ALLIGATOR

BEHAVIOR page 2d: SOCIAL SIGNALS AND BELLOWING 4 1 2 3 5 6 7 8 9 10

This

page was born 07/04/2008. Rickubis designed it. (such as

it

is.) Last update: 11/26/2012:

Images

and contents on this page copyright © 2001 - 2012 Richard M.

Dashnau

Alligators,

although they are ectothermic and also equipped with a small

brain, exhibit

a surprising diversity in their responses to their environment

and to each

other. They are for more

complex than mere animated logs or 12-foot-long

eating machines. This group of pages show some

of what I've been able to

see in the years I've been volunteering (September of 2001

thru March of 2020) at Brazos Bend State

Park.

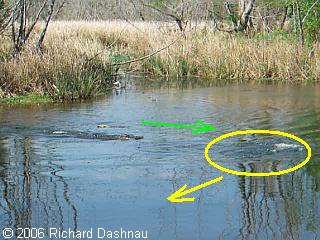

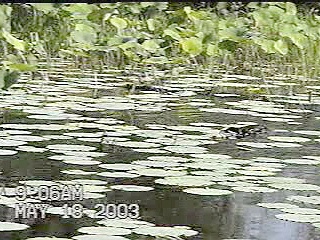

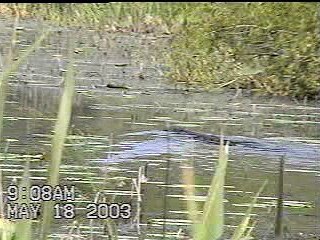

May 18,

2003

This morning, not long after I'd started walking near Elm Lake, I

heard

an alligator head slap near pier 2. As I started hurrying

towards

the sound, I began hearing bellowing. When I got

close to the source of

the bellowing, (it sounded like 2 females and one male) I noticed

a large

male alligator swimming parallel to my course, That is, he was

headed towards

the bellowing. I could just

make out the male that had been bellowing,

when the larger one got close to it. The bellowing male was at

least half

a length shorter than this male that followed me. The smaller

alligator

beat a hasty

retreat to the center of the channel...but only about 25 feet

or so away. The larger alligator showed a puffed-body/tail-arch

posture

for a while, then got closer to the far shore and began bellowing

(see

MY YARD, below or video

clip

(1,452 kb)). When the large male bellowed, I'm sure I felt a

subtle vibration;

similar to what one feels sitting next to a large, low frequency

speaker.

As I looked at my video,

it seemed to me that there is a slight vibration

of the camera near the "waterdance" stage of the bellow cycle.

---- ---

--- ---

--- -

-

MY YARD!

I SAID, MY

YARD!

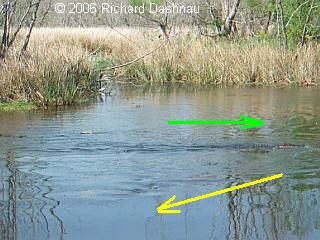

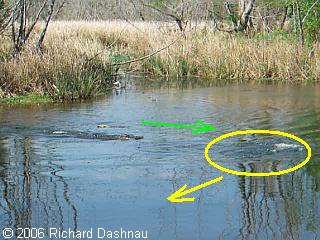

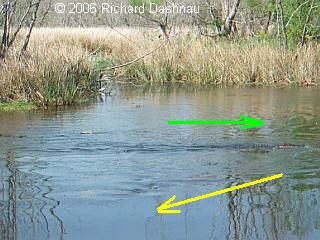

THERE THEY GO

The

large male continued bellowing, and what sounded like two females

(on either

side of the large male) began bellowing as well. This went on for

about

3 bouts. After the bellowing stopped, two

smaller alligators (about 6 or

7 feet long) appeared from the East, swimming alongside each

other.

