Limpkins! (Aramus

guarauna)

This page started 04/01/2022

from material I posted earlier on other pages. Rickubis

designed it. (such as it is.) Last update: 11/15/2024

Images and contents on this

page copyright ©2021- 2024 Richard M. Dashnau

Go back to my

home page, Welcome to

rickubis.com

Go back to the RICKUBISCAM

page.

I

was introduced to Limpkins when I heard about their appearance at Brazos

Bend State Park. I learned that they probably followed the invasion of

Apple Snails (Pomacea sp.)

across the Southwest states until they appeared in Texas. I learned about

and saw Apple Snails first, and the information I've gathered about them

is on my Snails Page.

I've

learned that although the circumstances which brought the Limpkins here

isn't so good (invasive snails), the fact that we can watch them in

different places, here in Texas, is

really amazing. It appears

the Limpkins have only been here a few years so far. So, I'm collecting my

images/videos here so others can see them. The latest additions will

be at the top of the page.

11/03/2024

At

BBSP, while

walking on the

Spillway

Bridge around

8:30am; I'd

been hearing

Limpkins

calling to the

South. But

they were far

away, and out

of sight. I'd

stopped

on the

bridge to just

look around.

The view to

the South now

shows parts of

the "mile

stretch"

section of the

road--which

hadn't been

visible until

recently. After

seeing a

Spoonbill. I

finally found

one of the

Limpkins about

40 minutes

later. I

was still on

the bridge,

because it was

a nice

morning. The

Limpkin was

even further

away than the

Spoonbill was.

But I tried

some photos

for that, too.

It was to my

left, or

Southeast of

my position,

at 9am. I was

looking almost

towards the

Sun, and it

brightened the

outline

of the

Limpkin. This

was just the

second weekend

that I'd heard

Limpkins in

the park after

a year

or so.

The last 3

summers have

been brutally

dry. Hurricane

Beryl and the

rain a week

after

helped

replenish some

of the water

we needed. The

presence of

the Limpkins

was a

good sign.

03/19/2023

A cold front had passed through

recently. That morning, the thermometer in my car showed 47°F. I didn't

bother trying to record the

air

temperature on the trail because I was

trying a new piece of equipment that I thought would give me

related data. I can say that it felt REALLY cold out there.

Limpkins

were

first reported in Texas in 2021. They've been hunting

in Brazos Bend State Park since then, usually around Live

Oak Trail (and the property next door) during the Summer.

When

Live

Oak Trail dried out last year, the Limpkins stayed near

the

lake next door to BBSP, but a few foraged in Elm

Lake.-which is about 1/2 mile from where the Limpkins were

on Live Oak Trail.

I've

watched them in this corner of the lake, and found out

they were eating mussels.

Limpkins

are "mollusk specialists", and are adept at opening many types

of shells. I was happy the first time I got to see a Limpkin

eat a mussel a few weeks ago. On this day, I watched

this

Limpkin capture at least

6

mussels over 45 minutes, and was able catch some of that on

video. That's what will show here. The Limpkin was

hunting along the near bank of that island across

the way (about 50 yards

from

this trail). When the Limpkins hunted along Live Oak Trail,

they probed with their beaks, similar to the way Ibises do.

It seemed to be mostly blind probing in

murky water with dense vegetation. But this one seemed to be

hunting with its eyes, visually inspecting the water, similar

to Herons or Egrets. the frequent probing at Live

Oak Trail. Pictures

and video clips of the Limpkins on Live Oak Trail are on

further down on this page.

I

caught multiple videos of the entire process-from capture to

cleaning the last morsels out of the shell. The procedure as I

saw it: 1)Hammering at the mussel-this seems to be aimed

at the

outer edges of the closed shell, possibly to chip off

the edge so the beak can be pushed in. 2)Standing the shell

and trying to push the beak between the halves. 3) Once part

of the beak is in,

move it around to disrupt the mussel until both jaws get in so

that the shell-closing muscles can be cut. 4) Now the mussel

shell lies open. Time to snip the good parts away from

the shell.

Small bits are pulled from the shell and tossed, although a

few are swallowed. 5) The main body is pulled out, shaken a

bit, then swallowed without ceremony. 6) A bit more

cleanup of the shell

and surrounding to pick up any missed scraps, and then off to

hunt for the next one. Someday I might pull frames from

the video to illustrate that procedure here, but not today.

