CRITTERS

AT BBSP AND ELSEWHERE page 6 Insects: non-toxic

This

page was born 10/31/2005. Rickubis designed it.

(such as it

is.) Last update: 06/30/2023

Images

and contents on this page copyright © 2002-2023 Richard M. Dashnau

Go back to my

home page, Welcome

to rickubis.com

Go

back to the RICKUBISCAM

page.

----------------------------------

Welcome

to the Visitor's Center at Brazos Bend State Park. That's me

with the

giant

walking stick (06/20/2004). As I get more material in my domain,

I'm

able

to give a separate

page to various animals. This page features non-toxic

insects. I feel that toxic insects each should have their own

page for

easier reference.

05/28/2023 Brazos Bend

State

Park A week ago 5/18, I had noticed that the den I call the "40

Acre

West Den" by the Buttonbush (Cephalantus

occidentalis)

showed

new signs of use (grass flattened, slide mark in mud). Since

then, I've been stopping by to see if I could find an

alligator

in or near it. There appears

to be a grassy hump

in front of the den, but I don't think it's a nest. After

comparing

with older images, I can see that the hump has always been there.

Grass

grew on it, and

now that it's flattened it gives the illusion of a

pile of grass stalks. I believe that it's just a layer of crushed

grass

on top of the mud hump and not a pile of old grass. The 4

images below show the den earlier this year.

01/01/2023

01/22/2023

02/12/2023

03/19/2023

While looking at the bush today, I

noticed the amazing flowers on the Buttonbush (Cephalantus

occidentalis), and decided to take a few pictures of those.

While

I was shooting photos, some butterflies and a few wasps came by. I

think that this was a Black Swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes), and

it's a

male--at least judging

from the colors when I compared with images online. I

thought

my photos were nice, so here they are.

