Apple Snails (Pomacea sp.)

This

page was born 09/28/2021. Rickubis designed it. (such as it

is.) Last update: 9/29/2021

Images

and contents on this page copyright � 2021 Richard M.

Dashnau

Here are my other Brazos Bend

and/or critter pages:

----------------------------------------------------------------

OR, FOR OTHER ANIMALS:

Alligators

at Brazos Bend State Park Introduction

Critters at Brazos

Bend State Park Page 1

Snakes-nonvenomous

1-------------------------------------------

Critters

at Brazos Bend State Park Page 3

Snakes-nonvenomous

2-------------------------------------------------Insects,

non-toxic

Snakes-nonvenomous

3------------------------------------------------Spiders

Snakes-venomous------------------------------------------------------Mammals

Birds-Waders----Birds-Raptors---------------------------------

Lizards!--Turtles!

Cookiecutter

Shark Attack! Hammer-headed

Worms Acid-Spitting

Arthropod

-Today

is 9/28/2021. I hadn't known anything about Apple Snails before July of

this year. Since then, I've read a lot about them, found them,

filmed them, and tried to help control them.

I quickly gathered a lot of imagery and information about them, so...here it is.

07/08/2021 - 07/10/2021 A

friend of mine told me about seeing Apple Snail egg clusters along the

Live Oak Trail at BBSP. He also mentioned that Limpkins had

appeared in the area--since they are

known to eat adult apple

snails. I'd only recently learned that the egg masses of Apple

Snails look like wads of pink bubble gum stuck on surfaces near water,

because I'd seen one mass on a tree in

Houston, at Fiorenza

park. Just *one* mass, and at the time I didn't know what it was.

I haven't seen any there since. But, about a week ago, I noticed

a few egg masses at Scobee field, but hadn't

thought much about how

they got there and what they meant. But then I started reading

about them. And I went back to Scobee for another look, and took the

pictures here. At some time recently,

most of that park must have

been flooded. This makes sense because that entire area is *inside* the

Barker Reservoir-a flood-control structure which is designed to capture

water. Anyway, I went

there between bouts of rain, so didn't

have a lot of time this trip. The pictures are all of the same

area. Note where the eggs are. The masses on the "bridges" over

the ditch aren't a big surprise

(there's water in the ditch) but

then there are masses on the tree, and on the picnic table. Water must

have been higher. I didn't see any snails this trip. Also, I dealt with all the egg clusters I took

pictures of (and more that I didn't get pictures of).

Egg Aftermath

Then

I did more research. The source I liked best--which seemed

relevant to Texas was this one: Identity, reproductive potential,

distribution, ecology and management of invasive Pomacea maculata in

the southern United States

(by Romi L. Burks et.al. 2017). This book was also very informative:

Biology

and Management of Invasive Apple Snails ed. Ravindra C. Joshi,

Robert H. Cowie, Leocadio S. Sebastian 2017. It also

contains the prevous study. I found the book in many places online.

Here's one link: https://enaca.org/?id=931

This

is what I've learned. The term "Apple Snail" is too

general. Over time, it has led to some confusion while discussing

these animals. In the Southern U.S., the species Pomacea maculata

is the most widespread.

P. maculata were probably introduced

here through mishandling of the snail by aquarium owners. The snails

can keep enough air in their shell to allow them to float. Then,

if the body of water they are living in

became flooded (like in a

hurricane. Harvey, for instance.) the water can carry them everywhere

and anywhere. Perhaps that's how they got to Scobee field.

P.