The large male turned, and swam out to meet them. The smaller one

of the

two stopped swimming

immediately. However, the other one didn't, although

it *did* try to swim around the big male. It was able to move

around the

large one, but the male continued advancing, and then turned to

follow

the

small alligator (see I SAID, above or video

clip (1,424kb)). And then the chase was on! (see THERE THEY

GO, above

or video clip

(678 kb))

This

chase, however, continued down Elm Lake for quite a

distance; maybe 3 or

4 piers. Far enough to require binoculars to see them in the

distance.

That was a nice start to the day.

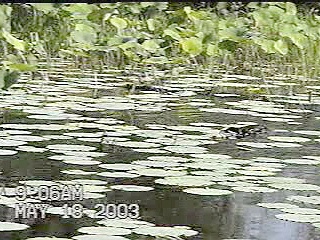

April

01, 2006 Earth Day Celebration at BBSP. I led a "gator hike"

at Elm

Lake. We saw some great alligator behavior, and a territorial

dispute.

Text below added 4/20/2006.

One

of the reasons that I was so excited about seeing this social

interaction

(besides the fact that it happened in front of me) was that I had,

not

10 minutes before, been lecturing to the hikers about

various types of

alligator social signals. Usually, when I lead the hike, I

will stop

near

an alligator and-whether it's doing anything or not-I will lecture

and

demonstrate some aspect of alligator behavior.

Sometimes, while I'm

lecturing

(interpreting), the alligator will do something, and if I haven't

covered

what the alligator is presently doing, I will try to put what

it *is*

doing into some behavioural context.

By the

way, this particular competition was probably driven by

two factors.

First, this is mating season, and alligators are territorial.

Second,

the water in the lakes in the park is VERY low. This means

less area covered

by water, and therefore a lot less available

territory.

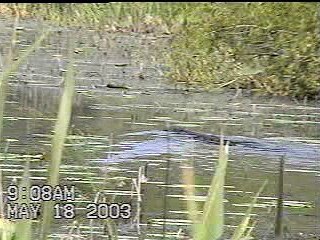

In this

situation, I had just explained how alligators will often indicate

social

status by body position relative to the surface of the water.

The

nose slightly elevated (just the edge of the lips visible)

is

non-aggressive.

Head flat with snout at water surface, is watchful. Submerging

the

head while holding it flat in the presence of another alligator is

submissive.

Back high in the water is dominant.

Head with nose pointing

up sharply

can mean headslap or bellow--both highly dominant signals with the

back

submerged and the tail arched. Tail arched (center of

tail

elevated higher than the

base and tip) can mean readiness to defend or

what I consider a "query" regarding direction an interchange will

take.

These are all positions that the alligator will sometimes take

while feeding,

but then the body positions are in a different context. With

no

other

alligators around these are not signals. All these images are from

the

short video clip I shot. The video clip can be seen here

(mp4)

-

- -

- -

-

AFTER THE FIRST LUNGE

SUBMISSIVE

TRAPPED

AGGRESSOR PASSES

SUB

SUBMISSIVE STOPS

AGGRESSOR IN FRONT

The

headslap is an action where the alligator lifts its head, then

suddenly

drops lower jaw under the surface of the water, then slams upper

jaw

down

to meet the lower jaw; resulting in a loud

pop/slap sound--which is sometimes

accompanied by a short growl as the upper jaw is brought down.

I've seen this often immediately after a direct alligator

challenge. I've

seen either the

apparent winner or "loser" of the exchange (I assume

the

one that submits is the loser) do a headslap. Generally if the

dominant

"winner" does it, the headslap is within view and within chase

distance

of the "loser". Most alligator interaction is non-violent, and

involves

a lot of submission and swimming away.