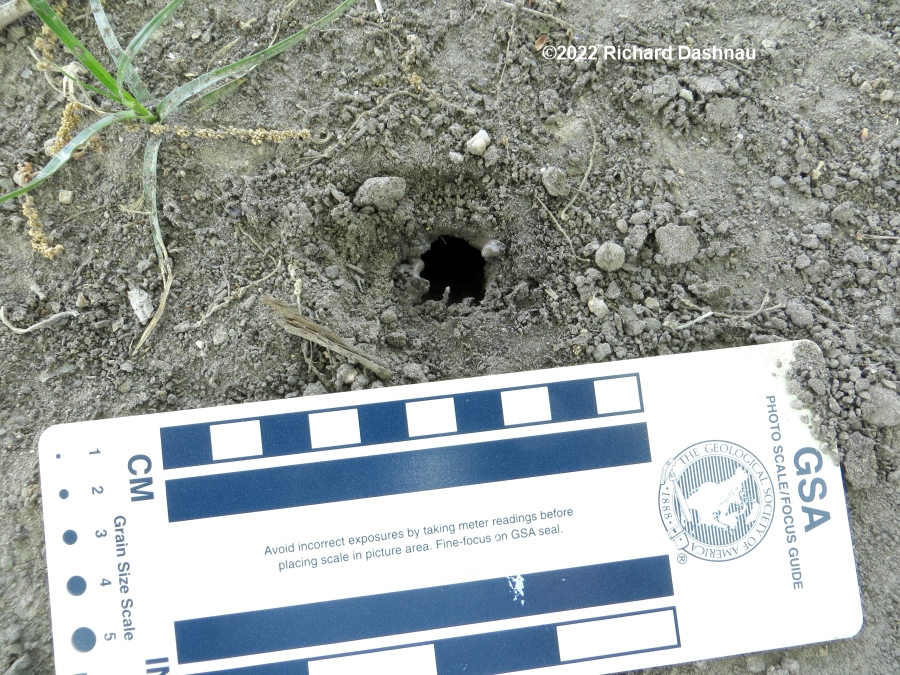

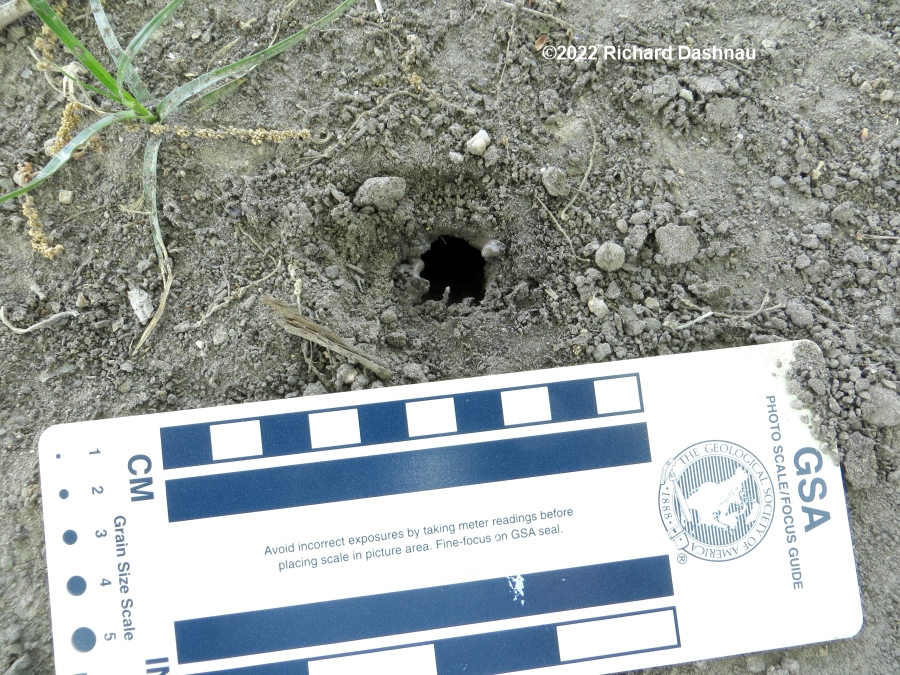

In Houston on 05/11/2022

At my exercise area, I noticed another mud "cast" on the dirt

trail.

This time, I thought I knew what it was (because of what I'd

seen a week

ago), so I got the camera before investigating. I pulled

up

on the "plug" and uncovered another cicada nymph burrow. Click

the

link for a short film that includes some of these photos

as well as some video clips.

About 5 minutes later, a

cicada nymph showed its face, and started

applying

a paste to the edges of its hole. As with the previous nymph,

this one

withdrew, then returned a few minutes later to add more paste

to the

edge of the hole. I replaced the plug

and left something near it so I wouldn't step on it, and

started my exercises.

This

is the second time I've seen a cicada nymph produce

"paste".

I figure

that it's partially-composed of dirt; but what is the

moistening agent?

The ground was dry, and I don't think there

was "mud" just a few inches

down. Do the nymphs secrete liquid? If they do, what is

it--water,

mucus...something else? How much can a nymph produce?

About

20

minutes later a Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus)

landed

nearby (as they often do while I'm working out), and began

foraging. I

happened to be looking at it when it

noticed the "cicada plug" and

moved towards it. My camera was on the ground near the plug. I

moved to

the camera as the Grackle moved towards the plug and started

to pry it

up. I hoped

to capture this on film but the grackle stopped digging

moved away when I picked up the camera . So the most I could

do was

take pictures of the excavated plug. I moved around the

tree

to let

the Grackle continue, when it found another cicada hole and

started

digging at it. I got a few pictures some video, but the

grackle gave up

and walked off. This

is another

example

of Grackles recognizing

and exploiting a food source. They (or at least one of them)

recognized

a small pile of dried mud as a place to dig for food!

Exploration of an

open hole is also

noteworthy--although I think many animals explore

voids or openings in the environment. For the Grackle to

recognize that

the pile of

mud was different and worth investigating seems

pretty

cool.

From Houston on 05/02/2022.

