Welcome to the Visitor's Center at Brazos Bend State Park. That's me on a trail (03/29/2004). As I got more pictures, these pages expanded. I've gotten enough images of snakes

to collect them on my snake pages.

Snakes page 2 nonvenomous 2003 -2004 Snakes page 1 nonvenomous 2003 -2004

Snakes page 3 nonvenomous 2003 -2004 Snakes page 6 Rat Snakes 2002 - 2021

Snakes page 4 nonvenomous 2006 -2021

Snakes page 5 nonvenomous 2022 -2023

----------------------------------

Welcome

to the Visitor's Center at Brazos Bend State Park. That's me on a trail

(03/29/2004). As I got more pictures, these pages expanded. I've gotten enough

images of snakes

to collect them on my snake pages.

--

--12/21/2014 It's Near Christmas, and it was in branches...

I was driving back towards the Visitor's Center, when Chuck flagged me

down as he drove his truck in the other direction. He told

me of a

juvenile Copperhead that was hiding (in plain sight) up in some

branches, and he told me where it was. Some hours later, I went looking

for the snake on my way out of the park. And

I found it. The first

image below left is a composite of 3 shots showing the where the snake

was relative to the trail. The remaining images are views at various

zoom distances. I was very

impressed that the "leafy" camouflage

pattern seemed to work well among the branches 5 feet off the ground.

The

closest view shows the extra pit (near and just below the eye) and the

elliptical pupil that helps identify a pit-viper. I was stayed

relatively far from the snake, and it remained immobile

during my

photo-shoot. In the book How Snakes Work, by Harvey Lillywhite,

there is some discussion about the function for the colors of snakes.

(p129) Snakes that are marked with patterns

of blotches, spots, etc.

usually rely on concealment (called "crypsis" in the book) to hide from

potential predators. This copperhead is an excellent example of this. The

book goes on to say

that many (but not all) species that use "crypsis"

will aggressively defend themselves when their stategy doesn't

work-instead of trying to crawl away. This might be related to them

being unable

to crawl rapidly. Howver, the book goes on to say that

there are many exceptions to this. In the second picture, the

lighter (green or yellow) tail of the juvenile Copperhead can be seen.

As the

Copperhead gets older, the tail loses this lighter color. The

young Agkistrodons-Copperheads (A. contrortrix)and Cottonmouths (a.

piscivorous)-both have these lighter-colored tails. And, the

tails are

used in a behavior called "caudal luring". The tail can be used as

"bait" for prey for the snake--or as "bait" against a predator to

distract it from the snake's head. I have shot video

showing a juvenile

Cottonmouth using its tail as a distraction. Contrast this with

snakes that have stripes or similar uniform patterns. These tend to

rely on active escape by moving quickly away

from predators (p130).

This general behavior has been observed in a species of garter snake

that can have coloration that varies from striped to blotched. Striped

snakes tended to crawl away

when disturbed, while the blotched were

more likely to move a short distance and then stop completely. This

behavior is called a "reversal" and is used along with crypsis after

the snake has

been discovered. The movement and rapid stop can

confuse the predator; since it has been tracking movement, it appears

the prey has suddenly disappeared when the prey stops and blends

back

in. I assume that this is further aided by the tendency of the vision

to continue tracking along the percieved path of escape. I

have heard that this is how rabbits and deer can use the white

"flag"

of their tails as they escape a predator. They run, showing the tail,

then suddenly stop and hide their tail. Their natural color blends in

with the environment. Meanwhile, the predator has

been tracking a

white, high-contrast object through the woods which has suddenly

disappeared. The predator then has to bring their focus back along the

percieved track of their prey--which

has stopped moving, and will be

hard to see again. The striped (lines going head-to-tail) snakes

also have another weapon-optical illusion. (p130). Recognizing a moving

object and judging

its speed depends on the relationship of the color

pattern on that object and surface where it's moving. Striped snakes

can appear to be immobile even when they are moving--or can seem to

be

moving slower than they actually are. Since there is a continuous line,

it's hard to pick out a recognizable point, especially when the snake

is moving. I finally realized this after years of

watching snakes when

I watched it in action in a field. I recognized a ribbon snake in the

grass. I stopped moving, and looked down at a gap in the grass. I tried

to see the head, but wasn't sure

which way the snake was pointing.

While I was looking down at the snake I had thought was lying still;

the tail suddenly appeared in the gap--and the snake was gone. The

snake had been

moving all along! I have examples of 2 ribbon snake

moving. Exposed in high-contrast by being out in the open on a trail,

the movement can still mesmerize. The 2 images below are a screen

grab

from each clip. The links to the clips are here 051914wmv 051914mp4 and here 072014wmv 072014mp4.