(examples

of many of these behaviors can be seen on my other pages,

such as the "alligator

social signals" pages:

social

signals

01 social

signals

02 social

signals

03

I learned

a lot of this by watching the alligators use these signals and

others in

context over the last 4 years. An early source for comparision

was

a study available from the American Museum

of Natural history, titled--"Social

Signals of Adult American Alligators", by Leslie Garrick,

Jeffrey

Lang, and Harold Herzog (Bulletin of the American Museum of

Natural History

Vol. 160:

Article 3; pages 157-192, 1978; click here

to see the AMNH digital library and get the pdf.) This is a

very small

publication,

like a small magazine in format, but it is a detailed study

of alligator

communication among animals observed in Florida.

Another

source for descriptions of alligator social signals is:

Crocodilian Biology

and Evolution, Gordon C. Grigg, ed. Feb, 2001.

(pp. 383-408)

There

is also some reference in this book to the earlier work.

-- -

- -

- -

-

AGGRESSOR THRASHES TAIL SLOWLY

TAIL ARCH

WITH

HIGH

BACK

SUBMISSIVE

SUBMERGED

TAIL

ARCH

I'd

talked about what I called the "panic dive". Although alligators

can hold

their breath for a long time (I've read between 1 and 4 hours),

they

cannot

do this every time they submerge. If an

alligator is surprised or

under duress, it performs a "panic dive". In this circumstance,

the

alligator

can only hold its breath for a short time, and generally

resurfaces quickly

to assess the situation

that made it dive in the first place.

I have

often seen this in practice.

In the

book Crocodiles:Inside Out, by K.C. Richardson, G.J. Webb

and S.C.

Manolis, there is a concise description of the circulatory changes

that

happen during what they term a "voluntary"

dive on pages 81-82. According

to the descriptions and the simplified drawings with them,

crocodilians

have two major connections in their circulatory systems which

allow deoxygenated

blood to mix with oxygenated blood.

Remember--mammals

have a 4-chambered heart, which keeps blood rich in oxygen

seperated from

deoxygenated blood, which allows

for

more efficient

oxygen supply to the body and therefore more efficient metabolism.

Most reptiles have a 3 chambered heart, generally

less

efficient because oxgenated and deoxygenated blood can mix

together within

the heart; resulting in overall less oxygen being available to

body tissues.

Alligators, however, have a four-chambered heart! However, there

are to major connections in the

alligator's circulatory system that

allow

for mixing of O2+ (oxygenated) and O2- (deoxygenated) blood.

While

this would seem to lessen efficiency--in fact might seem to be

defects --these

are

part of a complex mechanism which allows crocodilians to remain

under

water for such long periods of time. As time passes while the

crocodilian

is submerged, it can restrict the blood flow to its

lungs (which aren't

used then), skin, and other low-priority organs while

simultaneously increasing

flow

to such high-priority organs as brain and heart; and it also deal

with lactic acid buildup. When

the crocodilian finally does surface

after

such a long period, it breathes normally; without stress incurred

from

its long period without air.

At the

end of this description is a paragraph that states

that during and "involuntary"

or "fright" dive (which I called the "panic" dive")

the

crocodilian can only stay under for a short time. After

this, it

will resurface, breathe normally, and can then perform

a "voluntary" dive

and

remain

submerged for a much longer period of time.

Finally,

I talked about a concept I call "escape in 3 dimensions". This is

a concept

I came up with myself, and I've

been looking for various

examples.

Generally, I consider this a technique that is useful at the

boundary between

two environmental media. Examples are the boundary

between

air and water,

air and ground, or ground and water. In the case of alligators,

I've seen this during social interaction. As I understand

it,

most alligator communication requires water for transmission. A

lot of

information is conveyed by alligator body position relative to

water

surface.

Water is also used for head slapping, bellowing (the

low-frequency

vibration--"water dance" over the back), tail

swishing, and

snout-bubbling

(expelling air from nostrils or mouth to make bubbles).

Alligators

will occassionally interact on land, but such interactions often begin

and/or end in the water.