I was checking my exercise area for stones and poop when I

noticed this

lump. I didn't want to step on it for many reasons. I could

already

tell that it wasn't poop, but thought it was a burrow casting

of some

kind. When I picked up the lump, what I uncovered was so

interesting that I put lump back, then delayed my

exercise to

run back to the car and get a camera. Then I lifted the mud

lump again.

The hole looked like a cicada burrow (I often see them

here).

But

the fabricated mud cap had

confused me...

...until the owner of the

burrow appeared.

It

was a cicada nymph! Then it returned to the depths. By

the

way,

the images of the nymph below are from video I filmed

then.

You can see the

short video

here (mp4).

I

waited a while, and it made another trip. I've seen many

cicada

burrows-here, and at other places. But this behavior was new

to

me, so

I did research after I got back home. Cicada

nymphs sometimes make a

chimney, turret or a cap over their burrow while waiting to

emerge! I

saw pictures online of some turrets that resembled small

versions of

crawfish chimneys.

Type

"cicada chimneys" or "cicada turrets" into your favorite image

search

and you'll see what I mean. This really surprised me.

I'd

just

assumed that the nymphs came out of the ground

when they are ready

to do their final molt, climbed up, and did their final "pop".

But

apparently sometimes they "wake up early", hit a snooze button

and go

back underground for a while.

I was also reminded by many

references to how Copperheads like to hunt for emerging

cicadas--and

possible increase in numbers of Copperheads during Cicada

emergent

times.

This

is the underside of the cap that I removed. It was hollow on

the

bottom. I put the cap back over the hole. Note how dry

the

dirt

is--the cap had not been"glued" to the loose dirt .

I put my tripod over the hole so I wouldn't disturb it

further when I resumed my exercises.

06/17/2021

As

I was walking my dog this morning, I found this cicada nymph on

the

sidewalk. Since I was nearly back home, I carried it back with

me-to

save it from getting stepped on, or

eaten by a dog, etc. I put

it on the trunk of an Oak Tree, and it climbed away. The first

time I'd

ever found a Cicada nymph (during childhood), I was very

impressed by the sharp and

formidable-looking hooked forelegs.

Back then, I assumed that what I'd found was some kind of

predator.

Many years later, I learned what I'd found, and that the

raptorial

("raptorial"

= "grasping") forelegs were mostly used for climbing. The hooks

and

points are very sharp, though,and clung easily to my skin. They

also

work well on bark. The images showing

my hand below are frames from a video I shot.

10/06/2019 Green

Darner

Dragonflies (Anax junius) are large, beautiful dragonflies.

The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Insects

and

Spiders says they're: "2 1/4 in.

to 4 3/4 in. long with wing span up to 5 7/8 in. (p. 364)"

A

recent study: Tracking

dragons: stable isotopes reveal the annual cycle of a

long-distance

migratory insect

(Michael T Hallworth , Kent P McFarland Dec. 2018) indicates

that Green Darners migrate hundreds of miles--from the North of

North

America, to the South, then back. But...in

succeeding generations. First

generation is born in the South migrates North during the

spring

lays eggs, and dies. At the end of that Summer, some

newly-mature

adults migrate

South--though some remain as nymphs until the following spring,

when they mature and

fly

South. The 3rd generation stays in the South through that

Summer and Winter. Next Spring, that

generation matures and

starts the 3 generation cycle again. (If you can't get the

Hallworth/McFarland study, this has been summarized in a number

of

places like this one.:

https://www.sciencenews.org/article/green-darner-dragonflies-migrate-bit-monarch-butterflies

This

week, I noticed a great number of Green Darners at BBSP--maybe

the

third generation getting their last mating in before winter.

With

all of that going on, some of the Green Darners

don't make it. Some

wind up in the webs of Golden Silk Spiders (Nephila

clavipes)--like

the one below. Notice that just to the right of

the

dragonfly, there's a tiny Argyrodes spider hiding

out. This short

video

clip shows the Nephila tying her meal to her

web. I do have other images of the small Argyrodes on my web

page here.