maculata lay eggs on surfaces above the water line, usually

during dawn and dusk. A normal clutch of eggs is about 1500-2100

and takes about 30 minutes to deposit. The eggs hatch in about 2

weeks, and can yield

hundreds of hatchlings. The best hatching

results if the eggs remain dry for 6 - 9 days. Any submergence during

this time can affect the stability of the eggs. The eggs are also

toxic, possibly a by-product of the same

chemistry that allows

them to incubate in open air. Their bright pink color may also serve as

a warning against being eaten. P. maculata apparently eats almost

everything. Like many snails, P. maculata eats periphyton

(algae,

detritus, etc. that cling to surfaces); but they also eat macrophytes

(larger plants that are visible all the time...duckweed, rice,

lotus). In Louisiana, they are of major concern for rice farmers,

as the snails will

eat young plants. The snails will also

eat crawfish eggs. Although the eggs are toxic, the newly-hatched

snails are fair game. It's possible the young snails could be eaten

while they're growing by the predators that are

usually

around--crustaceans, insects, fish, turtles, wading birds and some

mammals. Some crawfish species seem to prefer P. maculata hatchlings to

those of native snails. The birds called Limpkins don't normally

live in

Texas, but some have recently been observed here eating

Apple Snails!! One more thing--P. maculata-like many snails-are

inhabited by many parasites. Some of these are dangerous to

humans. One worm in particular--

Angiostrongylus cantonensis (aka

Rat Lungworm) is pretty nasty. It is generally spread to humans

when they eat improperly-cooked snails.

The book I mentioned above

gives a very good view of how many countries are trying to control the

damage being done by the various species of "Apple Snails". The

studies are good examples of what major incursions

of the snails

look like. They look BAD. A common method of early control is to

destroy egg masses whenever they are found, and capturing and disposing

of adult snails. In both cases, care should be taken to avoid being

contaminated

by contact. Also, I haven't found very much descripton in what do do

with snails after they're collected. It is illegal to transport the

snails in many places--to prevent further contamination. I suppose

crushing

them in place is an option (but not very humane...which

might be why it isn't suggested often). I've also seen references

to freezing them....for a few days to be sure they're dead. It appears

that P. maculata can also survive

short exposures to freezing

temperatures. Now, when I look at my pictures, it seems

that there isn't really much at that park there for adult snails

to eat. The hatchlings might be able to live off periphyton for a

while,

but there isn't much else. And, once the rain stops, those

ditches are normally dry over the summer. Between the wading

birds coming in to clean out the wet ditches, and lack of water,

perhaps the snails who have ended up

at Scobee will mostly die

anyway. To be sure, I did make sure to smush all the egg masses I

took pictures off--plus more that I didn't.

On 07/10/21,

I returned to Scobee Field. I went early, hoping that I could catch a

snail laying eggs. And, I did! I shot some pictures of the

snail at work, and some video clips as well. If you examine the

pictures below,

you'll see how much more water there is. It

rained a lot Saturday. The model airplane group that runs Scobee

Field were having an activity there, so I didn't stay in their way

(They were perfectly friendly. I just didn't want

to be in the way.) There was one snail at work, so I filmed that one. The video is here.

I was amazed when I saw how the eggs were carried out of the

snail, and up to the wall. There was a sort-sort of trench in the

snail's

flesh. But, it wasn't a defined structure. It changed shape,

and other dimples formed to carry separate clumps of eggs. Pictures in

the bottom row below show this....trench. The video shows it

working. The final picture

shows an empty shell that was there.

Something had eaten most of the snail out of it. There were lots of

wading birds around that morning. One of the folks walking around

suggested that raccoons might eat the snails.

That's encouraging,

but I have a question (at least one, anyway). Since the eggs are

toxic-which prevents most animals from eating them (the bright pink

color might act as a warning (aposematic coloration)); then what happens

to

animals that eat a snail that has eggs inside? Also, the egg

masses I saw, and the snails I found--were removed carefully.

They're gone. Since I always carry hand disninfectant, I used it after this.

Egg channels The shell is not smooth everywhere. Something ate most of this one.

07/25/2021 and 08/01/21- I've

been doing more research on our apple snail invaders since July. When I

saw the inside of an adult Pomacea, I noticed orange masses or organs.

I

figured that those were eggs. Since the deposited egg masses are toxic,

I wondered if the eggs inside the snail were also toxic. And, if the

eggs are toxic--how can any animals

--such as Limpkins--eat the

adult snails? After a lot of searching, I couldn't find any

detailed description of how this situation is dealt with. The

first picture below was

taken on 7/24/21, but I'd seen inside other

snails before then. The other two pictures were taken 7/10/21,

and show a snail that something had eaten. At the time, I hadn't

realized that the toxic egg masses had been left inside the shell.