For now, it's

visible in the edited video. By the way, note

all of the discarded mussel shells in a few of the pictures

below. Wow! So, even though the day was cold, damp, gray

and pretty miserable-it was

worth going out on the trails that day.

On 01/15/2023 I was at BBSP, and it was an

interesting day. Herons and limpkins! At

11:00, one of the park visitors pointed out that a Limpkin (Aramus guarauna) was

foraging near an

island in Elm Lake.

I'd

have never noticed it otherwise, since a group of

Black-bellied Whistling Ducks were lying around and swimming

there, and the Limpkin was among them.

The Limpkins had been hunting along Live Oak Trail through

2021 and 2022.

They seemed to leave that area during drought in the Summer

of 2022, and one was seen briefly in Elm Lake then.

I was happy to see this one, and wondered if it would get

lucky, since they prefer to eat molluscs. The Limpkins

have moved into Texas because of large numbers of Apple

Snails (Pomacea sp.)

that have appeared here. To our knowledge, there are still

no Apple Snails in Elm Lake (no egg cases visible).

But the one seen in Elm Lake in 2022 was eating

mussels. And...this Limpkin

found a freshwater mussel, too!

The Limpkin's meal remained partially hidden by a bump in

the ground. I was happy to see the process anyway. The

images below are frames from video.

The

edited video is here .

From

BBSP on 05/29/2022

For now, more Limpkins. As usual, lots of things were

going on out at the park. I spent about an hour on Live Oak

trail, and watched

the Limpkins. Conditions along that trail have been getting dry

over the last few weeks, so the Limpkins were foraging at least

25 yards away from me--although they were North of the

trail. That is, between Live Oak Trail and the Park Road.

This video link will let the viewer spend

about 4 minutes with some of the Limpkins I saw.

As noted elsewhere on my pages,

during dry times Apple Snails (Pomacea sp.) can aestivate by

burrowin into the mud. One study showed that they could live

that way for 10

months.

One of the snails that was retrieved by a Limpkin was

covered with mud (I didn't recognize it was a snail at first).

Perhaps it had been trying to burrow. No--not the one in

the image below.

On 4/10/2022,

I'd signed up to lead a hike and other tasks, so I went out to

LIve Oak Trail early to look for Limpkins. I got to watch some,

and here are

the images. I still haven't caught close shots of Limpkins

dissecting snails, but there is some of that shown at distance

in the video I got. There are also a few closeups of the

Limpkins'--and

Ibis'--dipping behavior while foraging.

I believe that "dissection" is an appropriate term for what the

Limpkin is doing to the snail. When viewed in realtime,

movements are so quick, that

the quick twisting and flicking doesn't reveal what is

happening. But if the video is slowed down, then it's possible

to see that the Limpkin is using its beak with precision, and is

tweezing

away small bits of snail flesh, and then tossing them aside. In

the slowed video, some of the bits are visible, and some may be

pink. I believe that the Limpkin is rejecting bits based on how

they taste. In the video I captured, bits were snipped and

tossed...until one bit was pulled off and eaten. The rest of the

carcass was eaten right after that.

The edited video is at this link.

Also, if pictures of one

Limpkin is good--then a picture of two Limpkins must be better!

So, they're here, too.

Many folks

describe a Limpkin as being about the size of an Ibis. Today,

a White Ibis (Eudocimus

albus) foraged

next to a LImpkin, so I got some direct comparisons. The two

birds foraged

next to each other, and I could watch them both probing for

food with their beaks. Clips of them foraging together

are also in the edited video.

From BBSP on 04/03/2022.

More with the Limpkins! I was on Live Oak trail

around 8:30am. There weren't very many Limpkins active there

yet, but I did see a few.

One was calling from a

tree across the lake that is outside the Southern boundary

of BBSP. I shot video of that to show how far that sound

carries. About 30 minutes later, The

Sun started

breaking through the

clouds, and more Limpkins began hunting North of the

trail. I was briefly distracted by watching a Great Blue

Heron hunting successfully, but returned to the Limpkins

for these images and

video. The images below are a mixture of still photos

and frame grabs from the video clips. The video clip is here.

I was able to

get some nice close views of Limpkins hunting, but a clear

view of the Limpkins breaking into the snail still eluded me.

I also found this report on line:

"Natural selection by

avian predators on size and color of a freshwater snail

(Pomacea Jagellata)" 1999 by Wendy L. Reed and Fredric J.

