to measure the depth of the hole--about 9cm! I still can't find any images of Apple Snail

burrows anywhere online (although I can find mention that they do burrow to aestivate). This is my second direct observation of an Apple Snail in a burrow. The first one

was also at Scobee Field, and is shown on this page , as well as one of my ichnology (animal traces) pages here.