I found a number of references saying that animals that eat the snails discard the albumen glands. But the only predator I saw named doing this was Snail Kites. But no clear descriptions.

I started searching for proof that Limpkins

might discard these organs. I found a video on youtube that shows a

Limpkin doing this! After that, I started looking around BBSP for

signs

of this behavior.

But let's pause a bit.

Limpkins? Limpkins (Aramus guarauna) are long-necked wading birds

with long, pointed beaks. They're about the size of Night Herons (maybe

a bit larger).

According to Avibase, the World Bird Database,

it is the only extant species in the genus Aramus and the family

Aramidae. The "home range" of 4 subspecies of Limpkins is: Florida,

Cuba,

Jamaica ; southern Mexico south to western Panama;

Hispaniola and Puerto Rico; central and eastern Panama; South America,

south west of the Andes to western Ecuador, and east of the Andes

south

to northern Argentina. Like many wading birds, Limpkins can be

generalist predators but according to many sources, the greatest

component of their diet is: Apple Snails. If we examine the

list of regions in their "home range", we can see something missing-- TEXAS. That's right. In fact, their home range is far from Texas.

Texas

is now being invaded by Apple Snails. If only Limpkins were in

Texas! Well...they ARE in Texas. In fact, they have been hanging

around in the lake next door to BBSP for some months now.

That

lake is infested with snails. Unfortunately, the snails have made their

way to the BBSP side of the fence, along Live Oak Trail. But the

Limpkins have been picking them off there, also.

Discarded

snail shells litter the trail. I went down Live Oak Trail on 7/18, and

I saw something interesting among some discarded shells. I took a few

pictures. Next to one

of the shells is a pink mass. I think that

mass is one of the "albumen glands" that was discarded by the Limpkin

that ate that snail. The trail was really wet, so I didn't go further.

First

3 images below show shells on the trail, and a pink mass neer them. The

last image was taken there on 8/1/21, and shows pink material in the

discarded shell.

I

returned to Live Oak Trail the next week (7/25). I'd been around

the other trails, and entered Live Oak from the East end and walked

West. I was doing snail egg removal. It was Noon,

and it was

hot, so I didn't expect to see anything. A Limpkin appeared on

the South side of the trail, near the fence, and hunted the area near

the fence. I stayed back, and hardly moved.

It came to

the trail, walked on it a bit, then went back under the fence and

eventually up the levee and across. I got pictures and a bit of

video! This is all edited into this video.

Next

weekend (8./01). I'd been out on the other trails first. I met a couple

park visitors I'd sent to Live Oak trail and they told me they'd hadn't

seen any Limpkins, but had seen snail egg masses,

and even a

few live snails. So I was on Live Oak Trail again, at about

12:30pm. I'd gotten almost to one of the "bridges" when I saw a

Limpkin up in a tree between the trail and the

road--that is,

North of the trail. I watched it for about 20 minutes, until thunder

from approaching rain clouds convinced me to start back to my

car. I got a brief look at another Limpkin

in a tree near

the one I'd been watching. They both moved, and seemed to start

hunting, but I didn't want to get caught in rain that seemed to be

approaching. I got photos and video

clips. Again, this has all been edited into this video.

And,

I found another snail shell that seemed to have remnants of a discarded

"albumen gland" in it. I also found another paper that seems to

have been inspired by the habit of snail predators

discarding the

"albumen gland": "Apple Snail Perivitellin Precursor Properties

Help Explain Predators’ Feeding Behavior" 2016 by Cadierno, Dreon,

Heras. While it discusses Pomacea canaliculata and

not our

problem (P. maculata), I think it's still related. This study is where

I got the term "albumen gland" for the organ which produces the snail

eggs. Perivitellin serves as a nutrition source for snail

embryos

(similar function to egg yolk ). While the paper is a bit technical for

me to fully understand, for me it verified: a) that the

organs are toxic, and therefore consumption of the entire snail

could be dangerous; b) that experienced predators do discard toxic parts of the snail, rendering it safe to eat. From the paper: " Therefore, as the noxious perivitellin precursors are exclusively

confined

within the AG, this explains why it is the only usually discarded

organ, even when this behavior implies a large loss of the total energy

and nutrients available from the soft-body biomass

(Estoy

et al. 2002). Finally, we propose that the reddish-pink gland color may

contribute to this behavior, helping the visual-hunting predators of

adult snails to associate the bright AG color with the

noxious compounds it carries."(page 466 "AG"=albumen gland)

This could be trouble for our local predators (such as alligators) that

might consume entire snails. Raccoons might be able to identify

and

remove the glands, but they'd have to learn about the danger first (that might be what ate the snail in the picture above).

