ICHNOLOGY-the study of animal traces

(tracks,

burrows, etc.) Page 2

This

page was born 06/12/2023. Rickubis designed it.

(split it off from an older page.) Last update: 03/23/2024

Images

and contents on this page copyright ©2001-2024

Richard M. Dashnau

Go to

Ichnology

page 1.

Go to Ichnology

page 3

Go to Ichnology

page 4 (this has the most recent observations).

Go

back to my home page, Welcome

to

rickubis.com

Go

back to the RICKUBISCAM

page.

----------------------------------

That's

me on the 40-Acre Lake Trail at Brazos Bend State Park

(12/31/2007). I

was waiting for an otter to show up. It didn't.

Over the

years that I've been keeping these pages,

making new observations and learning new things, I have met

some

interesting people.

Two

of them are Dr. Anthony Martin and Dr. Lisa Buckley.

They study ichnology--

animal

traces. While the term is commonly used in relation to

fossils

(such as dinosaur tracks), it also applies to living creatures

as well

(sometimes called "neoichnology"

with "paleoichnology" for fossils). One major

aspect of this study is that such traces can show animal behavior.

For instance, a single footprint might not say much,

except

what

kind of animal made it; but a series them might tell if

the

animal

was running, or jumping etc. There are three basic

factors

that

help to interpret traces: A) Substrate (the

material that holds the

trace) ; B) Anatomy (the part of the animal that affected the

substrate) and C) Behavior (what the animal was doing with the

anatomy

that affected the

substrate). (see "The Three Pillars of

Ichnologic Wisdom" page 9 in Life Traces of the Georgia

Coast

by

Anthony J. Martin) I admit that I am not very good at

finding

and

interpreting

such traces. But, it is still fun to look and try to piece

together the

mystery of what transpired at that spot before I got there.

I

usually capture images of animals

activity. But every now and

then I've taken pictures of traces. I'll begin

collecting

them

here. I will eventually arrange them in chronogical

order of

some

kind. Many, many

thanks to Dr. Martin and Dr. Buckley for many

conversations via email and online; and for being supportive

of my

amateurish efforts.

One

more

thing: Although alligator burrows (or dens) and nests would be

considered ichnological traces. I've only got one example of

an

alligator den on this page. I have

many observations of alligator dens, and have already gathered

them onto other

pages, starting here.

This page is arranged with the newest entries at the top.

At

Scobee Field on 10/16/2021

I found this burrow, and it had water in it. I had a brief

view

of something moving in the hole, and took some pictures of a

crawfish's

face before it submerged

but they didn't come out very well.

But at least I knew that the hole belonged to a crawfish. For

the next

40 minutes, I stalked the hole, and caught some pictures and

short

video

of the crawfish. From the size and color (and location) I assume

that

this was a Red Swamp Crawfish (Procambarus clarkii). Even though

the

burrow was in a ditch,

there was no chimney, but if there was one, it had probably been

crushed by the machinery that left tracks in the mud.

I

read a lot of literature about this species of crawfish. There

are

descriptions of their physiology and their tunneling

behavior. In "Burrowing activity of Procambarus

clarkii

on levees: analyzing behavior and burrow structure" by Phillip

J.

Haubrock . Alberto F. Inghilesi . Giuseppe Mazza . Michele

Bendoni .

Luca Solari . Elena Tricarico (2019)

I found a brief reference

to "the typical sideway position used in this species to breathe

air

oxygen outside the water" .

In "Procambarid Crawfish: Life History and Biology W. Ray

McClain and Robert P. Romaire (2007)

"For

unknown reasons, some individuals will not burrow as the habitat

dries,

while others will construct very shallow burrows that can

quickly dry

out and lead to death." "Crawfish burrows

are usually

dug by an individual crawfish, with the burrow diameter

determined by

the size of the crawfish. The burrow extends downward into a

terminal

chamber that is slightly larger than

the diameter of the

tunnel." "it is thought that any free water in a burrow is

likely to be

trapped water, perhaps from rainfall seepage, rather than water

seeping

into the burrow from the water

table. When there is no standing water in the burrow, wet

mud

in the chamber serves as a humidifier."

