This page was born 01/27/2010. Rickubis designed it. (such as it is.) Last update: 2/15/2025

Images and contents on this page copyright ©2002-2023 Richard M. Dashnau

Go back to my home page, Welcome to rickubis.com

Go back to the RICKUBISCAM page.

----------------------------------

That's me on a trail at Brazos Bend State Park (BBSP), sometime in 2004. This page will collect images and videos of various birds that I haven't collected onto their own pages.

At Brazos Bend State Park 10/29/2023 I was at the East end of the Spillway Bridge. Another volunteer was talking with some visitors who had come

up looking for bird called an "ani". Since I was unfamiliar with the name, I listened while they talked about the bird. One of those folks found one in a tree about 50 yards

away. At first glance, the Ani resembled a Grackle. The Ani was about the same size as a Grackle, black, and had long tail feathers. If the others hadn't pointed it out,

I would have never noticed the Ani--since Boat-tailed Grackles and Great-tailed Grackles are fairly common in the park.

But, on closer view, the Ani's face is a LOT different--it has a big tall, humped beak. This ani's beak had grooves along the side-so it's a Groove-billed Ani

(Crotophaga sulcirostris). I noticed rough feathers on the front of the throat; and there is a delicate tracery of light markings on the head, down the back, and

around the upper chest. The rest of the body covering is mostly black, but I also didn't see that iridescent blue highlight that Grackles' feathers show in bright light.

While I watched the Ani through the camera, another one landed next to it. After shooting some pictures and video I went to check on the mother gator and pod which

was only about 20 yards further down. As I have over the previous month, I mostly stayed near the pod. While I was there, the pair of Anis moved through the trees

in front of me, and then hunted a bit in the cover. So I shot some more pictures and video of them. I lost sight of them when they moved further into cover.The

video of their visit can be seen here.

The Anis called a few times, but because of the wind it's not captured on my video. The call is nothing like the harsh sounds made by Grackles. So, I went back to the

pod. But I continued thinking about the Anis, and read a bit about them. While I had the impression that their appearance in BBSP was rare, many sources I read count

southern Texas as part of the normal range of Anis. Most of their range is Central America and Northern South America.

I found that Anis are in the same family as Cuckoos and Roadrunners--family Cuculidae. Their feet are zygodactylous; which means their toes are turned so they form

2 pairs (2 toes front, 2 toes back) which is helpful for perching and climbing. This is why we can see only two toes grasping the branch in front of the bird. Woodpeckers,

parrots and owls also have such an arrangement. Anis mostly eat insects, but will also eat other small prey-such as lizards; and sometimes eat small fruit.

I keep thinking about how I'd have easily mistaken the Ani for a Grackle, since on some days, Grackles are part of the usual scenery. And, that today is Halloween, when

things are sometimes not what they seem. I have further noticed that the huge beak and lightly-traced markings on the head and chest of an Ani could be an effect

duplicated by a bird-sized full-head mask...a mask that could be placed over the head of an "ordinary" Grackle! What's more likely? That an Ani has turned up in

BBSP some miles out of its normal range--or that a couple Grackles have decided to dress up for Halloween? Ha ha ha! I'm joking. Of course it's the second choice.

The Crows are probably in on the masquerade.

On 03/19/2023 A cold front had passed through recently. That morning, the thermometer in my car showed 47°F. I didn't bother trying to record the air temperature on the

trail because I was trying a new piece of equipment that I thought would give me related data. I can say that it felt REALLY cold out there. Various species of Swallows were

foraging at the various lakes in the park. The first ones I saw were at 40 Acre Lake, and then I encountered more of them near the Southwest corner of Elm Lake, near the

spot where the Limpkin was hunting (that will be below this bit). These images are all frame grabs from the video clips which I edited together into

this film (filmed at high framerate, slowed 8x). Most of the birds I saw seemed to be Barn Swallows and Tree Swallows. A mixed flock of these Swallows flying together as

they hunt is a wonderful sight, and many park visitors commented about them that morning.