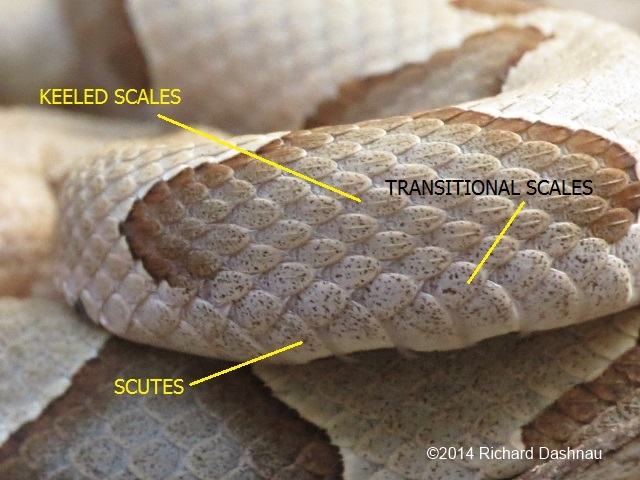

One

more thing is visible in the close views of the Copperhead. All of its

scales are not the same. Copperheads have "keeled" scales. These are

scales that have an additional ridge in their

center, that runs

lengthwise with the snake. Not all

snakes have keeled scales. Then, there are the broad scales that most

snakes have on their underside-which are called "scutes" (P.120)

Then, between the two types of scales, there is a line of

"transitional" scales, which don't have keels, but are not full scutes,

either. Since I gave no sign that the Copperhead's crypsis was

unsuccessful, it remained still; and I finally went home.

09/03/2006--I

had just started around the 40 Acre Lake Trail when I encountered a small

Southern Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix contortrix). I'd heard

it move through the leaves,

and when it stopped, I started taking pictures

of it. The first image below shows the snake looking up at me. (Also see

ONE and TWO, below. They are both are from the same image).

In image TWO,

the two heat-sensitive pits (which define the pit-vipers) are clearly visible.

The elliptical pupils are also visible. As I bent towards the snake (but

not very close at all), it

struck at me!

Since

the snake was acting so nervous, I decided to try to herd it off the trail.

Knowing that it would strike at least once more, I shot a short video clip

with my still camera

as I moved the stick closer to it. Images THREE and

FOUR below are single frames from this clip. The camera shoots video at

24 frames per second, non-interleaved. Even at that

speed, the snake's

strike is blurred. The links to the video clip is below. First is the clip

at actual speed. The other two clips are parts of the same clip digitally

slowed down to .2 normal

speed. (I'm assuming this is less than half normal

speed).

DEFENSIVE

STRIKES ACTUAL SPEED 2.5MB DEFENSIVE

STRIKES .2 SPEED A 1.8MB DEFENSIVE

STRIKES .2 SPEED B 3.1MB

To my

surprise, the Copperhead would not back down from me, but continued facing

me. This illustrates an important point. Most animals are content to be

left alone. Any animals enountered

on the various trails (like snakes or

alligators but also including deer or raccoons or other "cute" animals)

are generally on their way somewhere when they are discovered. If left

alone, they

will generally continue on their way. Sometimes a reptile will

pause to rest. If it is not ready to move, or, if it feels threatened;

then the animal may go into a defensive mode. In this case, it will

face

the enemy (which could be *you*, if you are bothering the creature); and

turn its defensive weapons towards the threat (you). Worst cases can be

fangs, teeth, or claws. Aside from the

"hard" weapons mentioned above,

there can also be various musks, urine, fecal matter, vomit, or various

other chemical weapons--this, of course, depends on the animal. The point

here is

that it's just best to leave the animals alone. In any case, these

weapons are intended to deter an attack.

The

only reason *I* was moving the snake was because it was obviously already

stressed, and I wanted it further away from the trail (and potential interaction

with park visitors. I finally persuaded it to move on, and I took

a few more photos. Images SIX, SEVEN, and EIGHT,

below, are three cropped

versions of the same image. While the snake has relaxed its body, you can

see it's still watching me. Remember--I

WORK FOR THE PARK. Do NOT molest, or catch,

or kill ANY snakes at the park.

--

-- --

-- ----

----

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

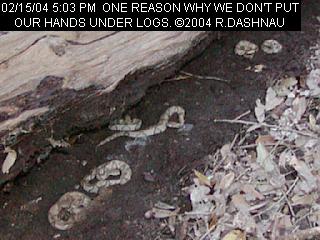

The

picture below (SIX COPPERHEADS) is a picture of the other interesting item,

and to further clarify what the caption says, it's a good illustration

of "Why We Don't Put Our Fingers and Hands

into Places We Can't See."

This item, relayed to me by David-and discovered by Rich and Sandy Jesperson

and Carol Ramseyer I believe- was a group of six young copperhead snakes

under

a log.

-

- -

-

SIX COPPERHEADS

TWO ON THE LEFT

CENTER TWO

- -

- -

-

WE'RE JUST BUDDIES!