It's potentially good news that Limpkins are eating snails here. It

will

be

better news if they establish a breeding population in

Texas. They can help control the spread of the Pomacea. But, regardless

of predation, and it seems to me that the snails will remain. I

think

the

most we can hope for is that the predators that have followed the

snails (and other local predators) and the snails will reach a

"balance" where the snails will not overpower the environment.

There

must be reasons why Limpkins haven't made the journey here before. If

lack of snails was a factor...where they're here now. But, if there are

other environmental reasons (such as temperature)

the Limpkins may not

stay. I hope they do.

My

Big Apple Snail Followup, written

09/28/2021-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Update 09/28/21- I

made repeat "snail expeditions" to Scobee afterwards. I scraped

off egg masses, and on one visit removed 52 snails--and those were

moving around in the drying ditches and trenches.

One might think

that we could just leave them alone and the snails would eventually dry

up and die. After all, they're only snails, right? But these are

*really tough* snails. LOL

They

have been observed feeding in water at 2deg C . In hot dry weather

they can aestivate and can survive easily in 15 - 35 C ( 59 - 95 F) (from: "Identity, reproductive potential, distribution, ecology and

management of invasive Pomacea maculata in the southern United States" by Burks et. al. Page 305)

Oh...and this species has a gill and a LUNG. An actual, vascularized lung--which allows them to breathe while out of the water.

From:

"Comparing apples with apples: clarifying the identities of two highly

invasive Neotropical Ampullariidae (Caenogastropoda))" by KENNETH

A. HAYES, ROBERT H. COWIE, SILVANA C. THIENGO

and

ELLEN E. STRONG: "The results of the anatomical investigation

confirm previous findings regarding anatomical organization of

ampullariids generally, and Pomacea specifically. Ampullariids are large to very large basal

caenogastropods,

and the only gastropods with both a monopectinate gill and a lung.

Nuchal lobes are elaborated on both sides of the neck; the lobe on the left elongated to a greater (e.g. Pomacea spp.) or lesser

(e.g.

Felipponea spp. and Lanistes spp.) extent to form a snorkel (referred

to as a ‘siphon’ by many authors) that can be used to direct air to the

lung opening when the animal is submerged." p.745

From:

"Physiology of the Apple Snail Pomacea maculata: Aestivation and

Overland Dispersal" by KRISTY MUECK, LEWIS E. DEATON, ANDREA LEE, AND

TREY GUILBEAUX Biological Bulletin 235(Aug 2018):43-51":

1)In one experiment 80 snails were started to aestivate by putting them in air at 20C at 60% humidity. P44.

2)Experiment was stopped after half the snails died. That was 308 days. Half the snails survived 10 months out of water!!! P.46

3)Snails

traveled 2 to 358 cm in 30minutes call it 180cm in .5 hours or

5'10" in 30minutes or 10' per hour (or about the width of the Live Oak

Trail)--OVER LAND. P.47

4)Based on

the present study, P. maculata can sustain travel over dry land for

more than 3.5 h at an average of 2 meters per hr, sometimes covering up to

3.5 m in less than an hour. p.49

5)This study has shown that the Louisiana invasive apple snail P.

maculata is well adapted for survival in the absence of water. It can

remain fully active under conditions of high RH, or it can aestivate

for long

periods if the humidity is low. The ability of P.

maculata to sustain travel over damp substrates and endure aerial

exposure suggests that the reduction of water levels is less likely to

be as effective as has been

reported for P. canaliculata. also p.49

Adult

Apple Snails are very strong, and make a lot of toxic eggs. It seems

like a grim situation, but there are allies already here in our

environment that may be able to keep the snails from overrunning

everything.