08/13/2019

As I was finishing some

exercises at Memorial Park, I noticed something moving in the

grass

towards my

exercise circle. Since the path was covered with

fine-grained

dirt, I saw

an interesting opportunity.

I retrieved my camera and took some pictures and some

video.

Then, I was able to do an exercise in ichnology.

Ichnology is

the study of animal traces. It is

commonly used in relation to

paleontology; so sometimes "neoichnology" is used to refer to

traces

left by living (extant) animals, and "paleoichnology" for fossil

traces. Three elements can

produce a trace: substrate (the

recording medium i.e. mud, sand, etc.), anatomy

(physiological

structures), and behavior (what the animal did while leaving the

trace). I don't have a good

eye for identifying a trace, but in

*this* instance I could watch it happen. So, the 4 images

below show

the tracks-of course, after the animal crossed. From left

to

right, I enlarge the view.

My camera tripod shows scale.

Its an oddly-assymetrical trail.

The four images below are from the

video

clip, and they show the track maker as it made the

tracks.

The

culprit was a larval cicada! It had come out of the ground

and

was looking for something to climb upon so that it could

complete its

tranformation into an adult.

June 29

and July 6, 2014 Robber

Flies (especially the large ones) can make an impression just by

flying

by. Sometimes, they are carrying something they just caught. And

sometimes they

just

fall nearby with something they've just ambushed in mid-air.

Here

are a few images that I took on these two days. Note that I uploaded

(published) them in 2016, although I took the

pictures below in 2014. First is one that was patrolling from that

stalk. The

next image was at the Nature Center, and I had seen the Robber

Fly land on the building. It has caught a wasp.

The

third image shows a fly that fell to the trail in front of me,

with a

dragonfly it had caught. The fourth image shows a fly on the

rail

around the air conditioner at the Nature Center, and it

seem to have something,

but I can't tell what it is.

-

- -

- -

- --

--

February

01, 2013 Today

I

visited the wonderful Houston Museum of Natural Science again,

something I've been doing a lot more since the new Paleo Hall

opened.

However, today I visited

the Cockrell Butterfly center, and

the Brown Hall of Entomology. I went through the

Hall first,

thinking that I might need to pick up some information before

entering

the rainforest of the Butterfly

Center. The hall of Entomology also

discusses some of the other arthropods besides insects. There was

a

large spider that must have gotten loose. I looked around, but

just

couldn't seem to

find it.... (see the RICKUBISCAM image below)

--------------------

After

escaping, I continued through the Hall, where I saw the butterfly

"chrysalis corner". I observed people inside the cages,

gathering

butterflies. I didn't realize the importance of of this until

just a

few minutes later. I finally entered the rainforest, where

water

fell from the a rock face to a pool about 1 story below. In about

a

minute, I noticed all the butterflies flying around. And...

...I

got to see the release of newly-changed butterflies! Some

were

ready to fly--but others hadn't had their wings fully-hardened

yet.

These were gently placed on trees, to hang there like

Christmas

ornaments.

___

___

HANGING

LIKE

ORNAMENTS

Rice

Paper Butterfly (Idea leuconoe)

As

I looked at the butterflies hanging there, and while I was

chatting

with one of the entomologists, I suddenly remembered a picture I

had

seen just a week ago. It was a butterfly that had

coloration on

its wingtip that resembled the head of a snake. Just then, I was

looking at the very same species of butterfly--about 2 feet in

front of

me! I could have touched it (but I didn't,

because that can

damage the wings by rubbing the surface off) but I did take some

pictures with my pocket camera. From what I can see from the

identification sheets that the museum

loans out, it is a Tawny Owl

Butterfly (Caligo memnon). Now, I'll admit that

when I saw

the article and and picture on the internet, I was a bit

skeptical.

After all, of what good would it be for

the edge of the wing of a

butterfly to resemble a snake's head? How would that work as

camouflage--especially considering that the butterfly also has two

LARGE spots and colors on the

wings that closely resemble the wide eyes

of an owl.