Janzen. The research was done in Costa Rica,

but involved Snail

Kites and Limpkins. The predation was on Apple Snails, but a

different species. Size and behavior of the snails seems to

be the same as our problem P. maculata though.

Among points in the

report I found interesting: 1) Snail

kites rely on visual cues while hunting by

flying slowly across a marsh or hovering while searching for

snails. Limpkins rely on tactile cues

during foraging

by probing beneath vegetation and on the bottoms of marshes

for apple snails. 2) Individual Limpkins differed in the

size of snails they consumed, and in their choosing to

puncture shells before

consuming snails. No single foraging pattern is

exhibited by all Limpkins in this study area. 3) As snails

age and grow, they change their vertical distribution their

primary

behavioral defense

against predators. Large apple snails spend more time at the

water's surface. The change in size is accompanied by

changes in behavior. Larger snails respond to

mechanical

disturbances by dropping off vegetation and burying

themselves in the substrate quicker than small snails do.

4) Limpkins may prefer snails of average size

due to decreasing

energy gains at either

end of the snail size distribution. Limpkins were more

likely to puncture shells of large snails compared shells of

small snails. This shell-puncturing behavior suggests

that large snails may

be more difficult to handle, requiring additional time and

energy to puncture the shell and obtain a meal. The optimal

prey size for Limpkins might then be those snails small

enough not to

require a hole to procure a meal, but large enough to

provide a worthwhile effort.

The report added a bit more perspective to some of behavior

I've recorded. I can see how a Limpkin might have a

harder time "pincering" a large snail in its beak and carrying

it, so puncturing

it would make it easier to carry. But I've seen that the

Limpkins have carried the shell out of the water and to a

solid base to give support the snail shell during the stabbing

attack. I think piercing

the snail weakens it and the muscles holding the operculum

closed, and allows the Limpkin to get under that "trap door"

to tear it off. In one of the other clips from this day,

I show what happens

with a really small snail (three images below right).

The Limpkin set it down, prodded it a bit (and it was

too small to get a beak tip into) then tried to smash the

snail with the tip of its beak. The

snail was knocked into the air and fell in the water and was

lost to the Limpkin.

A

bit later, the Limpkin found a larger snail. The snail was

carried to a more solid platform. .

I

could see the Limpkin working on the hidden snail. It

alternated delicate probing with hard stabbing.

Movements changed as the snail's body was exposed. There

was vigorous rapid movenents

of the beak as the snail body was pulled free. Viewed in

realtime, the movements are very quick, and barely noticeable,

but with slowed down video, the amount of movement is

impressive.

What was being shaken free? Was it shell fragments,

detritus, maybe the toxic yolk glands? I can't identify the

fragment the seemed to fly off the snail as it was being

shaken.. The Limpkin

didn't immediately swallow the snail either. It tossed the

meat to the back of its beak, seemed about to swallow--then

spit it up and shook it a few more times before swallowing

it. Finally, I

caught a quick view of a Nutria "photo bombing" the scene.

Again,

The

video clip is here.

Update 04/01/2022 - From BBSP on

03/27/2022. I'd

last seen Limpkins on Live Oak trail last October (2021).

Since then, less Apple Snails (Pomacea maculata) and egg

masses were

observed on or near the trail. Over the winter, no snail

eggs appeared on Live Oak Trail so I stopped going there

because I thought the Limpkins wouldn't be

active. Sometimes I could

still hear Limpkins calling from this area even while I was at

40 Acre Lake. The lake just

across the South park boundary contains the main snail

infestation. With the warmer weather,

I checked the trail for snail eggs. No egg masses yet,

but the Limpkins were around. Two Limpkins were resting

on top of the floating plant mats about 40 yards away, along

with a few

scattered snail shells. I watched another one as it

hunted. This was the first time I got to see the

Limpkins foraging! Widely-splayed toes help distribute the

Limpkins' weight as they stride on

floating plants. Their constant probing for prey

reminded me of the similar behavior of Ibises. Success!

Jackpot! A big snail was discovered as turtles and I watched.

The Limpkin moved to a firm

surface so it could pierce the snail. It placed the snail,

then attacked it with short, accurate and powerful strikes.

Most of the images here are frames from the video clips I

shot.

The video clip is here.