In

"Gill

Morphology in the Red Swamp Freshwater Crayfish Procambarus

clarkii (Crustacea: Decapoda: Cambarids) (Girard 1852) from the

River

Nile and its Branches in Egypt: by

Mohamed M. Abumandour

(2016) describes: " From available literature, it is well known

that

there were special anatomical characters of the respiratory

adaptations

of crustacea to

terrestrial and amphibious life, in which the

crayfish can live for weeks in burrows without free water and

adapt to

survive for long periods of hypoxia that occur within this

burrows due

to the

large surface of respiratory gill area." The crawfish

exposed its side to the air, in a "breathing posture". In

the

closeup, there are feathery structures visible at lower edge of

the

carapace,

where the legs are attached. I think these are

sections of the gills, specifically the "podobranchiae" one of

three

types of gill structures possessed by crawfish. ("The red swamp

freshwater

crayfish possess a trichobranchiate gill type, which

consists of three types according to their place of attachment

on the

body; podobranchiae, arthrobranchiae and pleurobranchiae." from

Abumnador

2016). With such an abundance of gill tissue, crawfish can move

around

in air for some time-as long as the gills are kept moist.

I

had to walk away from the burrow, then move back slowly, and

then use

telephoto shots to catch the crawfish unawares. I got a few

shots of

its face before it backed under the water.

These

pictures of Scobee

Field from 10/02/2021-- 10/09/2021 show how the water levels

can change at the park. Since Scobee Field is inside

Barker

Reservoir, it is going to flood if we

get

enough rain. After all, Barker Reservoir was built to collect

water and

control it to avoid flooding Houston, which is East of this

area.

10/02/2021

10/02/2021

10/05/2021

10/05/2021

10/09/2021

10/09/2021

At

Scobee Field on 9/25/2021--

inside of Barker Reservoir .This time, I

investigated

one of the larger holes. This one was about 2.5 inches diameter.

When

I

tried to get pictures of the inside, I found a cricket, but

obviously

that was just borrowing the hole. I used a folding ruler to

measure the depth, and had to bend the ruler slightly.

Multiple

samples got me a

burrow length of 13 inches. The

sides of the burrow were worm smooth, and dry. The

cricket

had already demonstrated that the walls were good climbing

surfaces.

I

decided to try to fill the burrow with water, to see if I was

looking at a hole, or a tunnel. I found a discarded 32 oz cup. I

could

only fill it about halfway because of the water fountain. I

filled the

hole, using 3 "half cups", so maybe a quart and a

half.

I did fill

the hole, though, so it appeared to be closed at the end. It

emptied

slowly, so water did seep

out from somewhere. After about 3 minutes, when the

level dropped

4 inches I refilled

the hole, and then watched to see if anything would

come out. I

expected a crawfish, even though the opening was about 2x larger

than

most crawfish burrows I've seen. This time it took

about 10

minutes to go down 4 inches. Refilled again--12:06

The water level dropped slower.

Then,

about 12:12 (6 minutes

after filled), I got a surprise. A Gulf Coast Ribbon Snake

(Thamnophis proximus) poked its head out of the

water. I stood still

and

watched as it checked

to see if the coast was clear. It went back

under the

water...then came back up. I stayed and watched. I stayed

motionless as the snake slowly crawled out of the hole. It

stopped once

to "yawn", or maybe to readjust its jaws.

I

felt a bit sorry, since I'd flooded the snake's hiding

place-although I

hadn't known it was in there-because I didn't know where it

could

go. There

was little cover around

that ditch.

The

snake

decided

it was safe to move. It got out of the hole, and

then...disappeared under the grass. I was totally surprised at

how

easily it disappeared! I never did find out what

might

have made the hole. I thought that it might have

been a snail's

burrow, and had slight hope that it might come out, it didn't

happen

before I left.