___

___

Tawny

Owl

Butterfly (Caligo memnon)

SNAKE'S

FACE!! NO, IT ISN'T

SNAKE WITH

HEAD UNDER 1 COIL

I

think I may have stumbled onto just the right time and place to

show

how the snake's head might work. The butterflies wings were still

not

fully-expanded (but almost). AND... the butterfly was

hanging

upside-down. Seen in this way (and maybe the light was just

at the

right angle--I don't know), the *entire* butterfly in

profile

looks like a coiled snake, with the head underneath the

coils. At least

it does to me. Since the butterfly can't

fly yet, maybe appearing as a coiled snake would scare predators

away.

This can only be verified by expermentation with whatever

would

normally attack this butterfly in it's home ecosystem.

I followed the trail and enjoyed the rainforest for a

while longer, and then continued to the Energy and Paleo halls.

10/19/2009--Green

Darners

(Anax junius) are one of the largest dragonflies.

Sometimes, if I catch it right, I can watch one stationary

in

the

air as it flies against a wind. The image below

is

a framegrab from a high-framerate video that I shot of a Green

Darner

caught this way. The video

clip

is here.

-

-

4/30/2006--This

is the last story from this single day, and last for for April as I

continue

my update bonanza.

While

inspecting the deck near the VC/NC, I found this caterpillar

resting

along

one of the crosspieces. Caterpillars are hard to identify, but a

cursory

inspection gives me the impression that

it resembles the larva of a moth.

This moth is called the Gloomy Underwing, or Andromeda Underwing (catocala

andromedae). Underwing moths are called so because the pair

of rear

wings is usually a contrasting color from the pair of front wings.

These

are held under the front wings (which are usually a color

well-suited

for

camouflage). The moth can suddenly show these

highly-contrasted underwings,

which causes a startling color effect.

Searching

the internet yielded the information that this particular larva

seems

to

have a diet consisting of a number of

plants. For one website out of my

domain that describes this moth, click here.

For

more information on caterpillars in general--also outside my

domain--click

here.

Why

did this catch my attention? Look how BIG this caterpillar is!

-

- -

- -

- ----

----

AT

REST

HEAD

END

CLOSER

EVEN

CLOSER

PAIRS OF EYES AND TWO DARK SPOTS

--

--

WITH A

QUARTER

THE QUARTER, CLOSER

June

20, 2004. Volunteer

Chuck Duplant found this

GIANT walkingstick on one of our trails. When I walked into the

Visitor's

Center and saw it, I just couldn't believe what I was seeing!

It's

kind

of surreal to see a live insect as large as this right in front of

you.

According to some websites, the giant walkingstick (Megaphasma

dentricus)

is the longest insect in the U.S. The

image below (QUARTERSTICK) shows

the giant walkingstick with a quarter (and my hand) for scale.

WOW!

They

are relatively harmless, though, unless you are an oak leaf.

That

is, they

are herbivores, and are not known to use any offensive chemical

defences (not like the two-striped

walkingstick, Anisomorpha bupestroides) . Below are

a few more

pictures of this

humongous insect. First (RICK STICKING AROUND) shows me

(I'd been working outside) holding the giant walkingstick. The

next

(RICK'S

NEW FRIEND, CLOSER) is a cropped closeup

of the same image. The third (LET'S

SHAKE HANDS) is a face-on view as it is walking up my arm. The

fourth

(BIG

AS MY HAND) is a frame from a short

video

clip showing it crawling on

my hand. It *is* as big as

it looks, and it's alive!.

-

- -

- -

- -

-

A QUARTER STICK

RICK STICKING AROUND

RICK'S NEW FRIEND, CLOSER

LET'S SHAKE HANDS

WALKING ON MY HAND!