I've gathered images and video that I believe

illustrate some of the descriptions I've read, and they're below.

I have also put together an 8-minute long video that shows some

of the activities

I describe here. Here's the video link.

If anyone is curious about adult snails I've filmed--all of the

adult snails that I filme were removed from wherever they were found

and were

rendered unable to metabolize.

I

had revisited Scobee Field on 7/17/2021--between the two visits

described above. Although I shot the images shown below then (and

some video) I decided to read more to try

to put some perspective on

to what I had recorded. These are examples of the snails moving on

land. Other snail species can do this, but this species-Pomacea

maculata-is the destructive

invasive of concern. I found two

separate examples showing how snails could push through thick

vegetation and even leave a trail! The first two images below show one

of these trails,

and also how long it was. The rake is 15 inches

wide. Next is the snail, with scale to show size. The last image

shows the shallow "ditch" and the remaining water in it.

Snail

track in the grass. Rake =15 inches

There's the snail.

Snail is about 2.5 in (6cm)

Water in shallow ditch.

The

pictures below show other views of the same ditch. A snail was able to

deposit eggs on a single twig (that must have been interesting). Then

in that shallow puddle, I found

5

adult snails. Two of them are shown in the 3rd picture below, with a

closeup of one snail in the fourth picture. These pictures can be

compared with others taken before

and after this time (in sections above).

More of the ditch.

Lone egg mass on a twig.

Two snails in the shallow puddle.

Snail moving in shallow water.

The

first picture below shows egg masses on a tree surrounded by mud--many

feet from the water. The last three pictures show a different

track and the snail that made it.

There is water visible through the plants, but the snail is not submerged.

Egg masses on a tree, no water nearby.

Snail track through the plants.

The snail making the track.

Snail

moving over very shallow water.At Scobee Field on 7/24/2021--The

ditches dried, though the dirt was still damp. I noticed a snail shell

in a hole in the mud. Since I'd read about these snails can aestivate,

I took pictures of the shell before I moved anything. I had already

seen many snail shells lying out of the water in other locations, and

they'd all been empty(dead).

But just in case, I took many pictures of this one. The depression, or hole, or whatever, was intriguing.

Snail in the dried ditch

Shells of dead small snails litter the area

Snail in the hole shot with flash

Snail in the hole shot without flash

Then

I turned the shell over. The snail was alive! I could tell

by the sealed operculum. I took pictures of the snail and the

depression. The hole wasn't elaborate, but it seems

like the snail

made it. As of this date (9/29/2021) I haven't found any

description of how Pomacea aestivate naturally. Do they dig burrows, or

dig anything? I've read of

one experiment shows that it's possible for these snails to survive TEN MONTHS without water, as long as they can maintain a seal to converve internal moisture. The snail had

"backed into" the hole, so perhaps it could dig by manipulation of its foot.

Snail flipped over. It's alive!

Flipped snail next to the hole

Closer view of

the hole

Snail near the hole, view shifted a bit.

