Amphibians

This

page was born 12/02/2009. Rickubis designed it.

(such as it

is.) Last update: 3/25/2024

Images

and contents on this page copyright ©2002-2024 Richard M. Dashnau

Update 03/19/2024 - 03/10/2024

Brazos Bend State Park I was watching various wading

birds in Pilant Slough near the Observation Tower at 40 Acre Lake. They

were

foraging

on the floating plant mats. I like to watch this

behavior to

see what the birds are catching. The birds move quickly, and there are

many of them, so it takes some

luck for me to be watching the right

bird at the right time to see a successful capture of prey.

It

takes even more luck to catch it with a camera. For a long time

(years?) I've

been hoping to film the capture of one specific

animal--and today I was successful! The pictures on not very

good, but they are still clear enough for me to identify the

prey. The Great Blue Heron, Ardea

herodias

was at least 25 yards away, and I shot a burst of photos when it

grabbed something. I couldn't identify the prey until I got

home

and examined the photos. The images below were taken as a single burst

of photos (at 10 images per second); so the prey was gone in less than

a second.

What was it? The Great Blue Heron had caught and eaten an

Eastern Newt, Notophthalmus

viridescens. I've known the newts live here.

We've caught them during our

Pond Life Programs.

While

growing up in the Northeast U.S., I'd found the newts many times, and

had kept them briefly. I'd also found Red Efts up there, and in that

environment I'd found them

nearly the size of adult newts, and VERY

bright orange. I had learned that the Eft stage was toxic,

and

the orange was a "warning" color (this is called "aposematic"

coloration).

Here's an study:

"Chemical Defense of the Eastern

Newt (Notophthalmus viridescens): Variation in Efficiency against

Different Consumers and in Different Habitats" by Zachary H. Marion,

Mark E. Hay.

If you'd like to read it, here's an open-source link(my favorite

kind): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3229496/

From this study (notes in [[double

brackets]] are just my own comments):

1) "Like Taricha newts, the eastern newt (Notophthalmus viridescens)

is assumed to deter predators by secreting TTX, with all life-history

stages reportedly unpalatable to a variety of vertebrate

and invertebrate predators. " [[ TTX=tetrodotoxin. They

are toxic at *all* stages!?!? ]]

2) "The lack of rigorous research on the chemically-mediated

predator-prey interactions involving Notophthalmus viridescens

is surprising given that eastern newts are thought of as keystone

predators

that regulate the diversity and abundance of larval anurans, aquatic

invertebrates, and the ecosystem functions of some freshwater

environments." [[

*Keystone predators*!? This little

amphibian? What a

great example of how much a single organism can affect pond life. ]]

3) "The eastern newt (Notophthalmus

viridescens Rafinesque, Salamandridae) is one of the most

widely distributed salamanders in North America and occupies lentic

environments

across the spectrum from temporary to permanent water

bodies." [[

Where I come from, I knew them as "Red-Spotted Newt", but they're the

same species. ]]

4) " Notophthalmus

viridescens

secrete tetrodotoxin (TTX) which could serve as a chemical defense

against predators. Concentrations of TTX are greatest in the red eft

stage,

followed by adults, eggs, and finally larvae." [[ As stated above, TTX is

in all stages, although greatest in the red eft stage (which has the

warning colors). ]]

5) " To assess newt palatability to co-occurring consumers, we used

adult largemouth bass (Micropterus

salmoides; 15–20 cm standard length [SL]), juvenile

bluegill sunfish (Lepomis

macrochirus; 2–4 cm

SL), the crayfish Procambarus

clarkii (9–12 cm total length), and adult bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus;

12.5–18 cm snout-vent length)." [[ The list of predators

that they used are all inhabitants at BBSP also.

The

crayfish is our big Red Swamp Crawfish. It is native here, and the same

species that is cultivated and served in restaurants. ]]

6)

"Here we show that eastern newts, their early ontogeny, and especially

their dorsal skin areas are distasteful to common aquatic consumers

such as fish and crayfish, that fish avoid newts due

to

chemical deterrents, and that the compound TTX can produce this

response at small portions of its reported natural concentrations. Yet

some consumers, such as bullfrogs and possibly

other reptiles and

amphibians, appear undeterred by TTX." (page 6)

7) "Our results show that the newt Notophthalmus

viridescens

is unpalatable to fishes and a crayfish, and that this unpalatability

is chemical in nature, is concentrated in exterior dorsal skin, and is

likely

due to TTX or related secondary metabolites. However, this chemical

defense is ineffective against bullfrogs (and possibly turtles),

allowing considerable consumption of tethered newts in

the field." (page 7)

From

my observation here, I can add Great Blue Herons to the list of

predators that eat Newts. The last two images below show that

the

Newt was swallowed (its head is

visible in image #3), and it was

gone after image #4 and the images that followed (not shown here).

It does make me wonder if the TTX has any effect on the

Herons

after

they've eaten a newt. I have seen other wading birds catch newts but it

has been a very rare observation, and I have never been able to capture

it on film before.