I

tried a little geometry to figure out the size of the hole,

by using

the formula for the volume of a cylinder: V = πr²h

Hole diameter was 2.5 inches so radius = 1.25

Depth was

approximately 13 inches. So: V =

πr²h

3.14159*(1.25*1.25)13

= 63.813 cu.in. BUT the

measured volume was

1.5 quarts = 86.625 cu in

So I did this: 86.625 =

3.14159(1.25*1.25)h and 86.625 = 4.9 *h and

86.625/4.9 =h

and 17.689 = h so the hole should have been

about

17 inches

long (or deep?)

This really doesn't tell me much since I got a

4-inch difference, and can't be sure if the burrow is

symmetrical,

anyway. But it was a fun exercise.

At Scobee

Field on 8/28/2021--The

Scobee Radio Control Flying Field is inside of Barker

Reservoir. It's

about 4 miles West of Fiorenza Park North. The airfield is

within a 65

acre rectangle

(Google

map measurement). There's an 8-acre picnic

area around the main parking lot. Most of the time, this

area is dry;

but sometimes water covers the entire area. I'd started

paying

more

attention

to

the ditches and wet ecology when I learned about apple

snails

(Pomacea maculata); and had found them at Scobee.

While

walking the ditches, I saw many burrows about 1 inches

across which I

assumed to belong to crawfish. But there were also other

burrows that

were about larger--maybe 3 inches across.

During

that time, I

also learned that Apple Snail can burrow to avoid adverse

conditions,

and I wondered if the larger burrows could have been made

somehow by

the snails. By the way, although

I

have found occasional

mention of the snails burrowing, I can't find any pictures,

or

diagrams, or descriptions of what the burrows look like. I

*did* find

what seemed to be snails that had made

very

shallow holes-maybe the

beginnings of burrows-but that's all. At various times

through the

summer, I examined some of the burrows in the dried ditches.

Here are

some of them.

A pair

of holes in the dry ditch

Closer view of the holes

I would call these "crawfish

sized" holes

I tried a depth measurement.

About 8 inches deep.

I could see the ruler from the other

hole. These

holes

showed excavation

traces

About

1 1/2 inches across.

I checked one more large

hole...

....and

this occupant came up

to see me.

I've seen holes dug by toad

before...

...but the toad could have

borrowed it.

At Scobee

Field on 9/18/2021--This

time I found a fresh hole. The ground was soaked well, so

the mud was

soft, and didn't mold into solid pellets for making a

chimney. But I was

able to

get

a quick look at the crawfish's mud-covered face in the hole

before it

dropped out of sight.

At Scobee

Field on 7/24/2021--The

ditches dried, though the dirt was still damp. I noticed a

snail shell

in a hole in the mud. Since I'd read about these snails can

aestivate,

I

took pictures of the shell before I moved anything. I had

already

seen many snail shells lying out of the water in other

locations, and

they'd all been empty(dead).

But

just in case, I took many pictures of this one. The

depression, or

hole, or whatever, was intriguing.

Snail in the dried ditch

Shells of dead small snails litter the area

Snail in the hole

shot with flash

Snail

in the hole shot

without flash

Then

I turned the shell over. The snail was alive! I

could tell

by the sealed operculum. I took pictures of the snail

and the

depression. The hole wasn't elaborate, but it seems

like

the snail

made it. As of this date (9/29/2021) I haven't found

any

description of how Pomacea aestivate naturally. Do they dig

burrows, or

dig anything? I've read of

one

experiment shows that it's possible for these snails to

survive TEN

MONTHS

without

water,

as long as they can maintain a seal to conserve internal

moisture. The snail had

"backed

into" the hole, so perhaps it could dig by manipulation of

its foot.

Snail flipped over. It's

alive!

Flipped snail next to the

hole

Closer view of

the hole

Snail near the hole,

view shifted a bit.

07/19/2021-

I

haven't been able to exercise in the area I normally use because it's

been raining. Today, it seemed like the circle had dried

enough

to use,

so I walked around it, clearing sticks and other items.

As I made another circuit, I noticed a round hole.