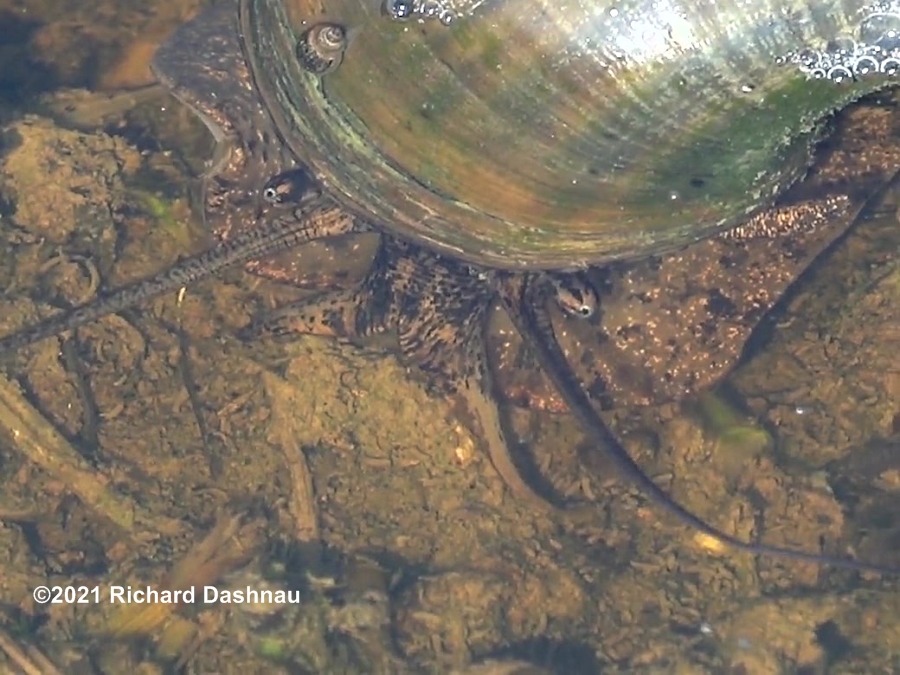

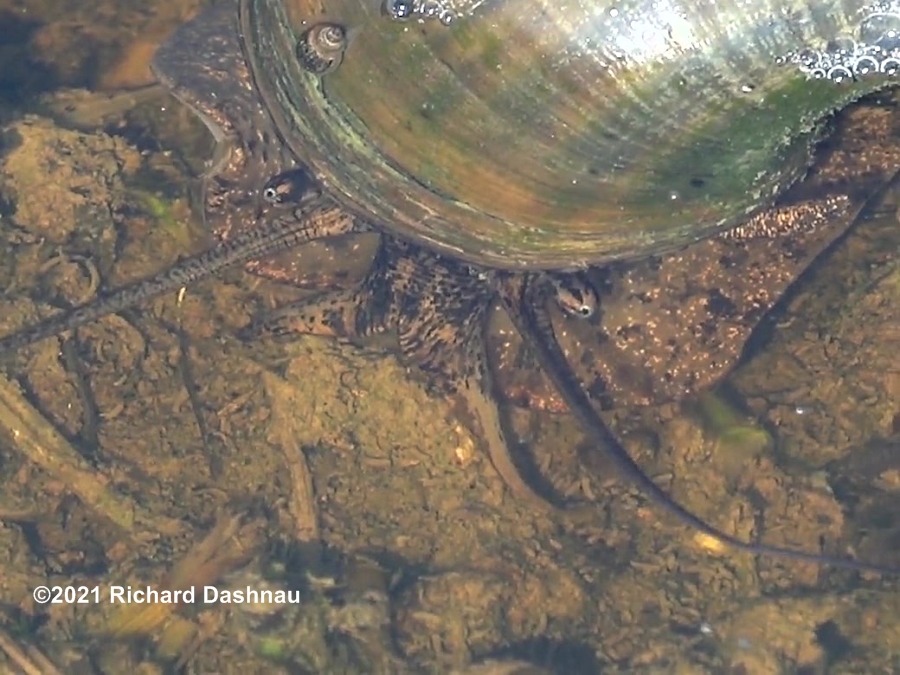

At Scobee Field on 8/17/2021--The

ditches had some water again. I found an adult snail moving around in

the water at one of the culverts. In this case, there were strings of

amphibian

eggs

in the water, too. I think they belonged to a species of toad.

I've read that Pomacea will consume amphibian eggs as well as the

various types of plants. So, I watched (and filmed) the

snail as it

moved around the ditch and over the eggs many times. I didn't see any

sign that this adult snail paid any attention to the eggs at all. The

snail didn't pause, the eggs remained intact.

The video clips I captured are included in the edited video. Here's the video link.

Snail in the ditch with amphibian eggs. 1 Snail in the ditch with amphibian eggs. 2

Snail in the ditch with amphibian eggs. 3

At Scobee Field on 9/18/2021--A small bit of water appeared in the

ditches. The pictures below show that the water hadn't been there long. But when I looked into that shallow

puddle, I found 5 adult snails. Where did they come from? How did they get there? I started filming, and this time I captured more interesting behavior.

Very

shallow puddle in the same ditch.

Live snails moving in the water!

The water hasn't

been there long. Two snails moving around mower tracks.