Barn Swallows 40Acre Lake Barn Swallow Elm Lake Barn Swallow Elm Lake Tree Swallow Elm Lake

Tree Swallow Elm Lake

03/06/2021(sunrise) I was taking my dog Piper for our 2-mile walk at sunrise. I was surprised when a herd of Peafowl (Peacocks(males) and Peahens(females)) appeared on one of the side streets.

(I'm going with "herd" instead of "flock" because they weren't flying. If that's not correct...oh, well.) And, actually, a group of Peacocks (Peafowl) is known as an "ostentation". That would be appropriate as this

group strutted out. I held Piper back, and stopped to watch the procession. I thought that they'd just pass by. They did not. They walked towards us!

They're watching us. They passed by like a parade! Then they watched Piper and I like we were the parade. Piper was amazed.

NOW what should I do? I figured that a group of birds would approach a human and a dog either to challenge them (maybe a fiesty dominent male); or because they thought I had food.

I watched for signs of aggression, and when I didn't see any, I spoke softly to the birds (after a quiet command to Piper to stay)--so they'd recognize me as a human. I didn't want to

upset them for many reasons. I didn't want to trigger any agression...but I also didn't want them to run into the main road behind me. The group (I'm not going to type "ostentation"

repeatedly. Maybe I'll go with "muster"). finally did start poking around the plants, so I continued past them. When I got to the next curb I stopped to watch them again--and they

started following me. This would have been unfortunate. I had no idea where the birds belonged, so I couldn't walk them home. I didn't want them to follow me down the main road, either.

I spoke to them again, and told them I didn't have any "peacock food" (HA HA HA). Then I stood still again. The birds finally lost interest, and wandered back towards their street.

I think there were two kinds of Peafowl here. I think there were Blue ("Indian" (Pavo cristatus)) and Green ("Java"(Pavo muticus)) with me this morning. By searching the internet, I

found that both species of Peafowl are in the same family as Pheasants (Phasianadae). When at home in their usual habitat, both species are generalist omnivores, and will eat fruits, seeds, insects,

small reptiles, plants--or apparently anything that they can find or catch. I also read that those that have been made pets (as my visitors must have been) will eat various varieties

of pet food. n I continued my walk with Piper. It was an interesting change to our usually quiet walk. I took a few photos and short video clips--holding the phone while walking a dog

is unnecessary distraction. The video(mp4) is at this link.

Oh, great. Now they're following us. I just wanted them off the road. Piper and the birds eyeballing each other. The Peafowl finally understood I had no food.

01/16/2021 - 01/17/2021 While I was at Fiorenza Park North on January 16, I noticed some photographers. They were interested in a flock of Cedar Waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum)

that were eating berries. I think the plants are Privets (Ligustrum), either Chinese (L. sinense) or Glossy (L. lucidum). I am not familiar with many bird species, but I can recognize a few.

I've always recognized Cedar Waxwings by the overall color, their crest, their black eye mask, and their bright yellow tail tips. This day, I wondered why they were called *waxwings*

(feel free to laugh at this part of my story). The Waxwings would leave the berries, then go back after about 15 minutes. An American Robin (Turdus migratorius) kept chasing the Waxwings

off the berries. It eventuqlly left, allowing the Waxwings to eat in peace. The 4 images below were taken on January 16, 2021.

Up at the tree tops. Recognizable as Waxwings Crests on heads, masks, yellow tails. Grumpy Robin wouldn't share breakfast.

After a little research, I saw that a feature unique to this bird are red tips on some their secondary flight feathers that look like dabs of red wax. It is actually a clear coating

over red pigment. Once I learned that, and saw it in some of my images, I wondered what such an odd color or device might be for. After all, other birds apparently don't have them.

The remaining pictures below were taken on January 17, 2021. I also filmed some video clips on the same day, and edited them together into this 4 minute short (mp4). The video

was filmed at different rates. It's a nice way to watch Cedar Waxwings for a few minutes. Don't laugh too long about my lack of knowledge about the "waxwing" description.

I looked into the "Cedar", and if I understand correctly, "Juniper Waxwing" is a more precise name. That is, if Cedar Waxwings were named because they like to eat Cedar Berries.

My research indicates that "Cedar" trees that produce these berries are actually Junipers.