It was

about 1.5 inches (3.8 cm)across. It was much

too large to be a

cicada exit burrow. My first thought was that it had been a crawfish

burrow (Red Swamp Crawfish Procambarus clarkii) that had had

the

"chimney"

knocked off--perhaps by park mowers. I wasn't wearing my

glasses,

but as I stood above the hole and looked down, I thought there was

something

in there. I retrieved my glasses and a camera from my car,

and returned.

I

stood above the hole, this time wearing my glasses. I bent

and

looked down into it...and something moved. Then, a face

appeared

at the opening! It was a toad!

The little face looked up at me. I'm pretty sure that the

toad made that hole--probably as the water dried and of

course before the mud had hardened. I took

a few more pictures--giving the toad space so I didn't scare it.

Then, I moved my workout to the next tree over. In

the cropped images, I can see a blister at the front

edge of its mouth.

It looks a lot like fire ant blisters I've gotten. Poor little critter.

I've tried to figure out what kind of toad it is.

After

some searching, I've found that it's

probably a Gulf Coast Toad

(aka Coastal Plains Toad; Incilius nebulifer). I can't see the toad's

body, but those prominent bone crests between the eyes seem to be a

defining feature. I found the information in this: A review of the

biology and literature of the Gulf Coast Toad (Incilius nebulifer),

native to Mexico and the United States

by Mendelson, Kinsey et. al.

(Article in Zootaxa � June 2015 DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3974.4.4)

(update 07/20/2021)-

I returned the next

day--after all, it's where I regularly practice. I was sad

and a bit relieved to see that the

toad

had left. Relieved, because I thought that the toad was at

risk,

even in the hole. Since the toad had gone, I could examine the hole.

From

the top, the hole is about 3cm across (1.2 inches--I'd estimated 1.5

inches). I tried for pictures into the hole. It does have a

visible

bottom. That "ledge" is probably just a hard area in the

substrate that couldn't be burrowed through.

I

was able to see a bit more clearly into the hole than the images show.