I've tried to

pierce Apple Snails by stabbing them with the point of a

smooth flounder gig. The shell is round and hard--and

difficult to pierce with a single point. If the point wasn't

thrust just right,

it slid off the shell, and the snail rolled away. But

this Limpkin was an expert, and pierced the shell after a

handful of hits. I was not close to the Limpkin, so

couldn't get a great view of its technique.

There's a a bit of manipulation needed to get the snail out of

the shell. It's interesting that the feeding strategy

doesn't include shattering the shell into pieces. There

was rapid back and forth

head-twisting motion, just before the snail is taken out. And

then the end of an invasive snail.

Even

with

wide feet, the Limpkin was too heavy for some plant mats. It

continued working as it sank into the water, then hopped to

the next mat. I saw this Limpkin eat at least 5 snails

in 30

minutes. The probing seems to be random. How can a

Limpkin tell when it has found a snail? It must be contacting

other hidden objects, sticks, etc., with its beak. But

it seemed to ignore

them in these very quick contact probes. But with

positive snail contact, the Limpkin starts working at the

snail. One snail took more effort, and the Limpkin

had to do a lot of twisting to get it

out of the plants. What was the snail holding on to? The

Limpkin seemed to be a bit surprised,. Again, The video clip is here.

The

egg

masses of Apple Snails (Pomacea sp.) are toxic. The

glands that provision the snail eggs (albumin glands) inside

the snail are also toxic.(more details are on my

Pomacea Page).

There are multiple reports that describe how the snails'

predators discard these glands. ( since Oct. 2021 I've found

more reports that describe this behavior) Discarded glands

have been

seen in snail detritus left by Raccoons. (Observations of

Raccoon (Procyon lotor) Predation on the Invasive Maculata

Apple Snail (Pomacea maculata) in Southern Louisiana by

J. Carter et. al (page N15.)

Removal of these glands by Limpkins is mentioned in " Defenses

of the Florida Apple Snail Pomacea

paludosa by Noel F. R. Snyder and Helen A. Snyder

(1971)(page 177)" and by Snail Kites in

"Mollusk Predation by Snail Kites in Columbia Noel F. R.

Snyder and Herbert W. Kale" 1982 (page 97)