Alligator

chasing usually happens at the water's surface. The pursued and

pursuer

can move towards or away from each other. In all-out pursuit,

speed

can increase until both alligators seem

like motorboats. Sometimes, a pursued

alligator will raise its tail and thrash it enough to cause

turbulance

and splashing, then turn 90 degrees to the right or left.

Sometimes this

ploy works...

briefly. The turbulance can disrupt the pursuer's

visual

and possible tactile sense (perhaps via ISOs) temporarily while

the pursued

alligator changes direction.

All

of this is what I call "two dimensional" movement. The alligators

are moving

right, left, backwards, forwards--but all in one plane and still

at the

surface of the water. But, if the alligator can't

escape, it may

try in a *third* dimension---down, or up. The alligator may do the

turbulance

trick

and submerge. When it submerges, it may do the 90 degree turn, or

it may

not. But, this is

usually a panic dive, and the alligator usually

can't

stay submerged for long. When it resurfaces, the pursuer can

locate it

and continue the chase.

-

- -

- -

-

SHORT, STRAIGHT CHASE

WHILE SUB DOVE

AND TURNED

AGGRESSOR CONTINUED...

...WHILE SUB SWAM UNDER

If it

submerges, turns sharply, and swims below and at an angle-which

allows

its pursuer to pass it-it may be out of visual range of the

pursuer

when

it resurfaces. The alligator may also go

"up" by leaving the water and

walking onto land. This ploy may work not because it becomes

invisible

to

the

pursuing alligator, but because alligators are less comfortable on

land

and the

pursuer may not want to follow. The story I have on another

page

about the alligator with a mouthful of nutria being chased by

another alligator

trying to steal it (and eventually others trying to

take it) illustrates

some

of these movements. That alligator chase also shows a number of

social

signals, my "escape in three dimensions--both onto land and under

water",

and

panic dives. You can see it on this

page.

Before

I shot this video, this aggressor ("dominant") had been

cruising

the water nearly an equal distance from both banks. My hiking

group and

I

followed

the patrolling alligator past 3 or 4

piers. One smaller alligator

moved ahead of it, and eventually cruised to the far bank and kept

a low

profile.

One alligator already at the bank slowly submerged as the

aggressor passed

by.

Finally,

the aggressor moved towards a 7-foot alligator that was resting

with the

front half of its body out of the water. The dominant

slowed,

and

inched towards the beached alligator until

it must have been floating over

the tail. Suddenly, there was a flurry of motion as the

beached

alligator

(which might have suddenly come awake) seemed to realize that the

aggressor

was

so close and lunged onto the bank. The aggressor

moved

towards it again, and that's where the clip starts. If you watch

the video

clip from 04/01/06, you'll see the aggressor's side-to-side

tail

swish, indicating annoyance. The aggressor has his back high in

the water,

then turns back towards the alligator which had run onto the

bank attempting

to

escape (it also didn't have

much choice, since the aggressor was already

on top of it when it was noticed). There's a sharp jump-turn

into the water, and a panic dive. The submissive ("sub") surfaced

off to

my right

(you an only see tail turbulance), which signalled its location

to the aggressor, which chased it. The sub turned 90 degrees

again

(to my left), and did a shallow dive. Its escape route brought

it right

to the

bank in front of us. With a crowd of 20+ humans on the trail

above, I didn't

think it would retreat onto land, but I warned everyone to

stand

back anyway.

Here

the submissive remained, waiting for the aggressor's next move.

When the

aggressor lunged forward again, the submissive did another panic

dive,

and went off to my right, bringing it

behind the aggressor, and some distance

away. *I* was confused, since I had been watching the

aggressor's

position relative to my group of visitors and was assessing this

situation

instead of just watching the alligators.

-

- -

- -

-

SUB TRAPPED AGAIN

SUBMISSIVE ESCAPES...

...GOING

UP, AND THEN...