So I thought it would be ok to probe a bit with my finger. The mud was

packed, not soft. Also, the narrow

parts are like shelves--that

is, the wall is the same width under it as over it. I

couldn't

tell for sure if the bumps were exposed tree roots. Also, the hole

stops at the bottom, and

does not turn in any direction into

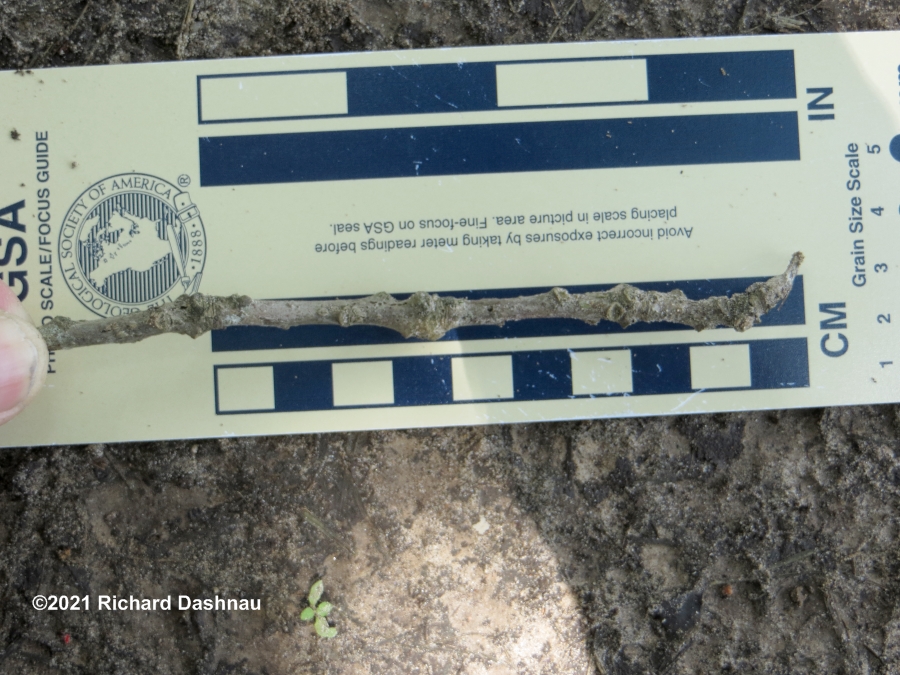

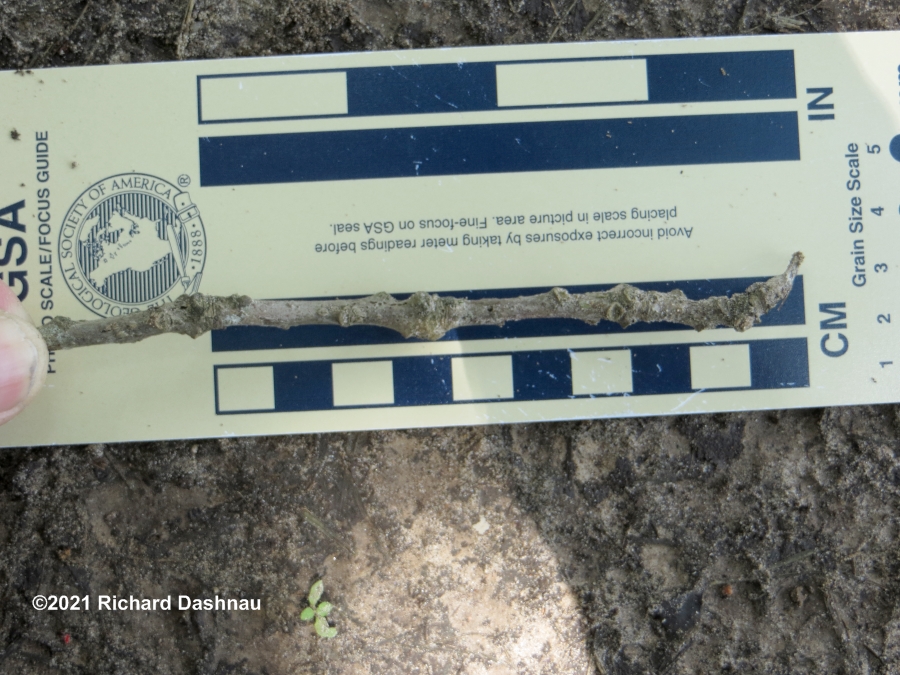

anything horizontal. Finally, I made a "high-tech depth sounding

device" from a twig and placed it into the hole. I pinched it at the

top edge of

the hole, and then-holding by the pinched point-placed

it onto my gauge to get a depth reading. The hole is about 5

inches (13 cm) deep.

05/02/2021 Even

with more "spare time"

it's taking me days to work on new material so I can post it. Part of

the reason is that I get more

new material before I've completed

editing of the previous new material--because I have more of that

"spare time" to go get the new material. Oh, darn. LOL

So, here's how my morning went at Brazos Bend State Park on 05/02/21.