Here's an Eastern Newt, Notophthalmus viridescens, that we caught at during a Pond Life Program a few weeks later, on 03/24/2024 .

01/30/2022 Speaking

of Sirens (Lesser Siren-Siren intermedia)--I spent some hours near the

mother alligator and her den. While I was there, I discovered

a

partially-eaten carcass of a Siren.

I don't know how it got there,

but it was an interesting interpretive subject of a few minutes.

Then I had to wash the slime and other fluids off my hands.

Fortunately I always have a bottle of hand

disinfectant with me--and

one of the visitors also gave me a wet wipe, so I could handle my

camera without getting it covered with slime.

I

usually only see Sirens when one of the wading birds has caught

one. Wading birds (Herons, Egrets, Bitterns) do not usually

break

their prey into small pieces, or bite off parts. Sometimes

they

may discard spines or legs. So, I didn't think that one of those had

partially-eaten the siren. But something (such as a Caracara) could

have stolen the Siren from a wading bird. Anyway,

I could use the

carcass to point out the unique features on this amphibian. The two

front legs with visible toes are distinct. The external gills are also

visible, though not quite as clear, lying

against the skin just above the front legs. I put the carcass back in

the grass where it had been found.

07/19/2021- I

haven't been able to exercise in the area I normally use because it's

been raining. Today, it seemed like the circle had dried

enough

to use,

so I walked around it, clearing sticks and other items.

As I made another circuit, I noticed a round hole.

It was

about 1.5 inches (3.8 cm)across. It was much

too large to be a

cicada exit burrow. My first thought was that it had been a crawfish

burrow (Red Swamp Crawfish Procambarus clarkii) that had had

the

"chimney"

knocked off--perhaps by park mowers. I wasn't wearing my

glasses,

but as I stood above the hole and looked down, I thought there was

something

in there. I retrieved my glasses and a camera from my car,

and returned.

I

stood above the hole, this time wearing my glasses. I bent

and

looked down into it...and something moved. Then, a face

appeared

at the opening! It was a toad!

The little face looked up at me. I'm pretty sure that the

toad made that hole--probably as the water dried and of

course before the mud had hardened. I took

a few more pictures--giving the toad space so I didn't scare it.

Then, I moved my workout to the next tree over. In

the cropped images, I can see a blister at the front

edge of its mouth.

It looks a lot like fire ant blisters I've gotten. Poor little critter.

I've tried to figure out what kind of toad it is.

After

some searching, I've found that it's

probably a Gulf Coast Toad

(aka Coastal Plains Toad; Incilius nebulifer). I can't see the toad's

body, but those prominent bone crests between the eyes seem to be a

defining feature. I found the information in this: A review of the

biology and literature of the Gulf Coast Toad (Incilius nebulifer),

native to Mexico and the United States

by Mendelson, Kinsey et. al.

(Article in Zootaxa � June 2015 DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3974.4.4)

(update 07/20/2021)- I returned the next

day--after all, it's where I regularly practice. I was sad

and a bit relieved to see that the

toad

had left. Relieved, because I thought that the toad was at

risk,

even in the hole. Since the toad had gone, I could examine the hole.

From

the top, the hole is about 3cm across (1.2 inches--I'd estimated 1.5

inches). I tried for pictures into the hole. It does have a

visible

bottom. That "ledge" is probably just a hard area in the

substrate that couldn't be burrowed through.

I

was able to see a bit more clearly into the hole than the images show.

So I thought it would be ok to probe a bit with my finger. The mud was

packed, not soft. Also, the narrow

parts are like shelves--that

is, the wall is the same width under it as over it. I

couldn't

tell for sure if the bumps were exposed tree roots. Also, the hole

stops at the bottom, and

does not turn in any direction into

anything horizontal. Finally, I made a "high-tech depth sounding

device" from a twig and placed it into the hole. I pinched it at the

top edge of

the hole, and then-holding by the pinched point-placed

it onto my gauge to get a depth reading. The hole is about 5

inches (13 cm) deep.