Nothing pink showed in the meals I watched, but that is

inconclusive. They could have been hidden inside the

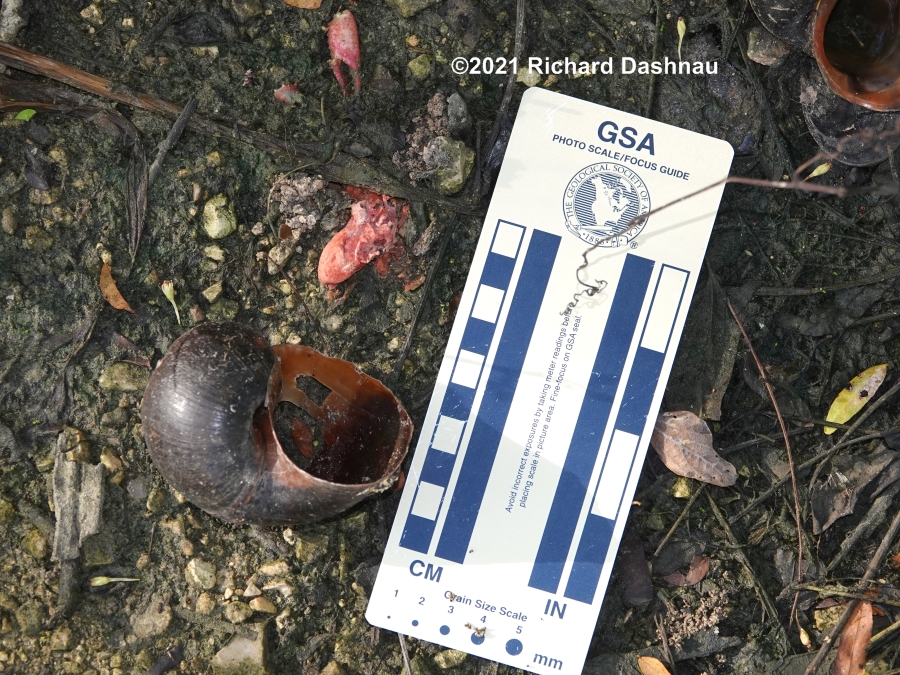

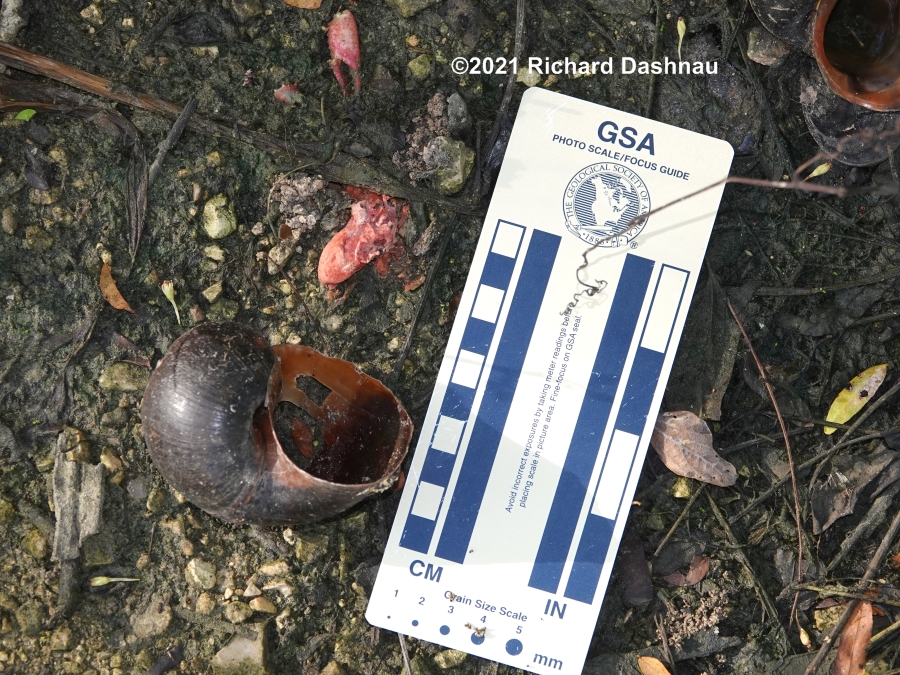

body. I took the last picture on Live Oak trail in

2021. The shell shows twin punctures,

which are evidence of Limpkin predation. The pink mass above

the shell is a discarded albumin gland. I hope to catch

this behavior on film.

The snails are still here in the park. It was great to finally

see Limpkins hunting; but bad news that there are so

many snails inside BBSP.

Update 04/04/2022 - From BBSP on

10/24/2021. On

Live Oak trail October 2021. I was still trying to see

more Limpkins, and hoped to see them foraging. I also hoped to

see any other

animals-Alligators, or Raccoons-going after the Apple Snails,

but no luck there. I did see and hear this Limpkin, and

the call was not the "crying" sound that I'd hear before. I

recorded the call.

Since then, I've learned that Limpkins have different calls

(like other birds do) and this was probably a female Limpkin.

I got the call on video, and The video clip is here.

07/25/2021 and

08/01/21-

I've

been

doing more research on our apple snail invaders since July. When I saw

the inside of an adult Pomacea, I noticed orange masses or organs.

I figured that those were eggs. Since the deposited egg masses are

toxic, I wondered if the eggs inside the snail were also toxic. And, if

the eggs are toxic--how can any animals

--such as Limpkins--eat the adult snails? After a lot of

searching, I couldn't find any detailed description of how this

situation is dealt with. The first picture below was

taken on 7/24/21, but I'd seen inside other snails before then.

The other two pictures were taken 7/10/21, and show a snail that

something had eaten. At the time, I hadn't

realized that the toxic egg masses had been left inside the shell.

I found a number of

references saying that animals that eat the snails discard the albumen

glands. But the only predator I saw named

doing this was Snail Kites. But no clear descriptions.

I started searching for proof that Limpkins

might discard these organs. I found a video on youtube that shows a

Limpkin doing this! After that, I started looking around BBSP for

signs

of this behavior.

But let's pause a bit. Limpkins? Limpkins (Aramus guarauna)

are long-necked wading birds with long, pointed beaks. They're about the

size of Night Herons (maybe a bit larger).

According to Avibase, the World Bird Database, it is the only extant species

in the genus Aramus and the family Aramidae. The "home range" of 4

subspecies of Limpkins is: Florida, Cuba,

Jamaica ; southern Mexico south to western Panama;

Hispaniola and Puerto Rico; central and eastern Panama; South America,

south west of the Andes to western Ecuador, and east of the Andes

south to northern Argentina. Like many wading birds, Limpkins can be

generalist predators but according to many sources, the greatest

component of their diet is: Apple Snails. If we examine the

list of regions in their "home range", we can see something

missing-- TEXAS.