After a number of search results came back with "function unknown", I found this paper: "WHY ARE WAXWINGS "WAXY"? DELAYED PLUMAGE MATURATION IN THE CEDAR WAXWING"

D. JAMES MOUNTJOY • AND RALEIGH J. ROBERTSON Auk, Vol. 105 Jan. 1988 The paper goes over a number of theories, and what their test results show in relation to these theories.

There are some conclusions, but the authors indicate that further studies would help clarify. Some interesting points: 1) Both males and females have the wax, so using the wax as a basis for

mate selection *based on sex* isn't valid. 2) Waxwings are not born with these tips. They develop in size and number over time, so can indicate the age of a bird. 3) Since Waxwings generally

flock together mate selection using territorial competition isn't much of a factor. 4) In their study, mating couples were composed of pairs with the same number of wax tips. Younger birds (wax

tips under a certain number) tended to pair; as those older (wax tips over a certain number) tended to pair. 5) Older pairs = larger birds. The older pairs nested earlier and fledged earlier than

the younger pairs. The older pairs ("alpha pairs" in the study) had higher breeding success than the other pairs. So, one conclusion was that Waxwings could use the red tip colors for mate

selection based on age.

The first 7 images here are a burst of photos I caught of one of the Waxwings taking off.

Red tips on display from below! Red tips on display on folded wings

I also found this paper: "PHYSIOLOGICAL BASIS AND ECOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES OF SUGAR PREFERENCES IN CEDAR WAXWINGS" Martinez del Rio, Karasov, Levey

The Auk 106 January 1989 I just thought this an interesting description of the species:

"We studied the sugar preferences of the Cedar Waxwing ( Bornbycilla cedrorum) , one of the most heavily frugivorous birds in temperate North America (Martin et al. 1951), and analyzed

the influence of taste and postingestional factors on these preferences." This study indicates that Waxwings can distinguish sweet from non-sweet; and also possibly and tell sugars apart.

This might be why they pick up some of the Privet berries and drop them in some of the video clips. They're testing for sweetness. Here's a link to that video again(mp4).

12/25/2020 Another visit to Fiorenza Park. Today, I noticed this Belted Kingfisher (Ceryle alcyon) hunting from one of the trees near the low bridge. I usually don't get a chance to capture video

of one as it hunts, but I was able to catch a couple of clips before the Kingfisher flew off. I got one dive cycle at 60fps; and part of another cycle at 480fps. The series of images below are frame

grabs from the video I edited together from the clips (mp4). Watch the video to see the breakdown.

Belted Kingfisher (Ceryle alcyon) watching Free-falling like a bullet after the glide. Just before hitting the water--beak is slightly open.

Contact! Hitting the water---. --the wings opened. For braking, to prevent diving to deep? As the water settles, Kinfisher's head popped up

Kingfisher pops out of the water! How did it move? As the bird left the water, the wings were folded... ...and the wings were pulled over the back, for first pump.

Wings open and extend to start the first downbeat Downbeat continued, and the Kingfisher continued rising. On completed downstroke, wings are folded for upsweep

12/29/2019 I was able to capture some high-speed video of one of the Vermilion Flycatchers (Pyrocephalus rubinus) that have been staying at the park over the winter.

I still haven't been able to get very close, but I could crop the video into something useable. I've been taking some time to study how birds use their wings--as I've been inspired by

what the high-speed video clips reveal. The report which I've found most useful is this: Aerodynamics of bird flight by Rudolf Dvor�k 2016 (link here). Most of the following comments are inspired

by that report. Many of us have learned that birds' wings are airfoils. In fact, the shape of bird wings is what guided humans to shape the wings on airplanes. Although the airfoil curves of

the birds' wings help it to fly, the biggest factors making their flight possible is that those wings are flexible; and that they move. If we look at the images below-frame grabs from

the cropped video, we can see some of these factors at work. The first group of images show the take off into accelerating flight. At the end of this phase, the flycatcher pulled in

its wings and made a "teardrop shape" of its entire body! This streamlined it for even more brief acceleration.

Feathers "closed" wings extended for lift and thrust. For lifting, wing tips fold in, feathers "open" to let air through. Wings at full lift, they're extended for next down stroke.