...GOING

UNDER AND TURNING

SUB ANGLES BEHIND

Meanwhile,

the aggressor--who had lost his quarry but didn't know it

yet--stood

with it's arched tail switching side-to-side, its back very high,

and

its mouth gaping open. I've seen the alligator gape as a

threat display--but

open mouth by itself isn't necessarily a threat. It depends on

the

context. An alligator sunning on a bank for a long time will

sometimes

open its mouth as a heat-regulation reflex. There's no tail

thrashing,

body

movement,

etc. In this case the gape was obviously meant to

intimidate.

It worked on us, that's for sure!

-

- -

-

SUB

SWIMS OFF WHILE...

...CONFUSED BY TURBULANCE...

...AGGRESSOR SURFACES...

...WITH MOUTH AGAPE...

...BACK HIGH AND TAIL THRASHING

When

the water stopped moving around, the aggressor could see another

alligator

in front of it. It went towards it, but that one wasn't

the

alligator that had made the aggressor so angry,

and after a brief close

inspection, it left it alone (this is also interesting since it

showed

that the aggressor wasn't attacking every other alligator,

and could

therefore tell them apart.)

Finally, after having driven

off

the other alligator, the aggessor moved a little further off (to

the next

pier), and did a head slap. This was reported to me later by a

number of people who

witnessed it.

This

"escape in three dimensions" or "escape across a media boundary"

is an

exciting concept for me. I've seen some birds do something

similar.

A Coot

and a

Moorhen might get into an argument and start swimming after each

other (left, right, forward, backward--one plane--2 dimensions).

At a

certain point, the target may start "fly-running"

over the surface of the

water, or just take off, or submerge (movement up or down, escape in another

plane--3 dimensions). A squirrel will run here and there

(one plane)

if there is no

tree, but once a tree appears, UP it goes. Rabbits

may go down,

if there

is a burrow. One example that got me onto this line of

thinking was

the basilisk lizard. It can run well on land,

but if pursued near

a body

of water, it can run across the surface for a while, before

submerging

and swimming away. What the lizard is actually doing is striking

the

water

with

outsplayed fringed toes hard enough to make a big "hole" in the

water;

and the then pulling its foot up out of the hole faster than the

hole

can

close. This is made easier by the toes

closing together which makes the

foot much smaller as it's pulled up. While that foot is pulling

up, the other

is

pushing down, and so on. A simple description of this can be found

in

the

book, Extreme Science: Chasing the Ghost Bat--from the editors of

Scientific

American, pages 82-83. Or, you can look for the

papers--"Size-Dependence

of Water-Running Ability in

Basilisk Lizards" by J.W. Glasheen

and

T.A. McMahon and/or "Running on water: Three-dimensional force

generation

by basilisk lizards" by S. Tonia Hsieh and George V. Lauder--for

the

technical data. There are a lot of complicated mechanical

relationships

at play here. Not only is the lizard using the surface of

the water

to run

on;

but it's also keeping its balance

and moving forward rapidly!

Anyway,

this "three dimensional trans-medial movement" needn't just be

used for

escape. Some predators can attack successfully between media

boundaries,

surprising prey with

an attack from an unexpected direction. A mouse can

run in any direction horizontally, or burrow down...but it can

still

be surprised by an owl or hawk attacking from another medium

(air) and

third dimension (up).

An osprey

can cross the boundary between air and water and snatch food out

from one

medium (water) and bring it into another (air) with the fish

being

totally surprised. The ant lion pulls prey through the

boundary of

the ground from below. The prey is caught unawares by this attack

from

a third direction.

The

trapdoor spider also uses

this third dimension to suprise prey expecting

attack from everywhere but the medium it is walking on. And, of

course,

crocodilians can use this concept as well, and snatch prey

through the

boundary of air and water, or water and land.

©

2006 Richard Dashnau

And, this page

shows alligators at the park, on land, near various landmarks at the park.

Go back to my main alligator

page, Alligators

Go

back to my home page, Welcome

to rickubis.com

Go

back

to the See the

World

page.

---

--- ---

--- -

-