That's

right. In fact, their home range is far

from Texas.

Texas is now being invaded by Apple Snails. If only Limpkins were

in Texas! Well...they ARE in Texas. In fact, they have been

hanging around in the lake next door to BBSP for some months

now.

That lake is infested with snails. Unfortunately, the snails have made

their way to the BBSP side of the fence, along Live Oak Trail. But the

Limpkins have been picking them off there, also.

Discarded snail shells litter the trail. I went down Live Oak Trail on

7/18, and I saw something interesting among some discarded shells. I

took a few pictures. Next to one

of the shells is a pink mass. I think that mass is one of the "albumen

glands" that was discarded by the Limpkin that ate that snail. The trail

was really wet, so I didn't go further.

First 3 images below show shells on the trail, and a pink mass neer

them. The last image was taken there on 8/1/21, and shows pink material

in the discarded shell.

I returned to Live

Oak Trail the next week (7/25). I'd been around the other trails,

and entered Live Oak from the East end and walked West. I was

doing snail egg removal. It was Noon,

and it was hot, so I didn't expect to see anything. A Limpkin

appeared on the South side of the trail, near the fence, and hunted the

area near the fence. I stayed back, and hardly moved.

It came to the trail, walked on it a bit, then went back under the fence

and eventually up the levee and across. I got pictures and a bit

of video! This is all edited into this video.

Next weekend

(8./01). I'd been out on the other trails first. I met a couple park

visitors I'd sent to Live Oak trail and they told me they'd hadn't seen

any Limpkins, but had seen snail egg masses,

and even a few live snails. So I was on Live Oak Trail again, at

about 12:30pm. I'd gotten almost to one of the "bridges" when I

saw a Limpkin up in a tree between the trail and the

road--that is, North of the trail. I watched it for about 20 minutes,

until thunder from approaching rain clouds convinced me to start back to

my car. I got a brief look at another Limpkin

in a tree near the one I'd been watching. They both moved, and

seemed to start hunting, but I didn't want to get caught in rain that

seemed to be approaching. I got photos and video

clips. Again, this has all been edited into this video.

And, I found

another snail shell that seemed to have remnants of a discarded "albumen

gland" in it. I also found another paper that seems to have been

inspired by the habit of snail predators

discarding the "albumen gland": "Apple

Snail Perivitellin Precursor Properties Help Explain Predators’

Feeding Behavior" 2016 by Cadierno, Dreon, Heras. While it

discusses Pomacea canaliculata and

not our problem (P. maculata), I think it's still related. This

study is where I got the term "albumen gland" for the organ which

produces the snail eggs. Perivitellin

serves as a nutrition source for snail

embryos (similar function to egg yolk ). While the paper is a bit

technical for me to fully understand, for me it verified: a)

that the organs are

toxic, and therefore consumption of the entire snail

could be dangerous; b) that experienced predators do

discard toxic parts of the snail, rendering it safe to eat. From the

paper: " Therefore, as the noxious

perivitellin precursors are exclusively

confined within the AG, this

explains why it is the only usually discarded organ, even when this

behavior implies a large loss of the total energy and nutrients

available from the soft-body biomass

(Estoy et al. 2002). Finally, we

propose that the reddish-pink gland color may contribute to this

behavior, helping the visual-hunting predators of adult snails to

associate the bright AG color with the

noxious compounds it carries."(page

466 "AG"=albumen gland) This could be trouble for our

local predators (such as alligators) that might consume entire

snails. Raccoons might be able to identify

and remove the glands, but they'd have to learn about the danger first

(that might be what ate the snail in the picture above). It's

potentially good news that Limpkins are eating snails here. It will

be better news if they establish a breeding population in Texas. They

can help control the spread of the Pomacea. But, regardless of

predation, and it seems to me that the snails will remain. I think

the most we can hope for is that the predators that have followed the

snails (and other local predators) and the snails will reach a "balance"

where the snails will not overpower the environment.

There must be reasons why Limpkins haven't made the journey here before.

If lack of snails was a factor...where they're here now.

But, if there are other environmental reasons (such as temperature)

the Limpkins may not stay. I hope they do.

Go back to my home page, Welcome to rickubis.com

Go to the RICKUBISCAM

page.