Next downstroke, with slight tilt--low leading edge. Pushing down generates forward thrust, and increases lift from wings. Bring the wings all the way down for full propulsion.

The vermilion also landed back on the same twig, and I caught that too. We can look at the images below to see how the wings were used a bit differently to slow the bird . Many of the

movements look the same(after all it's the same wings doing the movements) , but there are subtle differences. . Most of the following comments areinspired by Aerodynamics of bird flight by

Rudolf Dvor�k 2016. (link here)

The braking maneuvers stopped all the forward momentum of the flycather, allowing it to land gently on the tip of a twig. Again...here is the link to that video.

Most feathers "closed", wings extended for braking. For lifting, wing tips fold in, feathers "open to let air through. Wings at full folded (bent?) position.

With wings bent, they are lifted above the back . Opened and Pushing down for more braking. Notice open feathers at wing tips, allowing air to pass through there.

02/03/2019 I watched some Swamp Sparrows (Melospiza georgiana) foraging at BBSP. I shot a few pictures, and I noticed that did an odd "skip" step from time to time. I decided to shoot some

high framerate video so I could see what the Sparrows were doing. I found references to Sparrows doing a "double-scratch" behavior as they look for food. My first reference, Sibley Guide to Bird

Life and Behavior (page 524) gave an interesting description on how the "double-scratch" was performed. However, when I watched my footage, which enabled a 16x slower view, I saw that

something different was going on (if the Sparrows were doing the "double scratch). The series of images below show a single instance of this behavior, and the anigif at the end shows the series

together.

This movement started by a slight dip as the Sparrow set its legs and grabs with its toes, then a quick push to the rear. Once the bird is moving backwards, it then pulls its legs back towards the

body. Since the Sparrow is moving backwards this adds force to the 17-gram mass of the Sparrow's body. This jerks whatever the Sparrow has grabbed backwards. Momentum expended, the

Sparrow ends up near to, and a little behind of, where it had started. Then, it looks down to see what it might have uncovered. After a brief search, the Sparrow grabs whatever it finds with its beak,

moves on, or clutches another clump and pulls again. The images below are frame grabs from this video clip, the video was shot at 60 fps and at 480fps.

As I inspected this, I began thinking about how few animal species are "obligate" bipeds. That is, animals that have adapted to that they primarily walk on two legs...because that is the only way they

can walk efficiently. It appears that only birds and...humans are bipedal by nature; although there are a few exceptions among other species. But birds only have two legs that they can use for

walking...and for grasping. Their two front limbs has lost almost all ability for grasping or manipulating because they have become wings.

( I say "almost all" because there are always exceptions I don't know about.) So, prey and object manipulation is either done with their beaks, or, with their feet--or by a combination of both.

I thought pulling up material by grasping with both feet and then jerking backwards with their body is quite amazing because of the complex physical coordination it requires.

They are yanking backwards with both feet-without using their wings at all-and they aren't bracing against anything to apply force, And...they don't fall down!

After I wrote that last two sentences, I started thinking about the movements that the Sparrow had done, and I thought that I would try to do them myself. So, I designed a simple experiment where I would

try to move an obstacle that was covering food by using my feet and the body movements performed by the Sparrow. I filmed this experiment, and I believe that I successfully copied what the Sparrow

had done. The video clips showing my experiment can be seen here.

Grabs with toes, and sinks just a little bit.....

Pushes backwards and fully extends the legs as body moves back.....

Pulls the legs and feet in, which brakes the body mass, but also pulls at the substrate grabbed by the toes; stops going backwards, then lean forward....

Look around to see if any morsels were uncovered, then maybe a half-step to grab again.....

11/18/2018 Quick 480fps video clip of a Blue-Winged Teal doing a vertical takeoff from water (slowed 8x). Blue-winged Teal taking off in slowmo

04/08/2018 The weather had gotten cool, and as the air warmed, flocks of Swallows began flying. I found myself in the midst of them. So, I filmed some video. Video clip is here. A framegrab

from the video is below.