REALLY!

TWO ON UPPER RIGHT

After

looking at the alligator with its nutria, I went and looked for the log,

which turned out to be less than 5 minutes' walk from one of our parking

areas. CAREFULLY lifting the log (so I wouldn't

disturb, or crush

the snakes), I was very happy to see what I show in the pictures above.

They follow in sequence in the RICKUBISCAM image from lower left to upper

right, diagonally. Note the

extra little friend, a toad, lying next

to the center, extended snake (WE'RE JUST BUDDIES, above). The toad, like

the snakes, was seeking shelter from the cool weather, and is obviously

alive.

I estimate the snakes to have been between 8 and 10 inches long.

Since they are all curled-and I did this quickly to avoid disturbing the

snakes enough to make them move; and also before any

park visitors might

come along-there was no way I could measure them. My usual use of a quarter,

or any other method of measurement that would require me to put my hand

near the snakes

was not an option.

Now,

remember this lesson. You can never be certain of what is under any large

object you might find in the woods. It could be one snake,

which may or may not be

venomous, or it could be SIX snakes, which may

or may not be venomous. In this case-copperheads-they were all venemous,

and if someone reached under this log to lift it, they could have been

bitten at least six times (more, if any of the snakes struck more than

once). If you must move something, then use something that won't be injured

if it is bitten or stung. Remember that in a State

Park, it is against

the law to disturb or harass the wildlife (this includes snakes). This

is also why it is best to stay on the trails at all times. So, if you are

using a State Park as you should, then this

situation shouldn't even occur.

-----------------

------- -------------------

-------------------

ONLY DANGEROUS IF YOU BOTHER IT

------------------------------------------------------------

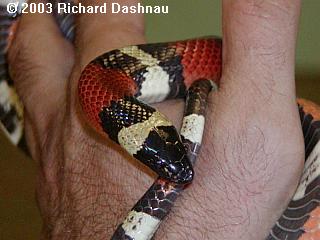

BEAUTIFUL!

After

today, it will be released in a secluded section of the park, to live free

once again. Coral Snakes like to eat small lizards, amphibians, and other

snakes. Unlike the snakes that we do keep

in the VC/NC, Coral Snakes

don't do well in captivity. In the picture below (RED TOUCH YELLOW) you

will see the color scheme that will warn you that this is the venomous

Coral Snake. The

bands of yellow touch directly on the bands of red. The

black "patches" in the red bands help distinguish it from the Eastern Coral

Snake. Note also in the picture of its head (CORAL SNAKE

HEAD, below)

that the head is very small, and the eyes aren't very prominant. Do not

be misled by the apparent size of this creature. Regardless of the size

of its head, like *any* snake, the Coral

Snake can open its mouth wide,

and the poison it produces is a potent neurotoxin (Coral Snakes are in

the same family as Cobras and Mambas). Compare the color scheme with

that of a

Mexican Milk Snake (Lampropeltis triangulum annulata) (see RED

TOUCH BLACK, below); one of many non-venomous snakes species that mimic

the Coral Snake's color scheme. This

particular snake is not native to

our vicinity, though. Notice that the bands of red touch directly on the

bands of black (unlike the Coral Snake, where red touches yellow). This

is true for all of the

various species of non-venomous King and Milk snakes

that have this similar color pattern. A look at the Milk Snake's

head (see MILK SNAKE HEAD, below) will show that the head is a bit larger

in relation to the body, and the eyes are much more prominent, than with

the Coral Snake. Also notice that I am holding the Milk Snake (yes,

that's

my left hand), and definitely *not* the Coral Snake.

Both

snakes are beautiful, aren't they? Yes, they are. Both eat small reptiles,

including snakes, as well as other small animals; although the Milk Snake

will also take rodents, while evidently the

Coral Snake does not.

Finally,

here

(flv video 552 kb) is a short video clip of the Milk Snake exploring

my hand. This snake has been with the park at least for the two years I've

been there, and is

obviously used to being handled. The image below (MILK

SNAKE VIDEO) is a single frame from the beginning of the clip. Incidentally,

the Mexican Milk Snake is not found in our park (its range

is more

Central Texas), but is kept there to show an example of this mimicry. Animals

will sometimes try to emulate the shape and/or color of a similar species

that is more dangerous; so that

predators may leave them alone.

-

- -

-

RED

TOUCH YELLOW

CORAL SNAKE HEAD

RED TOUCH BLACK

- -

-

MILK SNAKE HEAD

MILK SNAKE VIDEO

----- - ---------

--------- -------------

-------------

3 FANGS BEFORE

WHERE'S THE INSTRUCTION MANUAL?

September

22, 2002Suppose

for a moment that you have just pulled into Brazos Bend State Park, and

as you enter the park, your brain registers the image of an upside-down

snake on the side

of the road. You drive past, as your mind catalogs the

event. What do you do next?