I have more

photos (and some video) but I need to post this now before much more

time passes (it's

already

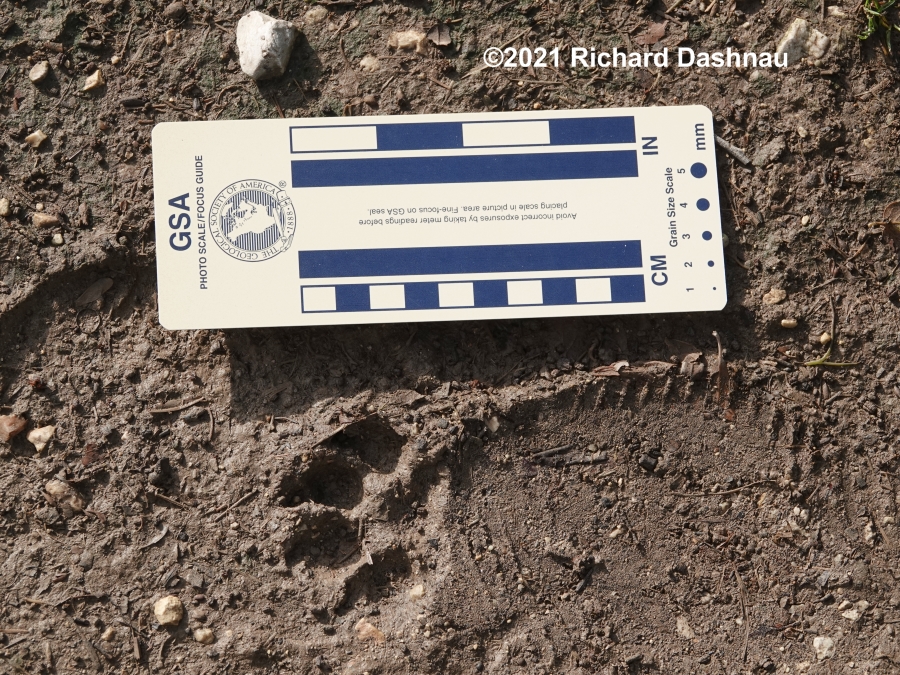

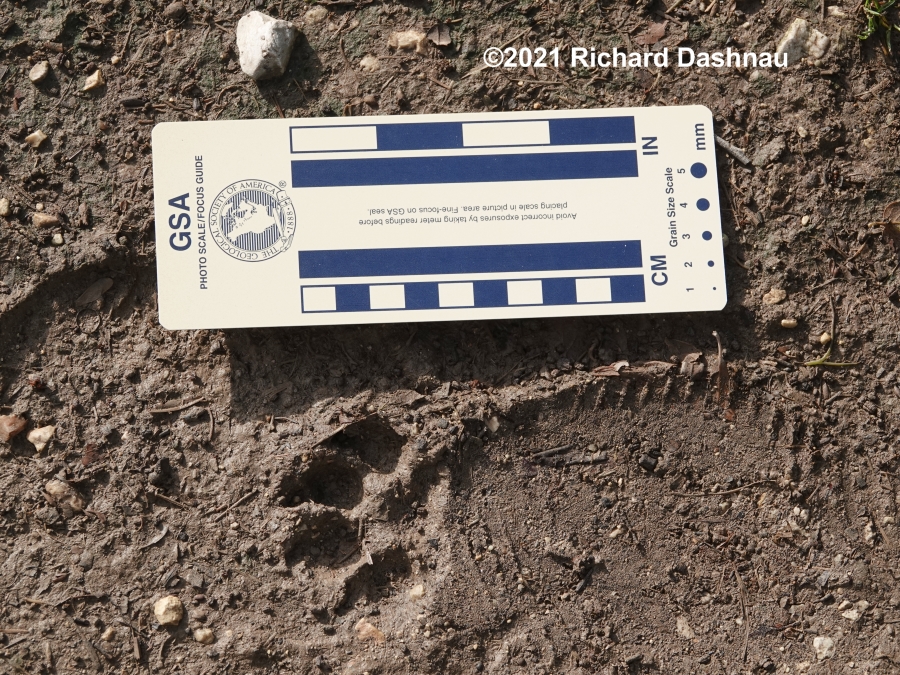

been a week today). I'd just gotten to the edge of 40-Acre

Lake

(had just walked down the hill) when I noticed this set of animal

tracks on the trail. I'm a bit confused

on what made them. I

think they're from a cat because of the short heel pad and outline; but

it look like there are claw impressions and a single "lobe" in front

and two "lobes" in

back--which would make them dog tracks.

Whatever they are, it looks lke they walked on top of the

human

tracks. I'll alter this description pending any expert input.

If

they are

feline

tracks, then they'd probably be from a Bobcat, which would be pretty

cool. (UPDATE)--Alas.

According

to a number of experts, my

second guess was correct. They were

dog

tracks. Thanks to science

twitter folks: Dr. Lisa Buckley (@Lisavipes) ; Dr. Anthony Martin

(@Ichnologist); Zachary Wardle (@ZacharyMWardle).

Animal

tracks!

Go to

Ichnology

page 1.

Go to Ichnology

page 3

Go to Ichnology

page 4 (this has the most recent observations).

Go

back to my home page, Welcome

to

rickubis.com

Go

back to the RICKUBISCAM

page.