09/16/2017 and 10/08/2017 I helped a friend repair some damage in the emu pen, and shot a few video clips. The links are here (maybe I'll post some frames here).

Emu walking filmed at 120fps wmv 10/08/2017

Minor repair of shelter with emus vid mp4 09/16/2017

01/08/2017 Today, I was able to capture some high-speed video (480 fps) of some Blue Gray Gnatcatchers (polioptila caerulea) as they foraged among the trees. According to The Sibley Guide of

Bird Behavior, these birds eat small insects and spiders. Sometimes, they open their tails to expose the white feathers, and flick the tail upwards--possibly to scare prey out

so they can catch it. I don't see this behavior in these two clips. In the first clip, the gnatcatcher appears to pick something off the underside of a branch. In the second clip, the gnatcatcher is

hovering in front of a bunch hanging dead leaves. Then it turns its head sideways to focus an eye inside the leaf, then takes off.

This bird *does* open its tail, but it appears to me to be using it to stablize flight. I'm impressed by the number of times the birds pull in their wings and are briefly suspended,

in a "free-fall" situation. The edited video clip is here. The three images below are frame-grabs from the video.

02/06/2010 Today I caught this high-speed video clip of an Eastern Bluebird grabbing a seed. It's a bit out of focus, but still fun to look at.

The image below is a screengrab from this video clip.

01/10/2010 Today was the first bright, sunny Sunday we've had in almost a month. I didn't spend as much time out around the bigger lakes as I'd like, but

We had really cold weather recently. I got to the park a little late Sunday 01/10/2010--but I was a bit sick. I headed straight to the North tip of Elm Lake (near Horseshoe Lake ). An otter had been

seen there last week, and I hoped to get lucky. I also wanted to see how much ice there was, and see how the birds were reacting to it. It was fun watching some of the Moorhens trying to walk on

the ice...and breaking through (without harm--they float). Today's RICKUBISCAM shows one of the Moorhens on the ice. This video clip shot at high speed (wmv 12.3 mb) shows one Moorhen

gingerly walking on the ice (but remember this is slow motion video). If I wasn't already sick, I'd have gone to 40 Acre Lake to see more of the birds on ice. Lakes freezing over is an uncommon

occurrance in this part of Texas.

I had no luck on the otter, but I got to spend some time with the Vermilion Flycatcher that's been making its rounds at that part of the lake.. It made a number of appearances and flybys. Of course,

that early in the morning, if it went east it was directly in the sun. If it went north, I'd face into the sub-freezing wind and my eyes filled with tears and blinded me. (ha!) However, I did get a little clip

of it working. The image below is a frame capture from the video clip. And here's a link to the video clip (wmv 5.0 mb).

---------------------------------------

----

----

------------------------------------- ----------------------------- - Immature Bald Eagle?---------------------------------

A bit later, as I was looking South (towards the water station), I saw the small group of Whistling Ducks take off and fly towards me. None of the other waterfowl took off. When I looked up, a rather

large bird was flying towards me, following the trail. It flew directly over me, and as I looked up it looked very odd. The color seemed to be overall dark brown, with lighter dapples in it. I figured it was

something uncommon--but also thought it might be an immature version of whatever bird it was (as a non-birder, it just seems that as they grow up they go through some weird color phases. I thought

it could possibly be a Bald Eagle.). As I picked up my camera to get a shot, I turned and faced straight up, right into the wind--and my eyes teared up and I was blinded....

The bird began circling, and so as it passed in wide circles and went off to the west, I was finally able to snap a couple images, the picture above is the clearest one. Sorry I couldn't get better images.

Can anyone verify what this is?

And it was really sad to hear about one of our Least Grebes. It evidently had gotten lost under the ice while diving, and drowned. The carcass was salvaged from the ice and will be used for intrepretation.

Since then, I've heard that none of the Least Grebes have been seen in the park since this freeze. I prefer to think that they flew off, instead of thinking that they all died.

Later in the day, I went over to Creekfield Lake. Right near the footbridge there were some birds looking for food. One of them was a Ruby-Crowned Kinglet. It flew close by, so I was able to shoot some

high-speed video (for slow motion) clips of it hunting. The image below is a frame capture from the video, and here is a link to the video clip (wmv 14.0 mb).