Apple Snails (and some other species of snails) have gills and

a lung. This explains why the snails can go over land, or climb

trees--etc. While I watched the snails moving around the

shallow

puddle I noticed them probing with their "siphon". But the probe

went straight up until it broke the surface of the water, where it

opened. The siphon had become a snorkel!

Pinched-closed siphon reached up. Pinched-closed siphon breached the surface.

Siphon begins to open.

Siphon opening expands.

Siphon is now a snorkel.

Siphon is now a snorkel.

Breathing through the snorkel.

Close the opening and submerge.

I

noticed something else while the snorkel was being used. With the

snorkel deployed, the head of the snail moved in and out; as if acting

like a pump. The series of images below

are frame grabs from

the video. They show how the head moved in and out. This is also

shown in the same edited video clip. Here's the video link.

Snail's eyes, antennae, and face.

"Air Pump" cycle, snorkel

up, head is out.

"Air Pump" cycle, snorkel up, head is in.

"Air Pump" cycle, snorkel up, head is out.

Although

these snails are pretty tough, there are already natural allies here

that may help control them--that is, help stop them from taking over

the environment. After all, they do

have a natural habitat

(continent of South America), and are part of the ecosystem there. So,

here are some of the animals on the Home Team:

1) Raccoons have been observed eating the adult snails--and they discard the toxic albumin glands. Here's a link to the article "Observations of Raccoon (Procyon lotor) Predation on the Invasive Maculata

Apple Snail (Pomacea maculata) in Southern Louisiana". And, here's a link to connected video showing raccoons with snails. The links were good when I used them. Can't guarantee they still are.

2)

Remains of Apple Snails have been found in stomach contents of

alligators harvested in Louisiana. In article "ALLIGATOR

MISSISSIPPIENSIS (American Alligator). NOVEL NON-NATIVE PREY".

Link to the article (in Herpetological Review, pages 627-628).

3)

At least one native species of ant will attack snail egg masses.

Surprise!! Not fire ants (although they might consider it). Article:

"Observations of Acrobat Ants (Crematogaster sp.) Preying on the

Eggs

of the Invasive Giant Applesnail (Pomacea maculata)" Link to the article is here. Link to a related video is here.

4) A native sunfish--Redear Sunfish (Lepomis microlophus) AKA "shellcracker" is known to eat small snails of many kinds, including young Pomacea. TPWD link here.

5)

Limpkins! These birds are not native here, but have moved in to

Texas, at least for the summer, and they are specialists in eating

Apple Snails. As far as I know, Limpkins have not been seen nesting

here yet, so they might not have established a population here--so far.

6)

Crawfish. Some crawfish are voracious. Native Red Swamp

Crawfish (Procambarus clarkii) are for sure, and I've read that they

will also eat young Pomacea. Which is good, since I've also read that

adult

Pomacea snails can ravage crawfish habitat and also eat their young. So

that's a few of the animals that can help control the growth of Apple

Snail populations. Along with these...are people. Scientists

around

the world have been trying create some kind of control but have not yet

found one. In the meantime, collecting and destroying adult snails, and

scraping snail eggs off and into the water can help. I have

done

a bit of this at Scobee (removed about...70 snails total

and maybe a hundred or so egg masses I think). And also at Brazos

Bend State Park (only found about 20 snails, but have removed about 400

egg masses off

the trees along Live Oak Trail there.) This is

not much compared to the efforts of some other groups of people at some

other ponds and lakes. The images below are from Brazos Bend State Park

on 09/05/2021.

They will give some idea of the number of masses

possible on the trail. I've found 180 masses along a 100-yard stretch

in two hours. A short video demonstration of scraping technique is in the same edited video.

7 egg masses, with old smears others.

4 egg masses, with old smears others.

4 egg masses, maybe different species

9 egg masses, with old smears from others

5 egg masses, from the picture of 9 13 egg masses, with old smears from others

12 egg masses, with old smears from others

Scraping with paint roller handle step 1

Scraping with paint roller handle step 2 Scraping with paint roller handle step 3

Scraping with paint roller handle step 4

Rinsing toxic egg goo off of scraper.

Go back to my home page, Welcome

to rickubis.com

Go to the RICKUBISCAM page.