WALKING

ON

MY HAND VIDEO 584KB

August

24, 2003On

a different note, I have to relate an incident that happened at

the

VC/NC

today. We've been gifted with the nocturnal appearance of a type

of

click

beetle that has two

spots that glow in the dark like eyes. Evidently, the

appearance of this beetle was exciting news for some local

entomologists.

They (the beetles, not the entomologists) are quite

striking,

and the glow

from the spots is easily visible in a lighted room with just a

small

amount

of shading. One of the park people had taken a beetle out to

show

everyone, and we were all being

impressed. I turned my back for a second,

and when I looked again, everyone was looking up.

"Where'd

it go?"

"It

went up towards the light!"

"There

it is; it---OOP! Spider got it!"

There

were a few moments of silence....

Most

beetles can fly. This species of click beetle can fly. It flew

from the

palm of the hand holding it to land on the upper edge of one of

the

fluorescent

lights---where, we (and the click beetle)

discovered, a spider lived. When

it landed, a spider immediately ran out, grabbed it, and

disappeared

back

above the light. End of beetle. Fortunately, there

are many,

many more.

August

4/August 5 2002This

story

actually

started right after my encounter with the arboreal Dolomedes

Albineus.

The Live Oak trees near the Visitor's Center have had large mats

of

silk

on the bark for some time. In spots, this silk is quite thick, and

many

visitors, and some volunteers (including me) also wondered what

caused

it. See (SILK 1, 2, 3, below)

- -

- -

-

SILK

1

SILK

2

SILK

3

Close

examination didn't show anything obvious (like spiders or

caterpillars).

I'd wondered if the silk had anything to do with the Dolomedes,

but the

link was just circumstantial (both

happened to be in the same tree).

Finally David (park naturalist) had an answer (well, I guess no

one had

asked him before.). The creatures responsible were called

"barklice".

These

are

not true lice, but actually insects. Well, of course, I had to

find

more information. I looked on the internet, and found some

information,

but not many pictures. So, I decided to go back to the

park Monday (August

6. I'm taking time off from work anyway. HAHAHA!) and try to see

some

of

these insects. I was successful! Some of these images show a

closeups

of

one on a page

from a small notepad. One (UNDER THE SILK, below) shows them

on the tree, after I've pulled some of the silk away. These

insects are

extremely small, and difficult for me to photograph.

I'll return and see

if I can get some better pictures. in the meantime, these will

have to

do.

-- -

- -

- -

-

UNDER THE SILK

AT

KNIFEPOINT

THE KNIFE POINT

ON THE KNIFE BLADE

Ok.

So, these are barklice. But what are they? What do they do?

Well,

they are insects, in the order Psocoptera. They are very

small. They

live in large groups. They eat molds, fungi, pollen,

dead insects,

aphids, and other similar material. In short, they "clean the

tree's

bark".

The barklice build the silk mat to work under (click on these

links to

see video clips of barklice

part

1 (flv video 1,214kb), or, part

2

(flv video 618 kb)). After they're done (probably after

they've exhausted

a particular area of all small foodstuffs), they leave. According

to

some

accounts

I've read, they remove the webs. After finally seeing how small

these insects are, I'm amazed at the amount of silk that they can

produce.

This has to cost the insect some survival resources.

If they produce this

webbing by processing what they eat, then how much debris must

they

consume

just to produce a single silken strand? How much to cover the

large

areas

with those mats

of silk? These are not to be confused with the various

caterpillars that may build tents in the leaves of trees. Barklice

seem

beneficial for the tree, and seeing these webs (which are close to

the

bark, and not in a "tent" or "globe" configuration) should

probably be

a good omen for the tree. I, for one, am happy that

this "mystery"

is finally solved.

If

you'd like to know more about the park follow these links:

Brazos

Bend State Park

The main

page.

Brazos

Bend State Park Volunteer's Page

The

volunteer's main page.

Go

back to my home page, Welcome

to rickubis.com

Go

back to the RICKUBISCAM

page.

Go

back to the See

the World

page.

-

- -

- -

- --

--

-

- -

-