----------------------------------------------

-

- 08/16/2009 & 09/06/2009- I got most of the information that follows from The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior 1st Edition pp 357-360. Hummingbirds are related to the birds known as Swifts.

At this time of year they are migrating South, and so large numbers of them are seen as they try to store fat for their trip. Although related to the Swifts, Hummingbirds are different from other birds in

many ways. The unique way that they move their wings allows them to hover in any direction; and even fly upside-down. This adaptation makes it possible for them to hover, and feed on plant nectar.

Hummingbirds normally keep their body temperature similar to that of other birds--104-111 degrees F. But if food is scarce, or if the temperature drops they can enter a "state of torpor"--a sort of

suspended animation (reptiles can do this also--but they are poikilothermic ("cold-blooded")--so have no internal control of their body temperature). In this torpid state, Hummingbirds can lower their body

temperature to 55 degrees F or less to conserve energy. While in this condition, they can lower their heart rate to 50 times per minute. Compare that to their normal rate of 250 beats per minute when at

normal rest, or 1250 beats per minute while flying and looking for food!

Besides eating nectar, Hummingbirds also eat insects and other small prey. They actively hunt for these items, even using techniques that other birds use, such as "hawking"--launching from a perch to hit

passing prey, or hovering and then diving repeatedly into a swarm of insects; "gleaning"--searching at the tips of leaves and tiny openings in bark for tiny larvae, or hovering over leaves and litter and using

the air wash to turn them over, or even "poaching"--where they steal food from other hunters--such as spiders. They sometimes even eat the spiders. This "poaching" ; or the fact that they use spider

webbing while constructing their nests, may explain how Hummingbirds sometimes get trapped in spider webs. The two images at the feeder below (HUMMINGBIRD EATING--WINGS UP, BACK) are

cropped from photos I shot (as is today's RICKUBISCAM). The other two images belows (HUMMINGBIRD 08/16 AND 09/06) are frame captures from video clips that I shot. The links for the clips are below

those images. Shooting at high-frame rate video captures the grace and perfect control the Hummingbird has as it flies. A really good example of this is shown at the end of the 09/06 clip where the

Hummingbird shakes itself while it's hovering--and it stays in complete control. The 09/06 clip also features the Hummingbird taking off and landing.

-

-

HUMMINGBIRD EATING--WINGS UP HUMMINGBIRD EATING--WINGS BACK HUMMINGBIRD 08/16/2009 -HUMMINGBIRD 09/06/2009.

Hummingbird 08/16/09 210&420fps wmv 11.6mb Hummingbird 09/06/09 30&210fps wmv 12.1mb

The Hummingbird's tongue is long, thin, and forked at the very end. It also has two lengthwise, tiny grooves which conduct the liquid into the hummingbirds throat by using the passive means of capillary action,

instead of requiring effort to "suck" the nectar. The image below of the Humminbird showing its tongue is cropped from a photo of mine. (See HUMMINGBIRD TONGUE, below.) I have read that Hummingirds

will favor red flowers or objects--but as the 09/06 clip shows, this isn't absolutely necessary. The flowers in that clip are yellow; and they are about 15 steps away from the Hummingbird plants in the 08/16 clip.

-

-

HUMMINGBIRD TONGUE RICKUBISCAM 09/12/09

Something interesting that I've come to realize (and one which would probably upset many uninformed folks) is that at this time of year (late summer/early fall) some our arthropod species (including insects and

spiders) are nearing the end of their adult lives and are at their largest. Many people have heard of "bird eating spiders" (spiders that eat birds) and when they hear the term, they think of the large Tarantula-type

species that live in other countries. However, we have bird-eating spiders here, too. That is, if you count Hummingbirds. Two of our large spiders--the Black and Yellow Argiope (Argiope Aurantia), and the

Golden Orb Weaver (Nephila Clavipes) spin orb webs big enough and strong enough to catch Hummingbirds. I've had correspondence with someone in College Station who has pictures of a Argiope eating a

Hummingbird caught in a web outside her house. She saw another Hummer caught at a another time, but was able to free it.