Well....I

drove a second or two more, and then thought: "Interpretive Material!",

and I stopped the car (after, of course,

being sure there was no one behind

me.) I then backed up, and passed the snake again. After retrieving

one of my Tallow-Whacking machetes from the rear of my car, I moved towards

the snake.

After carefully prodding it over, I saw that it was a

Water Moccasin, or Cottonmouth (agkistrodon piscivorus), and that it was

dead. This was easily determined by noticing that it had already been found

by fire ants, and NOTHING will sit still while being attacked by fire ants.

This snake is one of 3 pit-vipers that used to be found in the park (the

Canebrake Rattlesnake is thought to be extinct in the park),

and is

venomous. The head was intact, so I cut it off and slipped

it into a small plastic container (film case) that I had in my car for

just such an occassion. Then I put the case into my vest pocket (well

THAT'S

what the pockets are FOR!).

Later

examination of the head while photographing it revealed a few things. The

image below shows a side view of the head as I hold it between my fingers.

(NOTE

THAT I USED EXTREME CARE WHILE HANDLING THIS SPECIMEN, EVEN THOUGH IT WAS

DEAD! ALSO NOTE THAT THIS SNAKE WAS ALREADY DEAD! I'D NEVER

CONSIDER KILLING

*ANY* SNAKE IN THE PARK.)

---------------

Pictures

below show: The extended fangs (MOUTHOPEN1); Closeup of both fangs (MOUTHOPEN2);

the right fang (RIGHTFANG1). As I was pushing on the fangs for these

pictures, I noticed fluid

appearing on the fang. I assume that this was

venom I was forcing from the poison sac (RIGHTFANG2). THIS

IS WHY CARE IS NECESSARY WHEN HANDLING DEAD VENOMOUS SNAKES.

The

teeth are like needles, and a slip on my part could cause an injection.

Some

sharper-eyed people may have noticed something odd in the first two pictures.

The left fang is is a double fang! This

picture (LEFTFANG1) shows a closeup

of that structure. David, the park naturalist, says that from time to time,

the snake will grow a replacement fang. As this grows, it moves alongside

the previous

one, until the older one finally drops off. If I'd thought

about it, I could have tried to force venom out, to see which fang it would

flow from. But...I didn't think about it, so it's unknown to me.

Oh, well, I can't

think of *everything*. In any case, visitors to

this page can now say that they've actually seen pictures of a three-fanged

Water Moccasin!

-

- -

-

MOUTHOPEN1

MOUTHOPEN2

RIGHTFANG1

After

all this, I began a treatment of the head which I hope will allow me to

strip the flesh off and maintain enough structure for me to rebuild the

skull--WITH the double fang. That will be an interesting

display!

Please

note that like all animals in the park, the snakes, including the venomous

ones, are part of the ecology. They perform a function like *all* predators.

They are harmless to humans when

left alone (to their PREY, on the other

hand, they are BIG TROUBLE). Care should be taken while walking in

*any* wild area for a number of reasons. The great majority of the

snakes in the park are

non-venomous. The presence of these-and any other-reptiles

in the park should be no cause for alarm. Brazos Bend State Park

is an amazing and unique natural resource and an area with a

varied number of animal and plant species. On a single good day at

the park, it is possible to see as many wild creatures as most people

would see in a year...or even in a lifetime.

On the other hand, if

the interpreters (like me) at the park do what they hope to do, then

visitors who leave the park will see more wildlife everywhere.

Because they'll start to notice it!

May

05, 2002 Tuesday,

April 23, I got to the park around 8:00 am. I hadn't been on the trail

10 minutes (I started at the 40-Acre Lake parking lot), when I encountered

a

copperhead stretched across the trail near Hoot's Hollow. I

was able to take a few pictures before it got bored with me and continued

across the trail.(COPPERHEAD,

above) Notice the coloration

of the scales and the shape of the head. Also, the nostril is the small

opening at the tip of its nose. You might notice another opening between

the nostril and the eye. This pit is what gives "pit vipers" their name.

It's a heat sensor, and aids the snake in stalking food. Copperheads are

poisonous, and as stated in

signs throughout Brazos Bend State Park, "POISONOUS

SNAKES EXIST IN THIS PARK". The snakes belong in the park. Humans

are only visitors there. Visitors should

keep a close eye on their children

and pets while they are in the park, for this reason.

Snakes page 2 nonvenomous 2003 -2004 Snakes page 1 nonvenomous 2003 -2004

Snakes page 3 nonvenomous 2003 -2004 Snakes page 6 Rat Snakes 2002 - 2021

Snakes page 4 nonvenomous 2006 -2021

Snakes page 5 nonvenomous 2022 -2023

Go back to my home page, Welcome

to rickubis.com

Go

back to the RICKUBISCAM page.