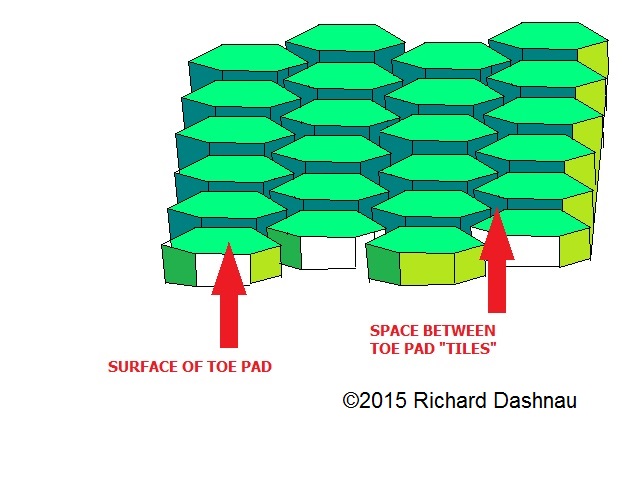

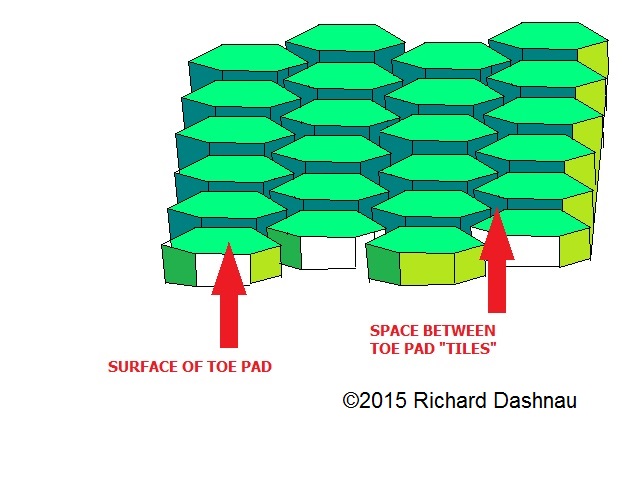

04/09/2009

--I encountered a Squirrel Tree Frog and was able to shoot

some

high-speed video of it as it climbed a tree. While watching the video,

I noticed how the frog occasionally was able

to hold on by just one

front foot. Then I wondered how the frog's foot stuck at all. I was

pretty sure that it was by suction (even though the toe pads look like

suction cups--see below). I searched

online and discovered that

the surface of a tree-frog's toe pads is not smooth. Instead, the

surface is split into many microscopic "tiles". These

sections

are each surrounded by a narrow space.

Mucous is extruded from the

spaces between these "tiles" or "pegs". The mucous wets the

face

of each "tile", which then sticks to a surface by liquid adhesion

(similar to the way a beer glass

can stick to a coaster). The

adhesion of thousands of these microscopic "beer glass bottoms" combine

to form a powerful sticking force. When the frog

moves, it

has to peel its toes off the

surface it is clinging to.

SQUIRREL

TREE FROG CLIMBING (Link to video (wmv))

I found information about this in these papers (I haven't put

links, since they usually expire over time):

ADHESION

AND DETACHMENT OF THE TOE PADS OF TREE FROGS

BY GAVIN HANNA AND W. JON P. BARNES*

1990

The

SEM Comparative Study on Toe Pads among 11 Species of Tree Frogs from

Taiwan

Wen-Jay Lee, Chia-Hua Lue, Kuang-Yang Lue

2001

Wet

but not slippery: boundary friction in tree frog adhesive toe pads

W

Federle, W.J.P Barnes, W Baumgartner, P Drechsler and J.M Smith

J.

R. Soc. Interface 2006 3, 689-697

doi:

10.1098/rsif.2006.0135

2006

October

17, 2004The

image below (GREEN RIDER) shows a little green hitchhiker that landed

on

the argo while I was mashing more rice Sunday.

-------------------------------

GREEN

RIDER

Actually,

I see these Green Tree Frogs fairly often while in the rice, and

usually

that just land on the argo, or me, and then just jump off. This one,

however,

stayed for a while, and so I grabbed

my "smaller" camera and took some

pictures. They came out really well, I thought, so here they

are.

I can't believe they came out like this!

I

was

got this great closeup (see REALLY CLOSE,

below), and while I had the camera

near it, the frog turned and faced the camera (see GET MY BETTER SIDE,

below). Finally this frog jumped off.

-

- -

- -

- -

-

REALLY

CLOSE

GET MY BETTER SIDE

YOU WANT ME TO JUMP!?

WHAT ARE YOU POINTING AT?

DON'T MAKE ME GO

Later

in the afternoon, I was at it again with the argo, and another frog

jumped

on. This time, I reached for it (with the camera in the other hand),

and

the frog jumped onto my hand. It crawled to

the knuckle of my curled finger,

and posed for a while (see YOU WANT ME TO JUMP. above). After I took a

few pictures, I gently tried to let it jump off, but it wouldn't go. I

extended my finger

(see WHAT ARE YOU POINTING AT, above), and the frog

just crawled around on my hand and finger. It perched on my

knuckle

again, where I got this great picture (see DON'T MAKE ME

GO, above).

It always affects me to have such a small creature trust me like this.

I want to stand still for a while and let it remain. But, I had my work

to do, and I figured the frog would be safer

back in the grass, so I finally

got it to jump to a strand. With a slight twinge, I moved away from my

brief acquaintance.

If

you'd like to know more about the park follow these links:

Brazos

Bend State Park

The main page.

Brazos

Bend State Park Volunteer's Page

The

volunteer's main page.

Go back to my home page, Welcome

to rickubis.com

Go

back to the RICKUBISCAM

page.

Go

back to the See

the World

page.