Another arthropod that has been photographed eating Humminbirds is the Praying Mantis. From time to time there have been images of Hummingbirds in the clutches of a Mantids on the internet. The first time

*I* saw such a picture was in an old issue of Texas Parks and Wildlife magazine--in the rear "Parting Shot" section. So, rather sad news. It's kind of interesting that both arthropods are usually considered

beneficial (except to arachnophobes perhaps; and some people think mantids are creepy); but their popularity shrinks immensely in a case like this. For me, this just illustrates some of the complex relationships

between predators and prey in nature. Now I want to see if I can film a Hummingbird hunting.

01/25/2009-- While the weather is cold, I've noticed small birds making short flights over the water, hovering a bit and doing these quick acrobatic maneuvers. I guessed that they were snatching small insects

out of the air. I wanted to try to catch some of this intricate flying on film, but the birds move so quickly that it's hard to track them. I decided to try for some high framerate video. I caught a Yellow-Rumped Warbler

doing some hovering and low flying. I believe that the hovering either flushes insects or allows the Warbler to locate some. According to The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior the Warblers are generally

insectivorous, including the Yellow-Rumped Warbler. However, over the winter "in the East", Yellow-Rumped Warblers will eat berries and other fruits. (Pages 499-500). I shot some slow-motion video of one of

the Yellow-Rumped Warblers hovering. It appeared to hover mostly over patches of floating weed. See LOW FLIGHT below. The video clip is here (wmv 3.5 mb).

----------------------

LOW FLIGHT

5/07/2006--There is a radio repeater post right next to the VC/NC (Visitor Center) at Brazos Bend State Park. It is taller than the top of the two-story VC/NC. Not long after it was erected, woodpeckers began nesting

in it. The image below (WHO'S THERE?) is the face of a Pileated Woodpecker that was working on a nest inside the post. While normally somewhat shy, the woodpeckers in the post can be observed from a relatively

close distance, if the observer stays quiet and moves slowly. In fact, it is possible to put your ear against the post and hear the woopecker knocking away inside. For the photo I used for the RICKUBSCAM shot, I

moved close to the post while the woodpecker was inside, then leaned against it and shot up at the hole. There are more pictures below that will help to put things in perspective. The post is perhaps 50' high. You can

see that, even with the foreshortening effect, the top end of the post is not that far from the woodpecker. The "moving back" effect is only different cropped sections of the same image.

-

- -

- -

-

WHO'S THERE? A LITTLE FURTHER BACK EVEN FURTHER BACK

-

-

- -

- --

--ARE YOU WATCHING ME? FROM THE SIDE FROM THE SIDE, CLOSER

According to The Encyclopedia of North American Birds by Michael Vanner (Parragon Publishing, 2003 edition), The Pileated Woodpecker (dryocopus pileatus) is the largest North American woodpecker (after the

Ivory Billed, which is considered extinct--although recent findings may prove it still survives!). This book also says that the staple diet of these woodpeckers is carpenter ants, but it will also eat various other

wood-boring insects, or even berries.

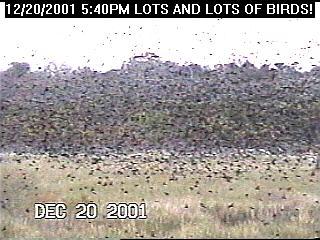

December 20, 2001 At Brazos Bend Park, at around 5:30 or so in the evening (or just before darkness falls), if you happen to be standing on the observation tower which overlooks Pilant Lake, stop whatever you are

doing, listen, and look. You will not be disappointed (BIRDS! , below) On that particular evening, the first sign of what was coming was the crows--a rising racket of raucus cawing which got stronger and stronger until

it just suddenly cut off. It was as if someone had hit a switch. That was in the trees off to the east. Then, off in that direction, I could see a faint smudge that slowly moved across the sky. It got thicker and closer, and then,

when I looked at it through binoculars, I saw that it was a huge mass of birds. Click here for a short clip showing this mass in action.. (flv video 564kb no sound)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------- BIRDS!

Go back to my home page, Welcome to rickubis.com

Go back to the RICKUBISCAM page.

Go back to the See the World page.